China’s President Xi Jinping presided over the country’s National Day, marking 70 years of Communist Party rule. The military parade included 15,000 personnel, 160 aircraft, and hundreds of weapons—some new—in a projection of the country’s power under Xi, who delivered a speech with thinly veiled threats toward Hong Kong, Foreign Policy’s Aubrey Wilson writes.

“No force can shake the status of our great motherland, no force can obstruct the advance of the Chinese people and Chinese nation,” he said, adding that Beijing would “maintain the lasting prosperity and stability” of Hong Kong and Macau. Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam was pictured smiling among other dignitaries during the parade.

Xi has revived the methods and symbols of Maoism not in service of a return to the past but in order to advance his own transformative agenda, one that seeks to ensure that all political, social, and economic activity within, and increasingly outside of, China serves the interests of the CCP, notes Council on Foreign Relations expert Elizabeth E. Economy, author of The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State.

Xi has revived the methods and symbols of Maoism not in service of a return to the past but in order to advance his own transformative agenda, one that seeks to ensure that all political, social, and economic activity within, and increasingly outside of, China serves the interests of the CCP, notes Council on Foreign Relations expert Elizabeth E. Economy, author of The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State.

He is creating a model that reasserts the power of the Communist Party; progressively erases the distinction between public and private in both the political and economic spheres; and seeks to integrate foreign actors, including private businesses, more deeply into a system of CCP values and institutions. Xi also aspires to accomplish what Mao and his successors could not: to render irrelevant the political and physical boundaries separating Taiwan and Hong Kong from the mainland, and to offer China as a legitimate model for other countries disinclined toward liberal democracy, she writes for Foreign Affairs.

And yet…..

“To the Communist party, the events in Hong Kong signal its failure,” says Jean-Philippe Béja, research emeritus professor at the centre for international studies and research at Sciences-Po in Paris. “A generation raised under the red flag not only has not become ‘patriotic’ as it hoped, but has become increasingly estranged from China,” he tells The Guardian:

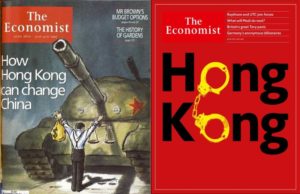

Hongkongers’ frustrations have exploded into three months of street protests that show no sign of abating. Demonstrations have seen riot police firing teargas, rubber bullets, pepper spray and bean bag rounds at protesters who in turn have thrown petrol bombs, vandalized metro stations and set street fires. Some trampled and burned the national flag. Protesters call the movement a revolution to “reclaim” and “liberate” Hong Kong.

“The level of anti-China feelings so candidly expressed is new in Hong Kong. In the past it has been cautious; now the young are much more vocal,” says Jean-Pierre Cabestan, a professor at Hong Kong Baptist University and the author of “China Tomorrow: Democracy or Dictatorship?” “This is seen by China as a direct challenge.”

“The level of anti-China feelings so candidly expressed is new in Hong Kong. In the past it has been cautious; now the young are much more vocal,” says Jean-Pierre Cabestan, a professor at Hong Kong Baptist University and the author of “China Tomorrow: Democracy or Dictatorship?” “This is seen by China as a direct challenge.”

Even private conversations with Chinese scholars and officials revealed a sense of defensiveness and victimhood that is striking for a country as ostensibly secure and successful as China, adds Matthew P. Goodman, senior vice president and Simon Chair in Political Economy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Unprecedented resentment and resistance

After months of large-scale protests in Hong Kong, the city’s future as a bridge between mainland China and the outside world is in serious jeopardy. Fortunately, all sides share an interest in pursuing more inclusive growth within the “one country, two systems” framework that has been critical to Hong Kong’s success, CFR expert A. Michael Spence writes for Project Syndicate.

But CCP control is fueling unprecedented resentment and resistance—and not only in Hong Kong, analyst Jimmy Lai writes for The Wall Street Journal [HT:FDD]l

But CCP control is fueling unprecedented resentment and resistance—and not only in Hong Kong, analyst Jimmy Lai writes for The Wall Street Journal [HT:FDD]l

The China-U.S. trade war is an epochal event that can push China to the brink of collapse, especially if the U.S. links its values and human rights to its dealings with China. If China agrees to the structural changes America demands in this trade war, it will greatly increase China’s cost of doing business. And if Mr. Xi doesn’t agree to these structural changes and a deal with America is killed, the flow of foreign currency into China will slow, delivering a potentially fatal blow to an already weakened economy.

Western observers who remember the violent crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators in Tiananmen Square 30 years ago have been puzzled by Beijing’s forbearance [in Hong Kong]. Some have attributed Beijing’s restraint to a fear of Western condemnation if China uses force. Others have pointed to Beijing’s concern that a crackdown would damage Hong Kong’s role as a financial center for China, notes Andrew J. Nathan, Class of 1919 Professor of Political Science at Columbia University.

National Endowment for Democracy

But according to two Chinese scholars with connections to regime insiders and who requested anonymity to discuss the thinking of Beijing policymakers, China’s response has been rooted not in anxiety but in confidence, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

Beijing is convinced that Hong Kong’s elites and a substantial part of the public do not support the demonstrators and that what truly ails the territory are economic problems rather than political ones—in particular, a combination of stagnant incomes and rising rents. Beijing also believes that, despite the appearance of disorder, its grip on Hong Kong society remains firm. The Chinese Communist Party has long cultivated the territory’s business elites (the so-called tycoons) by offering them favorable economic access to the mainland. The party also maintains a long-standing loyal cadre of underground members in the territory. And China has forged ties with the Hong Kong labor movement and some sections of its criminal underground. Finally, Beijing believes that many ordinary citizens are fearful of change and tired of the disruption caused by the demonstrations.

Beijing therefore thinks that its local allies will stand firm and that the demonstrations will gradually lose public support and eventually die out, says Nathan, co-editor of The Tiananmen Papers and a former National Endowment for Democracy board member.

Beijing therefore thinks that its local allies will stand firm and that the demonstrations will gradually lose public support and eventually die out, says Nathan, co-editor of The Tiananmen Papers and a former National Endowment for Democracy board member.

Yet the behaviour of western governments since the Hong Kong crisis blew up has been servile, argues analyst Simon Tisdall. What this spineless dereliction implies for other, similar pro-democracy movements opposed to authoritarian regimes, such as those in Egypt and Russia, or for China’s persecuted Uighur and Hui Muslim minorities, is gravely dismaying, he writes for The Guardian. In Washington, London and other capitals, it’s plain that money and power speak louder than democratic ideals, broken umbrellas and bloodied heads.

Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement has struck an emotional chord in Taiwan, adds Brendon Hong. Younger people on the island see traces of the Sunflower Student Movement that took place in 2014, as was pointed out by Audrey Tang, who was involved in those days and is now Taiwan’s digital minister and, in her words, the “world’s first anarchist minister,” he writes for The Daily Beast:

That spring, students in Taipei occupied the Legislative and Executive Yuans. As for the older generation, police brutality and the lack of accountability in Hong Kong remind them of Taiwan’s martial law period that lasted for 38 years until 1987, when democratization took root to eventually lead to a democratic presidential election in 1996. Hongkongers and Taiwanese also share an affinity in their struggle for maintaining their identities, ones that are distinct from the homogeneous national character sculpted by the CCP.

That spring, students in Taipei occupied the Legislative and Executive Yuans. As for the older generation, police brutality and the lack of accountability in Hong Kong remind them of Taiwan’s martial law period that lasted for 38 years until 1987, when democratization took root to eventually lead to a democratic presidential election in 1996. Hongkongers and Taiwanese also share an affinity in their struggle for maintaining their identities, ones that are distinct from the homogeneous national character sculpted by the CCP.