How does political polarization affect democracy over the long-term?

How does political polarization affect democracy over the long-term?

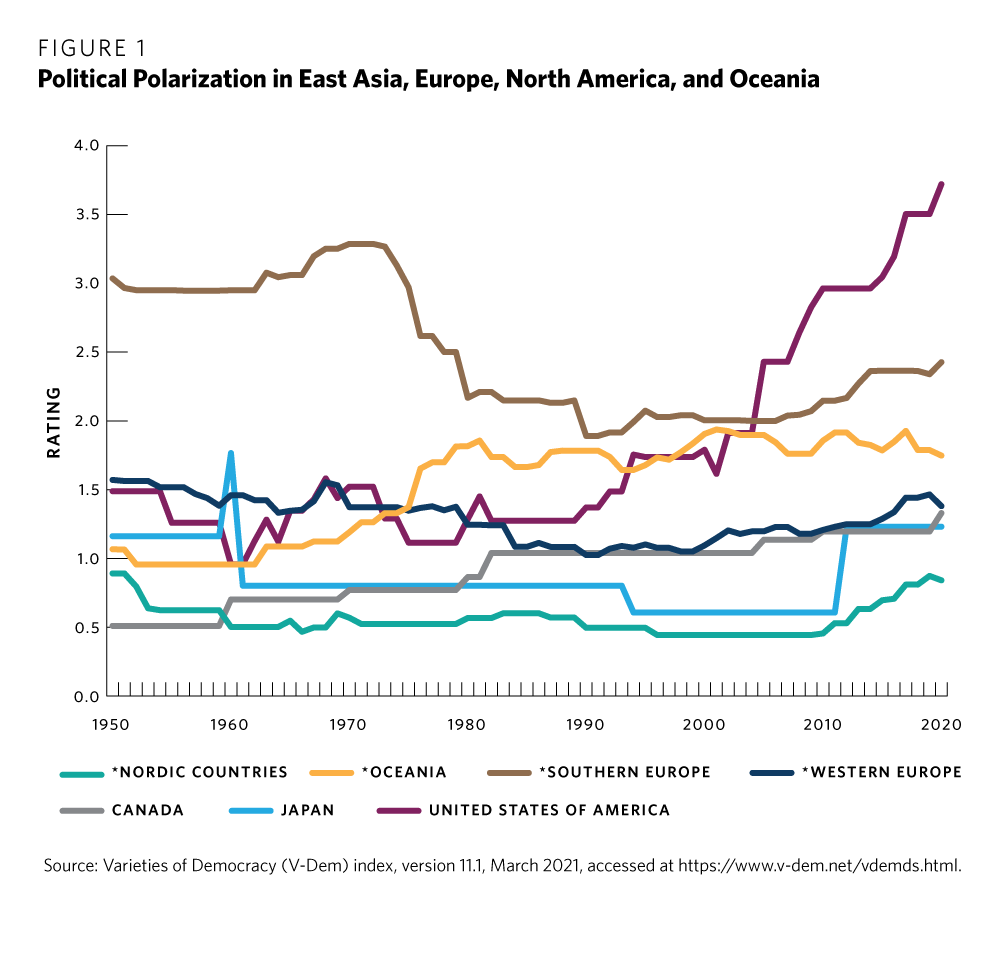

The findings of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) data set are “not encouraging,” say Carnegie analysts Jennifer McCoy and Benjamin Press. Severe polarization correlates with serious democratic decline: of the fifty-two instances where democracies reached pernicious levels of polarization, twenty-six—fully half of the cases—experienced a downgrading of their democratic rating.

This wide assortment of countries illustrates how polarization can contribute to democratic downgrading in multiple ways, McCoy and Press add:

- In some cases, as in Bangladesh in 2002 or Thailand in 2006, polarization—and government dysfunction—became so intense that security forces stepped in and attempted to realign the country’s politics.

- In other cases, like Turkey and Poland, leaders relied on explicitly polarizing populist strategies to gain and retain power, sowing division to energize their supporters while claiming that it is necessary to curtail democracy in order to overcome opponents’ resistance and enact their agenda.

What can be done to stop polarization? M. Steven Fish and Neil A. Abrams ask. Contributors to Democracies Divided: The Global Challenge of Political Polarization, edited by Thomas Carothers and Andrew O’Donohue, suggest reforming the media, political parties, and electoral systems but admit that such measures are extraordinarily difficult to achieve, they observed in a recent issue of the Journal of Democracy. Carothers and O’Donohue also recommend reinforcing guardrail institutions and especially the “rule of law and independent, impartial election administrations”. Yet such measures are scarcely possible while illiberal leaders are commandeering the courts and electoral commissions to consolidate their own power.

What can be done to stop polarization? M. Steven Fish and Neil A. Abrams ask. Contributors to Democracies Divided: The Global Challenge of Political Polarization, edited by Thomas Carothers and Andrew O’Donohue, suggest reforming the media, political parties, and electoral systems but admit that such measures are extraordinarily difficult to achieve, they observed in a recent issue of the Journal of Democracy. Carothers and O’Donohue also recommend reinforcing guardrail institutions and especially the “rule of law and independent, impartial election administrations”. Yet such measures are scarcely possible while illiberal leaders are commandeering the courts and electoral commissions to consolidate their own power.

The V-Dem data show that it is possible for democracies to depolarize, McCoy and Press note. Systemic interventions can help reduce polarization before polarization imperils democracy. Lessons from abroad give us some hints, they suggest:

- Reforms such as shifting to a proportional representation system (as New Zealand did in the 1990s) and/or using ranked choice voting in multimember districts (such as in Ireland) …

- Political parties and cultural influencers need to clearly distance themselves from individuals and groups employing political violence, exclusionary nationalist appeals, or antidemocratic measures, as the Italian parties did to end a decade of violence in the 1970s.

- Elected leaders should listen to legitimate grievances and pursue policies to benefit the whole, not just one party or a small elite. RTWT

Polarization is one of three three causal factors—along with pliable legislatures and piecemeal attacks on institutions – that Stephan Haggard and Robert Kaufman identify in the anatomy of democratic backsliding, drawing on sixteen case studies in the October 2021 issue of the NED’s JOD.

Four basic outcomes are possible from a comparison of episodes since 1950 when a democracy reached pernicious levels of polarization for at least two years,

Four basic outcomes are possible from a comparison of episodes since 1950 when a democracy reached pernicious levels of polarization for at least two years,