Wilson Center

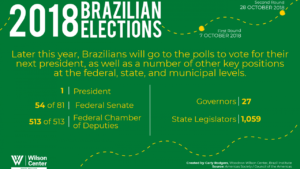

Jair Bolsonaro’s presidential victory in Brazil is part of a growing trend of authoritarian leaders being democratically elected across the world, notes Latin America expert Pablo Galarce.

“[What] has happened today is what happened in the 60s in so many countries where we had military dictators before, and then we had democracy and now, unfortunately, democracy throughout the world has not been able to solve so many problems,” Galarce, a senior adviser at the International Foundation for Electoral Systems, told Hill.TV’s Buck Sexton and Krystal Ball.

“A lot of people [have] come out of poverty, but their issues are still so big, and a lot of people are resorting to violence, to extortion, to narco-trafficking,” he continued. “This is a trend we, unfortunately, see throughout the world.”

Populist leaders are confrontational, mendacious and ruthless — but those who follow them need to have their fears, resentments, and beliefs addressed, if politics is not to descend further, argues John Lloyd, co-founder of the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

America’s Founders worried greatly about the vulnerability of democracy to populist demagogues, The New Yorker’s John Cassidy observes:

America’s Founders worried greatly about the vulnerability of democracy to populist demagogues, The New Yorker’s John Cassidy observes:

In his book “The American Mind,” the historian Henry Steele Commager notes that “the American” of the late nineteenth century had “little time for tradition and authority,” because “he knew that his country had become great by flouting both.” Simultaneously, however, the American “thought his government and the Constitution the best in the world, credited them with a large measure of the success of his experiment, and would not tolerate any attack upon their integrity.”

A sign of a populist leaders’ influence is when he [or she] has “succeeded in creating a daily narrative in which he is the central figure,” Steve Coll, the dean of the Columbia University School of Journalism, told the New York Times.

Accordingly, reporters must adjust themselves to someone who has thrown out the classical rules of debate, said David Zarefsky, professor emeritus at Northwestern University.

Accordingly, reporters must adjust themselves to someone who has thrown out the classical rules of debate, said David Zarefsky, professor emeritus at Northwestern University.

“Logic and argument is built upon a set of assumptions,” he said. “One of those assumptions has to do with the importance of facts and the power of generally accepted beliefs.”

According to the old joke, a liberal is someone who can’t even take their own side in an argument. But it is not so funny now. The foundations of modern liberalism are being challenged aggressively. Western liberals, softened by decades of winning, will have to relearn how to fight, argues Richard V. Reeves, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the author of “John Stuart Mill: Victorian Firebrand” (Atlantic Books, 2007) and “Dream Hoarders” (Brookings Press, 2017).

What can we learn from the liberal lions of the past? Three key lessons stand out, he writes for The Economist:

- First, liberals must fight alongside and for the powerless, the underdogs of both society and economics. ….Today, middle-class and working-class voters and communities are falling further and further behind the upper middle class. Liberals have been too slow to recognise the growing divide, and too afraid to argue for radical solutions, especially in terms of wealth redistribution. This has opened up space for populists.

Second, liberals have to be eternally vigilant against the rigging of markets in favour of vested interests. This is not a battle that will ever end. Those with economic power will always use it to shape market dynamics to suit their own ends. The housing market in America and Britain, for example, is strongly tilted in favour of those with wealth and political power….

Second, liberals have to be eternally vigilant against the rigging of markets in favour of vested interests. This is not a battle that will ever end. Those with economic power will always use it to shape market dynamics to suit their own ends. The housing market in America and Britain, for example, is strongly tilted in favour of those with wealth and political power….- Third, liberals have to sharpen their anti-elite instincts. The emergence of the phrase “liberal elite” is deeply unfortunate, since liberals ought in principle to be wary of the power of elites. But sadly, it applies. Liberals, especially those of an intellectual orientation, have become too respectful of the authority of elite colleges, professional associations, perhaps even of elite publications (like this one). Liberals certainly value expertise. And they worry that mass movements can damage pluralism. Mill and Tocqueville both wrote eloquently on these points. But while elites will always exist, liberals will always fight against them when they become self-serving.

In the latest issue of the National Endowment for Democracy ’s Journal of Democracy, Richard Wike and Janell Fetterolf analyze trends in global public support for liberal democracy—and its rivals, while Christopher Carothers argues that competitive authoritarian regimes have shown themselves to be remarkably unstable.