Twenty years ago, Vladimir Putin appeared on the political Olympus in the guise of an effective bureaucrat with a security services background; a market-oriented statesman and pragmatist without ideological pretenses, notes analyst Kirill Rogov. Today, Putin is a powerful authoritarian leader of the “strongman” type, engaged in a political confrontation with the West and an ideological struggle with global liberalism, in the service of which he is decisively sacrificing any pragmatic goals for developing the country, he writes for The Moscow Times:

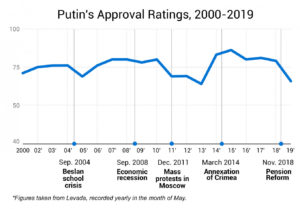

Levada

The total revisionism of the second Putin period is linked to this. The change gave absolute priority to the understanding of ”sovereignty;” searched for new ideological pillars in the form of “social ties” and “traditional values,” pushed aside the imperatives of modernization and formed “nationally oriented elites.” It also refused to recognize the borders that had resulted from the collapse of the U.S.S.R., leading to a decisive turn away from cooperation toward confrontation with the West.

The current Russian leadership might look strong. But it’s actually running scared, Democracy Post’s Christian Caryl adds. As the Carnegie Endowment’s Andrey Pertsev recently noted, “Russians, once cowed by the potential consequences of taking to the streets, are increasingly willing to protest over nonpolitical and local issues.”

Another major protest is planned for Saturday in Moscow. Other gatherings in solidarity are set for various cities across Russia. But the confrontation in the capital is the big event and one that will set the stage for the next act nationwide, The Washington Post reports:

That could be to embolden Putin’s critics after an opposition victory in Russia’s biggest city. Or the Kremlin may end up serving notice to its critics by defeating the Moscow protesters at the hands of baton-wielding police, whose mass sweeps have placed more than 1,500 protesters in temporary detention over the past weeks.

“It’s still a very, very local phenomenon,” said Konstantin Gaaze, an expert at the Carnegie Moscow Center. “But it’s huge, because Moscow is huge.”

“It’s still a very, very local phenomenon,” said Konstantin Gaaze, an expert at the Carnegie Moscow Center. “But it’s huge, because Moscow is huge.”

Analysts say it is unlikely that Russia’s longest-serving leader since Joseph Stalin will give up power completely when his current term ends in 2024, AFP adds.

Political analyst Konstantin Kalachev explained, “Putin’s popularity rating is now completely different from the one he had before. Previously, people truly worshiped him and not just supported him. Today, his popularity is based on the absence of an alternative, on the principle of ‘as long as it is not any worse’.”

Putin faces a conundrum, argues Samuel A. Greene, Reader in Russian Politics and Director of the Russia Institute, King’s College London, and co-author of Putin v. the People: The Perilous Politics of a Divided Russia.

On the one hand, the immediate demands of political survival – from keeping fence-sitters out of the ranks of the opposition, to staving off challenges from a nervous elite – require him to demonstrate that he’s unafraid to use force against his own citizens, says Greene, author of Moscow in Movement: Power and Opposition in Putin’s Russia. On the other, because violence serves to galvanise the opposition, those very demonstrations increase the risk of a revolutionary spiral of escalation.

There is a major reasons why the current protests are different from previous unrest, observers suggest.

“In 2012 the authorities were able to split the opposition from the rest of the population,” said Aleksei Mazur, a political commentator in Novosibirsk. “This time we haven’t seen that yet.”

Two scenarios

“What strikes observers is the culture of public action that has emerged in Russia during the past several years,” a Kennan Institute analyst notes. “A common feature of all kinds of protests—those against hazardous landfills near cities, against construction in public spaces, or for access to elections—is the absence of violence. Most of the demonstrations these days do not have clear leaders, yet they are self-disciplined, calm, and goal-oriented,” writes Maxim Trudolyubov.

“What strikes observers is the culture of public action that has emerged in Russia during the past several years,” a Kennan Institute analyst notes. “A common feature of all kinds of protests—those against hazardous landfills near cities, against construction in public spaces, or for access to elections—is the absence of violence. Most of the demonstrations these days do not have clear leaders, yet they are self-disciplined, calm, and goal-oriented,” writes Maxim Trudolyubov.

What will happen next is anybody’s guess, but there seem to be at least two scenarios, analyst Roman Dobrokhotov argues. Either the Kremlin will be able to put down the protests by force and the Russian public will eventually slip back into its political lethargy, or the situation will escalate, especially if opposition leader Alexei Navalny is sentenced to jail, and protests will spread outside Moscow to the country’s various regions, he writes:

If the second scenario plays out, Putin, whose political philosophy for the past 20 years has been to never make any concessions, would have only one way out: To call a national emergency and unleash a nation-wide campaign of repression, arresting thousands of people, including journalists, human rights activists, lawyers and NGO workers – a crackdown similar to the one in Turkey after the 2016 attempted coup.

“What we are seeing today is the process of struggle, with the underdog maturing and getting stronger by day. At this particular stage, the Kremlin has ‘succeeded’ in what generations of opposition leaders failed to do – it united the liberal opposition,” according to Leonid Ragozin (@leonidragozin), a well-known Russian journalist. “This ain’t going to be a linear process, but unless Putin starts reforms (as in real clampdown on corruption and criminal behaviour of Security bodies) the intensity of this struggle will keep rising.”