Credit: Badiucao

This week, a major university in D.C. found itself in the position of censoring criticism of the Chinese government by removing art posters highlighting Beijing’s human rights abuses during the first week of the Winter Olympics. It’s not the first time China’s long arm of influence reached onto U.S. campuses — and it won’t be the last, The Washington Post’s Josh Rogin writes:

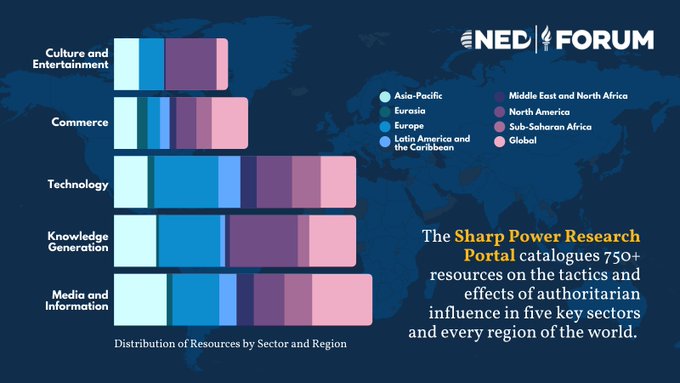

On Monday, George Washington University President Mark Wrighton was compelled to issue a public statement to all members of the university community admitting he had been wrong to remove posters displayed on campus that protested the Chinese government’s persecution of Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Hong Kongers as well as Beijing’s handling of the covid-19 pandemic. In so doing, he had initially followed the lead of Chinese student organizations who complained about the posters….. Universities in free and open societies must set up clear standards and processes for building resilience to what NED call’s China’s “sharp power” tactics, said Christopher Walker, vice president at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). That work has to be done before, not after, the pressure comes from the Chinese Communist Party, its proxies or other authoritarian forces.

“Given the extent to which these problematic intrusions already have come into view, there’s a persistent lack of preparation among universities and the knowledge sector more broadly to ensure that essential standards of academic freedom are upheld,” Walker added.

European researchers with the Partnership for Countering Influence Operations (PCIO) characterize Chinese-state-run influence operations as just one component of a complex information environment where disinformation mixes freely from a variety of sources, add Carnegie analysts Carissa Goodwin and Dean Jackson, project manager of the Influence Operations Researchers’ Guild.

As with other influence operations, attribution continues to be a challenge for analysts focused on potential Chinese state activities, they add, citing a common misperception that all influence operations emanating from China are masterminded by the Chinese Communist Party. In some cases they have been attributed to pro-Beijing business figures who create pro-Beijing or anti-U.S. content “without orders or instructions,” or to nationalist internet users within China.

Transnational repression

China has successfully kidnapped and returned nearly 10,000 people who had fled overseas through its aggressive repatriation program, Operation Sky Net, which targets critics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), human rights defenders and other activists living abroad, UNPO reports. Through its Compromised Spaces campaign, UNPO has documented attacks and intimidation tactics by authoritarian states, which target diaspora communities in Europe and activists engaging with international fora. A recent report by NGO Safeguard Defenders has revealed the extent and severity of Operation Sky Net, China’s involuntary returns program, it adds.

China has successfully kidnapped and returned nearly 10,000 people who had fled overseas through its aggressive repatriation program, Operation Sky Net, which targets critics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), human rights defenders and other activists living abroad, UNPO reports. Through its Compromised Spaces campaign, UNPO has documented attacks and intimidation tactics by authoritarian states, which target diaspora communities in Europe and activists engaging with international fora. A recent report by NGO Safeguard Defenders has revealed the extent and severity of Operation Sky Net, China’s involuntary returns program, it adds.

Beijing is sports-washing its human rights record by using a relatively unknown Uyghur athlete to light the Olympic torch, says Minky Worden, the director of global initiatives at Human Rights Watch and the author of “China’s Great Leap: The Beijing Games and Olympian Human Rights Challenges.”

Civil society leaders, lawyers, women’s rights activists, journalists, and others have been arrested. And perhaps worst of all, China has been committing crimes against humanity in Xinjiang, mass incarceration, torture, sexual abuse, and forced labor, she tells PBS NewsHour. These are all crimes against humanity that are completely antithetical to the Olympic ideals.

How has the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) maintained its hold on China for more than seventy years? Why has China provided fertile soil for Chinese authoritarian ideology? Why doesn’t it have the resources to support the growth of democracy and freedom? Jinfeng Mu asks.

How has the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) maintained its hold on China for more than seventy years? Why has China provided fertile soil for Chinese authoritarian ideology? Why doesn’t it have the resources to support the growth of democracy and freedom? Jinfeng Mu asks.

The first reason, I think, lies in the limitations of the language surrounding democracy and human rights. In the older Chinese language, the word for democracy is the same as the word for monarch. Until modern times, there was no term corresponding to “Western democracy,” she writes for American Purpose:

Today, the word for “democracy” in Mandarin Chinese is “min zhu.” “Min” means people; “zhu” means master. The CCP has presented the meaning of “min zhu” not as “the people are the masters” but as “the people’s master.” In this way, a democracy that conforms to Beijing’s rules is substituted for real democracy.