U.S. citizens remain more internationalist than isolationist, but any new administration will need to revive and nurture frayed alliances with fellow democracies while attending to democratic revival at home, observers suggest.

Americans, like citizens of other countries, focus principally on problems at home. Elected leaders have always had to shape inchoate public attitudes into support for specific foreign policies, notes Robert Zoellick, a former World Bank president and author of ‘American in the World.’

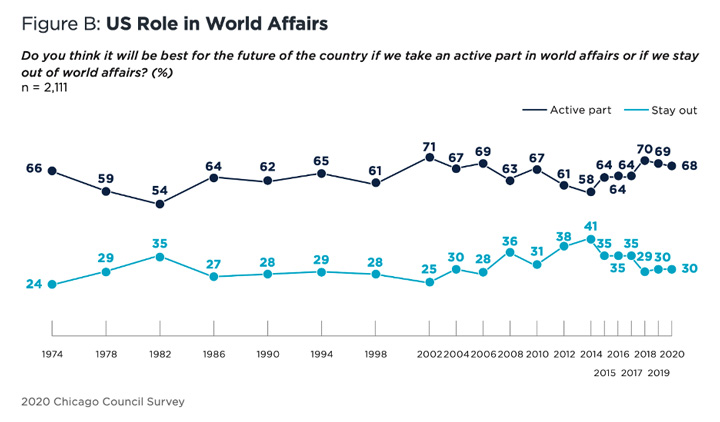

So the results of the 2020 annual survey of American public opinion on US foreign policy, from the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, may surprise doomsayers. A bipartisan 68 per cent favour the country taking an active part in world affairs — a share a little higher than during the cold war. Moreover, 68 per cent opt for a shared leadership role, compared with only 24 per cent preferring US dominance, he writes for The Financial Times:

So the results of the 2020 annual survey of American public opinion on US foreign policy, from the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, may surprise doomsayers. A bipartisan 68 per cent favour the country taking an active part in world affairs — a share a little higher than during the cold war. Moreover, 68 per cent opt for a shared leadership role, compared with only 24 per cent preferring US dominance, he writes for The Financial Times:

Americans are globalisers. Two-thirds believe globalisation benefits the US. Nearly three-quarters think international trade is good for the economy, 82 per cent agree that it benefits consumers, and 59 per cent believe it creates jobs at home. Support for NATO* has stayed steady at 73 per cent, and 71 per cent believe the US should consult with major allies before making decisions, even if Washington needs to agree to policies that are not its first choice.

“If a new administration rebuilds at home and revitalizes alliances abroad, the US will be better prepared to face the two biggest challenges: the future of free societies and China,” adds Zoellick, a former board member of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Fortunately, the United States can regain the initiative in the emerging competition with authoritarianism—if it addresses its vulnerabilities, leverages its strategic advantages, and reframes the contest on its own terms, according to Linking Values and Strategy: How Democracies Can Offset Autocratic Advances, a new analysis from the German Marshall Fund.

The United States faces an array of challenges—political polarization, inequality and racism, erosion of traditional media, a growing tech-government divide, flawed and porous political influence systems, and impaired economic competitiveness—that threaten to undermine the United States’ competitive strengths, says an Alliance for Securing Democracy task force of 30 leading American national security and foreign policy experts, including NED board member Scott Carpenter, National Democratic Institute president Derek Mitchell, and International Republican Institute president Daniel Twining.

Credit: Alliance for Securing Democracy

Autocrats can leverage these cleavages and constraints in the short-term, but in the long-term democratic characteristics confer tremendous strategic advantages, write analysts Jessica Brandt, Zack Cooper, Bradley Hanlon, and Laura Rosenberger. The United States’ advantages include a vibrant civil society, dynamic and competitive economy, innovative private sector, and robust network of alliances. Leveraging these strengths requires a national strategy to offset autocratic advances by seizing on the advantages of open systems, building resilience into democratic institutions, and exploiting the brittleness of authoritarian regimes. The logic and contours of such a national strategy across four overlapping non-military domains would include how to….

Leverage and Prioritize the United States’ Leading Advantages

- Seize the initiative in the information competition by executing a global campaign to expose the false promises of authoritarians while redoubling support for independent media and open access to information.

- Reinvest in alliances and international institutions by embracing multilateral democratic engagement to counter authoritarians.

- Leverage technology alliances to pool talent and resources, conduct joint research and development, collaborate on norm setting, and coordinate on investment screening.

- Prioritize engagement in standards-setting bodies to support the establishment of democracy-affirming global standards.

Share information and coordinate unified responses with allies and partners to counter and deter authoritarian interference efforts. RTWT

In recent weeks, Thomas Wright, director of the Brookings Institution’s Center on the United States and Europe and author of All Measures Short of War, has written at length about the choice facing an new administration, which he describes as pitting restoration against change. David M. Herszenhorn writes for POLITICO.

In recent weeks, Thomas Wright, director of the Brookings Institution’s Center on the United States and Europe and author of All Measures Short of War, has written at length about the choice facing an new administration, which he describes as pitting restoration against change. David M. Herszenhorn writes for POLITICO.

“It’s a choice between restorationists and transformationalists — and not to be too ageist about it, but a choice between the older crowd and the younger crowd, and it’s going to be really tough,” notes one observer. “But if you look at the Washington think tank people, more ideas for reviving the transatlantic relationship are coming from the younger generations.”

By appointing familiar faces like Karen Donfried, former senior director for European affairs on Obama’s National Security Council, two former ambassadors to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Dan Baer and Karen Kornbluh, as well as two former ambassadors to Russia, Sandy Vershbow and Michael McFaul, a new administration would send an important reassuring signal, said Susan Corke, director of the bipartisan Transatlantic Democracy Working Group.

“I wouldn’t expect anything particularly revolutionary,” Corke said. “Because the whole point is establishing normalcy, reestablishing our alliances, showing that we care about democracy and human rights again, sort of reassuring the world.”

“I wouldn’t expect anything particularly revolutionary,” Corke said. “Because the whole point is establishing normalcy, reestablishing our alliances, showing that we care about democracy and human rights again, sort of reassuring the world.”

Among America’s most important tools in defending democracy and countering authoritarianism are statements from its political leaders and high-level diplomats backing democratic moves in other countries and speaking out against autocratic ones, said Carnegie analyst Frances Brown, who served as the director for democracy on the National Security Council. Obviously, American denunciation was not enough to arrest authoritarianism, but it wasn’t meaningless, either, she told the NYT’s Michelle Goldberg.

“The idea of closer relations to the U.S. and Oval Office visits, a photo-op — that still matters to many leaders around the world,” said Brown. Besides, for better or worse, America would sometimes pair its rhetoric with economic pressure or limits on arms sales. “Those kinds of policies often do accompany public condemnation,” she said, though they tend to be “more under the radar.”

There is an important difference between the United States and other great powers in history, according to Atlantic Council analysts Peter Engelke and Julian Mueller-Kaler. As a liberal democracy, the country retains the capacity to rebuild and renew itself from within, they contend:

The ability to course-correct in the face of adversity is democracy’s greatest strength. Unlike in authoritarian states, lasting change in a democracy does not require a government collapse, a coup, or a bloody revolution. If the United States is to regain its lofty heights, Americans must take seriously a project of democratic restoration.

*The future of NATO was the subject of a discussion at the recent Estoril Political Forum 2020 on “New Authoritarian Challenges to Liberal Democracy” (above), featuring Jeff Gedmin

(American Purpose, Washington D.C.); John O’Sullivan (President, Danube Institute, Budapest); Lívia Franco (IEP-UCP, Lisbon); Michael Allen (NED/Democracy Digest, Washington D.C.)

Democracy at home is the source of American power abroad https://t.co/P9WCeoznq4 via @AtlanticCouncil

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 30, 2020