Connectas

Venezuela has more oil than Saudi Arabia and more poverty than Colombia. Once one of Latin America’s richest countries, it’s now plagued with shortages of everything from toilet paper to antibiotics and food, The Washington Post reports.

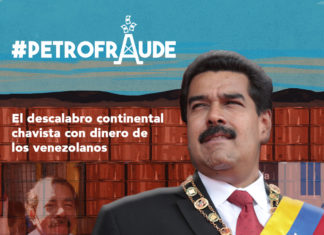

Venezuela negotiated energy agreements with 14 countries for the delivery of millions of barrels of oil in in a fraudulent system of overpricing and false deliveries in order to secure diplomatic allies at the expense of Venezuelan citizens’ welfare, a new investigation reveals.

The key to the international support that Nicolás Maduro’s regime maintains and that helps him avoid complete isolation has its own name: Petrocaribe, says a new report from Connectas. An energy and cooperation plan that injected more than 28 billion dollars into 14 countries, bought diplomatic endorsements, strengthened local elites, enhanced corruption and squandered the resources of people beset by shortages, it concludes.

Connectas

The geopolitical importance of the Petrofraude scheme is reflected in the regime’s use of the metaphor of “security rings”, typical of the military language, the report notes.

In several states, the scheme sought to facilitate the export of 21st Century Socialism, aiding leftist political parties and questionable social programs. Despite the huge investment of resources, no sustainable benefits were gained and the drop in oil prices exposed the fragility of the regime’s regional “assistentialism,” the authors add.

Payments, meant to be in kind, in many cases translated into an overpriced and fraudulent delivery system to benefit regional political alliances and local corruption instead of Venezuelans, the report adds.

Venezuela lost millions of dollars for accepting overvalued assets in exchange for oil, the #Petrofraude investigation reveals (Read:The business that emptied Venezuelan tables):

Venezuela lost millions of dollars for accepting overvalued assets in exchange for oil, the #Petrofraude investigation reveals (Read:The business that emptied Venezuelan tables):

- More expensive products. Nicaragua, Guyana, the Dominican Republic and El Salvador were the main players in the compensation system and Venezuela accepted overvalued assets from each of those countries, such as shipments of coffee from Nicaragua and rice from Guyana.

- Compensation without control. An internal audit of Petróleos de Venezuela (Pdvsa), the state oil company, revealed the absence of appropriate protocols by its PDV Caribe subsidiary PDV Caribe.

- Numbers that do not fit. #Petrofraude identified contradictions between the information on volumes and values of imported products from PDVSA and Venezuela’s Ministry of Food with declarations by the Venezuelan statistical authority, and official sources of the other countries involved. .

-

Connectas

Officials sanctioned or investigated. Key players in the oil and food exchanges between Venezuela and Nicaragua investigated or sanctioned by the US Treasury Department inclue Francisco López, a trusted confidante of Nicaraguan autocrat Daniel Ortega, and Venezuelan General Carlos Osorio, a “Tsar of food imports.”

- Privileged businessmen. Lucrative transactions favored companies linked to government leaders in the states benefitting from the oil agreements. Some operations under the compensation system were executed without the least public scrutiny.

The payments Petrocaribe made for non-existent infrastructure filled the pockets of at least three Presidents, several senators, and regional corporate groups. The plan to rebuild Haiti after the devastating 2010 earthquake is the best example of how corruption twice wounded citizens who placed hopes in these funds, Connectas notes.

For this #Petrofraude investigation, a journalistic team of five media reviewed detailed information on the program in the 14 beneficiary countries and conducted fieldwork in Nicaragua, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guyana and Venezuela. RTWT

#Petrofraude is a collaborative research led by the Latin American research journalism platform CONNECTAS in partnership with Confidencial de Nicaragua, El Pitazo de Venezuela, Diario Libre of the Dominican Republic and La Prensa Gráfica de El Salvador.