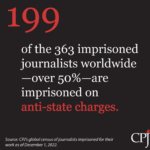

It’s been another record-breaking year for the number of journalists jailed for practicing their profession. The Committee to Protect Journalists’ annual prison census has found that 363 reporters were deprived of their freedom as of December 1, 2022 – a new global high that overtakes last year’s record by 20% and marks another grim milestone in a deteriorating media landscape, writes CPJ Editorial Director Arlene Getz.

It’s been another record-breaking year for the number of journalists jailed for practicing their profession. The Committee to Protect Journalists’ annual prison census has found that 363 reporters were deprived of their freedom as of December 1, 2022 – a new global high that overtakes last year’s record by 20% and marks another grim milestone in a deteriorating media landscape, writes CPJ Editorial Director Arlene Getz.

This year’s top five jailers of journalists are Iran, China, Myanmar, Turkey, and Belarus, respectively. A key driver behind authoritarian governments’ increasingly oppressive efforts to stifle the media: trying to keep the lid on broiling discontent in a world disrupted by COVID-19 and the economic fallout from Russia’s war on Ukraine. RTWT

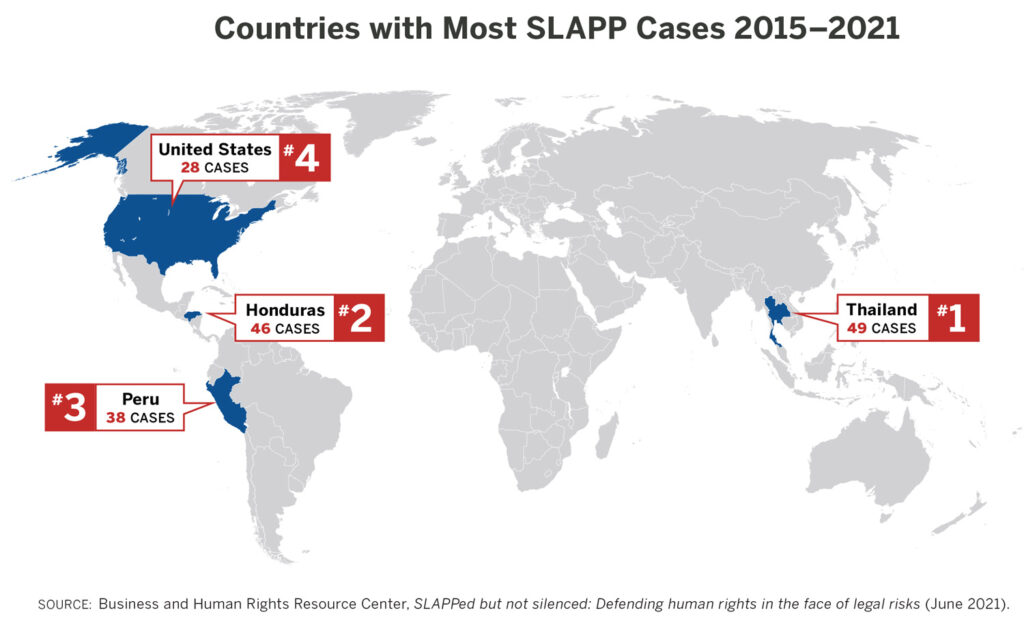

The weaponization of the legal system against independent journalism – especially in the form of strategic lawsuits against public participation, or SLAPPs – is an increasing threat to independent media globally, says a new analysis from the Center for International Media Assistance.

The weaponization of the legal system against independent journalism – especially in the form of strategic lawsuits against public participation, or SLAPPs – is an increasing threat to independent media globally, says a new analysis from the Center for International Media Assistance.

There are several novel approaches to address the growing threat of SLAPPs to independent media. In CIMA’s latest report, Fighting SLAPPs: What Can Media, Lawyers, and Funders Do?, Peter Noorlander discusses tactics that journalists, activists, and defense lawyers can use to defang SLAPPs, including setting up mutual insurance mechanisms, pooling resources, and advocating for changes to court rules. These measures can strengthen the resilience of media outlets and, as a carefully targeted package, can help alleviate the burden of defending SLAPPs. RTWT

If democracy is going to survive, we’re going to need to fund its watchdogs, says Julia Angwin, founder and editor-at-large of The Markup. A handful of journalism rescue efforts are already underway, she writes for NiemanLab. The International Fund for Public Interest Media is seeking to raise $1 billion to fund journalism around the world. The Biden administration has pledged up to $30 million to the fund — a decent start. In September, the European Union passed a law preventing member states from interfering with the coverage of publicly funded media.

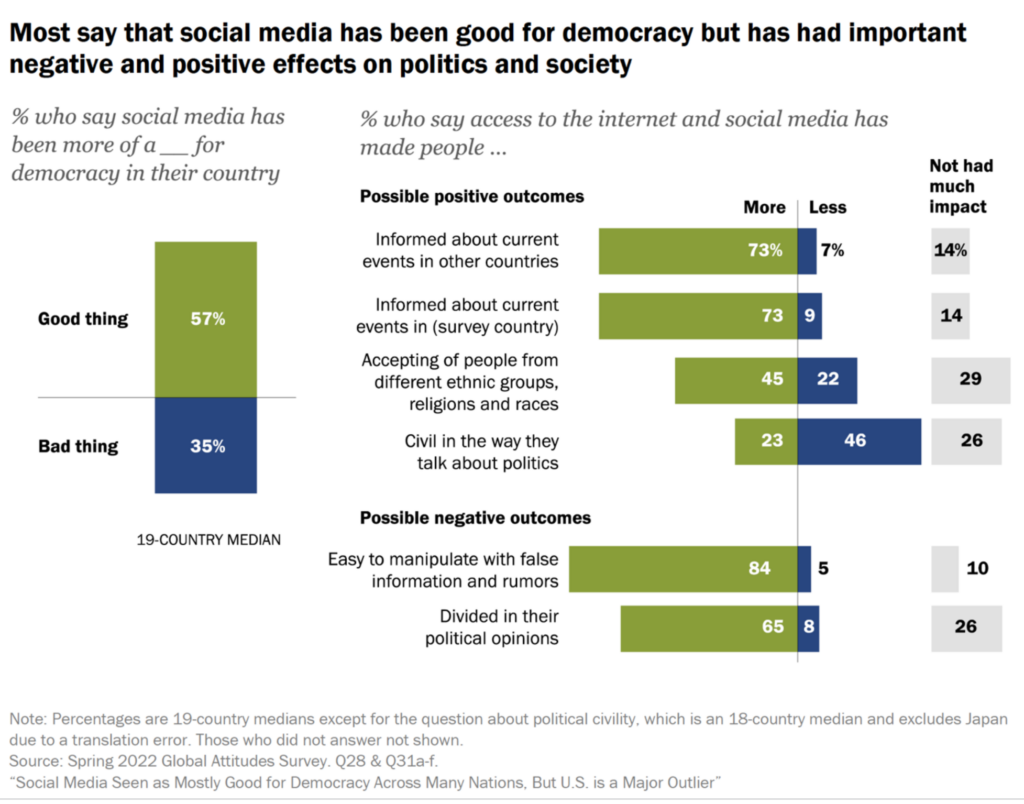

A new survey of 19 advanced economies shows that ordinary citizens see social media as both a constructive and destructive component of political life, and overall most believe it has actually had a positive impact on democracy. Across the countries polled, a median of 57% say social media has been more of a good thing for their democracy, with 35% saying it is has been a bad thing, the Pew Research Center reports.

There are substantial cross-national differences on this question, however, and the United States is a clear outlier: Just 34% of U.S. adults think social media has been good for democracy, while 64% say it has had a bad impact, it adds. In fact, the U.S. is an outlier on a number of measures, with larger shares of Americans seeing social media as divisive.

Disinformation matters. It can shape debate and it can change outcomes, notes British Security Minister Tom Tugendhat. This is because democracy isn’t just an event, it’s a process.

It’s how we talk to each other, not just how we decide the future in a ballot box, he told the Policy Exchange think tank this week. But how we shape that future through discussion. It’s as much about journalists, lawyers, businesses and civic activists as it is about politicians.

But democratic governments should be aware that the measures they adopt to address disinformation at home may be used to justify rights restrictions in less free environments, says a new Brookings analysis. In Asia, disinformation campaigns — perpetrated by foreign actors seeking to shore up power at home and weaken their competitors abroad and by domestic actors seeking political advantage — are increasingly putting pressure on democratic societies, notes analyst Jessica Brandt:

But democratic governments should be aware that the measures they adopt to address disinformation at home may be used to justify rights restrictions in less free environments, says a new Brookings analysis. In Asia, disinformation campaigns — perpetrated by foreign actors seeking to shore up power at home and weaken their competitors abroad and by domestic actors seeking political advantage — are increasingly putting pressure on democratic societies, notes analyst Jessica Brandt:

- Taiwan, which has been ranked as the country most targeted by false information since 2013, faces an onslaught of disinformation from China.[5] Puma Shen illustrates how the Chinese government uses disinformation in combination with other tools — including nontransparent funding and personal ties — to extend its influence.

- Maiko Ichihara details the spread of Russian propaganda in Japan about Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, and how these narratives are proliferated by Russian diplomats, domestic conspiracy theorists, and accounts that regularly amplify Chinese government content.

- Aim Sinpeng documents three key drivers of disinformation in Thailand: the campaigns of domestic political leaders that seek to attack opposition groups and shape public perceptions of government institutions; the growing influence of China in Thailand’s traditional media and technology landscapes; and the existence of a legal framework that gives state agencies power to exert control over information.

- In Malaysia, a combination of actors, often domestic, propagate disinformation in multiple local languages. Nuurrianti Jalli highlights how coordinated information campaigns surrounding elections in Malaysia have made it difficult for Malaysian citizens to make informed decisions about candidates and issues and have been used by leaders to gain and maintain power, contributing to democratic backsliding.

The knock-on effects of disinformation for democracy, social cohesion and public health (as evidenced by Covid vaccine scepticism) have been well documented. The integrity of democracy depends on voters being able to make informed choices and trusting the outcome of elections. Protecting a journalistic ecosystem that strives to report the truth is therefore not just a policy priority, but a national security one too, according to a new Nesta analysis:

The knock-on effects of disinformation for democracy, social cohesion and public health (as evidenced by Covid vaccine scepticism) have been well documented. The integrity of democracy depends on voters being able to make informed choices and trusting the outcome of elections. Protecting a journalistic ecosystem that strives to report the truth is therefore not just a policy priority, but a national security one too, according to a new Nesta analysis:

- Elisabeth Braw suggests that just as those on the domestic front in the Second World War were warned against irresponsible information-sharing, we need a modern “pre-bunking” service to protect citizens.

- Ethan Zuckerman looks ahead to a future where policymakers might get one step ahead of conspiracy theorists by using AI to simulate the more paranoid corners of the internet.

- David Halpern sets out an ambitious agenda for proper democratic governance of social media platforms—with rights, processes and user representation properly codified.

The intentional spread of falsehoods – and attendant attacks on minorities, press freedoms, and the rule of law – challenge the basic norms and values upon which institutional legitimacy and political stability depend, enhancing the anxieties of democracy, say the contributors to a recent book, The Disinformation Age.