Whatever Russia looks like after Putin, it may not be the Russia Western democracies want, one observer suggests.

Former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger used a nine-minute long video to call on Russia’s people to reject their government’s propaganda about the invasion of Ukraine.

The former body-building champion debunks the Kremlin’s talking points, including the spurious rationale of “denazification” of a state with a Jewish president and premier and the claim that Russian soldiers have sustained minimal casualties when the death toll is considerable higher than Russian officials concede.

Putin may soon be forced to concede that he cannot easily oust Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, according to a leading expert. The military situation has driven the Russians into a “grudging acceptance” of “Zelensky remaining president,” said Georgetown University professor Angela Stent – or at least that a pro-Russian puppet can’t replace him.

Unrest in Russia has not reached the level that would threaten Putin, she added. Twitter is rife with rumors of purges among the Russian security services. But none of it is likely to threaten Putin. Still, “things in Russia often appear stable until the next day they’re not,” said Stent, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of Putin’s World.

Unrest in Russia has not reached the level that would threaten Putin, she added. Twitter is rife with rumors of purges among the Russian security services. But none of it is likely to threaten Putin. Still, “things in Russia often appear stable until the next day they’re not,” said Stent, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of Putin’s World.

Instead of replacing Kyiv’s pro-Western government and permanently crippling its military, Moscow now appears prepared to accept a scenario in which Ukraine commits to being a neutral country with its own armed forces along the lines of Sweden or Austria, reports suggest.

Research of Russian immigration politics shows that populist and nationalist sentiment is growing, says former U.S. diplomat Esther Tetruashvily, a tech scholar and J.D. candidate at Georgetown University Law Center. The Russian middle class, disillusioned with the promises of Western capitalism, believe that their economic problems stem from immigrants taking their jobs and minority groups with outsized power, she writes for Foreign Policy:

In recent years, the greatest threat to Putin’s regime has come from domestic populist and nationalist opposition. Putin has had to strike a very careful balance, often promoting a nationalist identity that is not just Slavic but part of a Russian world that includes non-Slavic Russians. In recent years, Putin has used nationalist rhetoric to focus the animus of Russians hurting from Western sanctions toward Western leadership, especially the United States.

Whatever Russia looks like after Putin, it may not be the Russia Western democracies want, she states.

Whatever Russia looks like after Putin, it may not be the Russia Western democracies want, she states.

Putin “is still hoping to win.” But if there’s a stalemate, he said, any settlement will be “hard to accept” for both sides, a leading expert suggests.

“Putin would have to acknowledge that he waged a senseless war, killing thousands of Russian soldiers and thousands of innocent Ukrainians (ethnic Russians and Ukrainians alike), only to achieve what he de facto already had — control over Crimea and parts of the Donbas region as well as Ukrainian neutrality,” Stanford University’s Michael McFaul, a former U.S. ambassador to Russia, wrote for The Washington Post.

Zelensky “also would have to agree to conditions, including perhaps neutrality, that would be hard to accept” after everything his country has been through, he added.

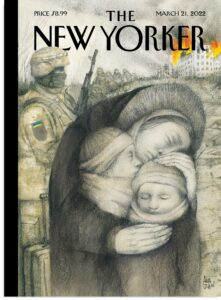

The war in Ukraine has shown that freedom and democracy can never be taken for granted, according to Ukraine’s civil society groups. Its networks, alliances and partnerships amplify the voices of those fighting to build and secure justice, uphold human rights, and preserve democracy,

The war in Ukraine has shown that freedom and democracy can never be taken for granted, according to Ukraine’s civil society groups. Its networks, alliances and partnerships amplify the voices of those fighting to build and secure justice, uphold human rights, and preserve democracy,

Nataliia Melnyk, coordinator for Ukrainian civil society, and Marta Barandyi, founder of the NGO Promote Ukraine, will participate in the inauguration of a Ukrainian civil society hub with the President of the European Parliament.

The Financial Times documents the country’s remarkable solidarity and resilience in ‘The birth of a new Ukraine’, explaining how Russia’s war united a nation.

The Financial Times documents the country’s remarkable solidarity and resilience in ‘The birth of a new Ukraine’, explaining how Russia’s war united a nation.

The war has led Ukrainians to unite in the face of a common threat: according to recent opinion surveys, which find that 91 percent of Ukrainians feel hopeful, while only 6 percent report feelings of despair.

Moscow, however, seems to want to raise the stakes, threatening to use chemical and nuclear weapons against Ukraine under the guise of a preventive strike. The fact that the Russian mass media seriously discuss the idea of Kyiv’s alleged developments of bacteriological and nuclear weapons confirms this could be an option, adds Mykola Vorobiov, a Ukrainian journalist and visiting scholar at Johns Hopkins University (SAIS).

With his actions in Ukraine, Putin opened a Pandora’s box—he destroyed the rules and foundations of the Yalta-Potsdam system of international relations and thus plunged the world into even more intense turbulence than that of the Cold War period, he writes for the Institute of Modern Russia.

European governments, including the UK’s, will have to be honest with their populations: defending democracy in Europe will be expensive, and consumers, industry and taxpayers will face additional burdens, say analysts Ian Bond, Elisabetta Cornago, Camino Mortera-Martinez and Luigi Scazzieri. Finally, European leaders need to be clear that however the conflict ends, anything like a return to business as usual with this Russia, whether under Putin or another authoritarian leader, would be a mistake, they write for the Centre for European Reform.

European governments, including the UK’s, will have to be honest with their populations: defending democracy in Europe will be expensive, and consumers, industry and taxpayers will face additional burdens, say analysts Ian Bond, Elisabetta Cornago, Camino Mortera-Martinez and Luigi Scazzieri. Finally, European leaders need to be clear that however the conflict ends, anything like a return to business as usual with this Russia, whether under Putin or another authoritarian leader, would be a mistake, they write for the Centre for European Reform.

In a mere 1,400 words an article by Journal of Democracy contributor Taras Kuzio explained the entire political and ideological background to Putin’s war, notes analyst David Stromberg. His Atlantic Council contribution titled “Inside Vladimir Putin’s criminal plan to purge and partition Ukraine,” Kuzio references a think piece in Ria Novosti, a state-owned news agency, published two days after the war was launched that announced “a new world being born under our eyes,” though it was later deleted, he writes for the American Scholar.