An estimated fifty thousand people in Moscow (Moscow Times/CFR) protested the barring of independent candidates from the ballot in an upcoming local election in what was one of the country’s largest demonstrations in years.

The military adventures of Mr. Putin, who celebrated 20 years in power last week, have turned Russia into a power to be reckoned with for foreign policy makers. But they haven’t translated into gains for average Russians, who have seen their living standards fall for five years in a row amid chronic economic problems aggravated by Western sanctions, The Wall Street Journal reports.

“The protests are about the deep disappointment Russians have in their government,” said Denis Volkov, a sociologist at Moscow-based pollster Levada. “It’s like the genie is out of the bottle and people can finally express their frustrations.”

The estimated 50,000 people who braved Moscow’s rainy weather were largely young adults who see themselves as ordinary people. A survey of every seventh participant, or a total of 306 people, at the security gates on Saturday aimed to “dispel persistent myths” surrounding the typical protester in this summer’s opposition rallies, The Moscow Times adds:

The estimated 50,000 people who braved Moscow’s rainy weather were largely young adults who see themselves as ordinary people. A survey of every seventh participant, or a total of 306 people, at the security gates on Saturday aimed to “dispel persistent myths” surrounding the typical protester in this summer’s opposition rallies, The Moscow Times adds:

Half of the respondents who attended Saturday’s protest said they were younger than 33, according to the survey. Eighty percent of respondents said that they permanently reside in Moscow, while another 17% said they live in the Moscow region….A majority, or 54%, of respondents said they perceived themselves as “ordinary people,” while 36% of respondents said “there are few people like me.”

“These figures show that these aren’t ‘intruders’ or school kids,” the authors, political scientist Alexei Zakharov and anthropologist Alexandra Arkhipova, wrote in Russia’s Vedomosti business daily Sunday.

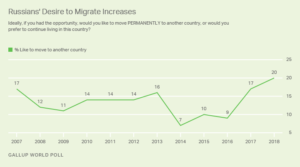

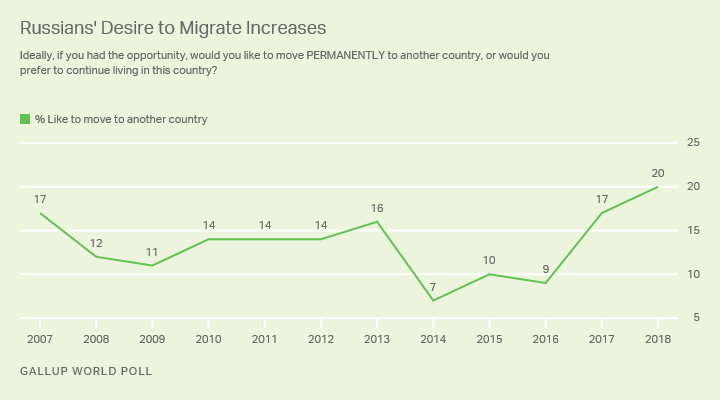

A recent Gallup poll made headlines in Russia with the revelation that a record 20 percent of the population wanted to leave their country.* Among younger Russians, the figure was far higher: For 15- to 29-year-olds, a staggering 44 percent indicated that they would like to migrate, The Washington Post adds:

A recent Gallup poll made headlines in Russia with the revelation that a record 20 percent of the population wanted to leave their country.* Among younger Russians, the figure was far higher: For 15- to 29-year-olds, a staggering 44 percent indicated that they would like to migrate, The Washington Post adds:

Young people have also voiced their discontent at home. They were at the forefront of recent protests in Moscow demanding that independent and opposition candidates be allowed to run in local elections this September. Protests in Yekaterinburg in May put a momentary end to the construction of a church in one of the inner-city parks. And large-scale protests in 2018 against pension reforms suggest broad dissatisfaction with the socio-economic conditions, and the regime’s difficulties in managing societal expectations.

Screenshot Youtube

Video footage of a police officer punching a young woman in the stomach (right) has stirred anger among many Russians who believe the authorities have used excessive force to disperse weeks of political demonstrations, The Moscow Times adds. The clip, filmed Saturday and later circulated online by Russian celebrities with millions of followers, shows the moment two helmeted riot policemen drag the woman, Daria Sosnovskaya, to a waiting police bus.

The current wave of protests have been described as “an important test” of Russia’s civil society.

What makes Moscow’s protests unique is the almost surreal peacefulness on the protesters’ part, notes Alexey Kovalev, head of investigations at Meduza, an independent Russian news aggregator. And unlike the gilets jaunes’ (yellow vests’) grand demands, the opposition’s goals seem almost insignificant in comparison: let opposition candidates stand in the Moscow City Duma – council – elections on 8 September, he writes for The Guardian. Yet opposition candidates were met with such forceful resistance that it became clear that the Kremlin won’t allow even the symbolic electoral presence of what its ideologues call “non-systemic opposition”.

What makes Moscow’s protests unique is the almost surreal peacefulness on the protesters’ part, notes Alexey Kovalev, head of investigations at Meduza, an independent Russian news aggregator. And unlike the gilets jaunes’ (yellow vests’) grand demands, the opposition’s goals seem almost insignificant in comparison: let opposition candidates stand in the Moscow City Duma – council – elections on 8 September, he writes for The Guardian. Yet opposition candidates were met with such forceful resistance that it became clear that the Kremlin won’t allow even the symbolic electoral presence of what its ideologues call “non-systemic opposition”.

OVD info

But the democratic coalition has a riot stick of its own – a clear advantage in the electoral struggle at this moment, notes Grigory Yudin, a professor at the Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences. Each of the candidates has thousands of supporters who are angry at the clear violation of their electoral rights, and will be ready to take their revenge via protest votes if their candidates aren’t allowed to run.

At the Moscow council elections, which have, as a rule, an extremely low turnout, this is a significant weapon – and one that could have a decisive influence on the outcome of the elections, he writes for Open Democracy.

Russia’s media regulator on Sunday asked Google to stop sending push notifications for livestream videos of anti-government protests and arrests, DW adds:

Roskomnadzor said it complained to Google about unspecified “structures” allegedly using tools, such as push notifications, to spread information about illegal mass protests, “including those aimed at disrupting elections.” The Russian watchdog said that if Google failed to respond to its request, it would consider it “interference in its sovereign affairs” and “hostile influence [over] and obstruction of democratic elections in Russia.”

Levada

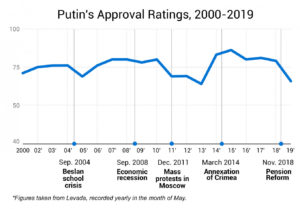

Russians now view the Brezhnev era in more positive ways than they do the Putin regime today, with roughly a quarter saying that it was closer to the people, strong, firm and justice and somewhat more saying that the current powers that be are corrupt, alien, bureaucratic, and short-sighted, according to a new Levada Center poll:

Putin’s relatively high ratings are regularly used to suggest that the Russian people are united in their positive assessment of the situation, the center’s sociologists say; but the new poll suggests that when Russians are offered almost any alternative, they see it as preferable to what they have now ….That explains why the Kremlin has worked so hard and up to now successfully to suggest that there is “no alternative” to Putin. (HT: Paul Goble).

Levada

According to the Levada Center poll, “only one or two percent of Russians say that they will take an active part” in political life and only 42 to 44 percent indicate they follow political events closely. But a majority – 54 to 57 percent – aren’t interested in politics at all.

OVD-Info keeps count of detained protesters who contact it through its hotline and automated bot on the popular Telegram messenger. The group then publishes regular updates on its website and social media accounts about those detained and those who sustained injuries during the arrests. It also helps them find legal support, The Moscow Times adds.

“In 2011 everyone was asking us why we needed to start a group like this, but already then it was clear to us what would happen and why we would be needed,” said Grigory Okhotin, one of OVD-Info’s co-founders. “There are strong ties between protesting and repressions. The more active civil society becomes, the more the repressions increase and the more people have a demand for us.”

OVD-Info

“They’re the heroes of our time,” said political scientist Yekaterina Schulmann. “Their work is developing a growing structure of citizens — both institutions and individuals — working together with enthusiasm to help protesters,” she told The Moscow Times:

Schulmann said the structure includes organizations like Glukhov’s Apologia of Protests and the Agora human rights group, both of which provide legal support for detained protesters. The movement also includes Telegram chats like “Delivery.Moscow,” started by three activists during the spring 2017 protests against corruption led by opposition politician Alexei Navalny. The chat now has nearly 3,000 volunteers that provide essentials — toothbrushes and toothpaste, wet wipes and toilet paper, bottles of water and crackers — to those detained for up to the maximum 48 hours.

Russia has more than once demonstrated the ease with which complex societies can fall apart. It has shown how difficult it is to uphold the legitimacy of nations and to install and sustain democratic regimes, argues Laura Engelstein, the Henry S. McNeil Professor Emerita of  Russian History at Yale University.

Russian History at Yale University.

We remember the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. A megapower suddenly vanished–the ideology that sustained it deflated like a punctured balloon, writes the author of Russia in Flames:

Alumni, like Putin, of the Soviet political police, the former KGB, used their insider status and institutional leverage to shape a new form of authoritarian rule. A pseudo-capitalist oligarchy arose on the ashes of Soviet Communism, while the welfare of the majority of the population eroded. What we now deplore as the increasing disparity between rich and poor in the developed industrial nations in Russia was an instant product of Communism’s collapse. Much has improved in the post-Soviet sphere; open borders, an uncensored press, freedom of speech and assembly (though increasingly imperiled), prosperity for the better off, not just the elite. But the rule of law is a mere fig leaf and the hope that free markets would result in a free society has not been fulfilled.

Putin faces a conundrum, argues Samuel A. Greene, Reader in Russian Politics and Director of the Russia Institute, King’s College London, and co-author of Putin v. the People: The Perilous Politics of a Divided Russia.

Putin faces a conundrum, argues Samuel A. Greene, Reader in Russian Politics and Director of the Russia Institute, King’s College London, and co-author of Putin v. the People: The Perilous Politics of a Divided Russia.

On the one hand, the immediate demands of political survival – from keeping fence-sitters out of the ranks of the opposition, to staving off challenges from a nervous elite – require him to demonstrate that he’s unafraid to use force against his own citizens, says Greene, author of Moscow in Movement: Power and Opposition in Putin’s Russia. On the other, because violence serves to galvanise the opposition, those very demonstrations increase the risk of a revolutionary spiral of escalation.

*