Democracy is not self-repairing. It requires constant attention, notes Fiona Hill, the Robert Bosch Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center on the United States and Europe. No country, no matter how advanced, is immune to flawed leadership, the erosion of political checks and balances, and the degradation of its institutions, she writes for Foreign Affairs.

Democracy is not self-repairing. It requires constant attention, notes Fiona Hill, the Robert Bosch Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center on the United States and Europe. No country, no matter how advanced, is immune to flawed leadership, the erosion of political checks and balances, and the degradation of its institutions, she writes for Foreign Affairs.

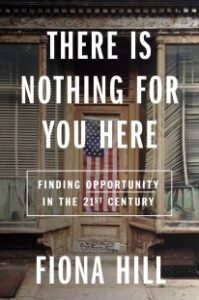

In the very early years of the post–Cold War era, many analysts and observers had hoped that Russia would slowly but surely converge in some ways with the United States. They predicted that once the Soviet Union and communism had fallen away, Russia would move toward a form of liberal democracy, adds Hill, the author of There Is Nothing for You Here: Finding Opportunity in the Twenty-first Century.

That didn’t happen.

Indeed, Russia’s political doctrine is profoundly at odds with the interests of Western democracies, says analyst Keir Giles. The current disagreement is not about Crimea, Ukraine or Syria; it is about a fundamental incompatibility of world views, and the dangerous implications of this clash for governments, societies and people, he writes for Chatham House, the London-based foreign policy think-tank.

The Kremlin has reduced the space of freedom to what it was at the end of the 1980s, according to former Soviet dissident Aleksandr Podrabinek. But many in Russia have a hard time seeing these changes because they have been gradual and Russians are inclined “to live by illusions” such as what appear to be elections and a market economy, a parliament and courts, “the illusions of democracy in an authoritarian state.”

According to the analyst, “the symptoms of totalitarianism are encountered in Russia ever more frequently,” analyst Paul Goble reports.

The Biden administration should rally Americans in support of democratic allies and base a new transatlantic agenda on the mutual fight against populism at home and authoritarianism abroad through economic rebuilding and democratic renewal, Brookings’ Hill suggests. RTWT

NDI

More broadly, the West’s democracies should follow the following principles for effective deterrence of Russia, Giles writes for Chatham House:

- Recognize the limits of agreement: It is a fundamental miscalculation to assume that Russia is interested in cooperation on Western terms, or that the West can improve the relationship through unilateral efforts. Conversely, a certain number of Russian attitudes are unshakeable. One is that the essential aim of Western policy is to expand its space of influence or bring about regime change in Russia. While Russia’s actions can be influenced through deterrence or dissuasion, basic assumptions of this kind cannot.

- Engage, but do not appease: Calls for ‘dialogue’ in Western discourse often suggest that policymakers should empathize with Russia, concede to its demands, or at the very least offer conciliation. There is, however, a clear difference between engaging with Russia productively and sacrificing interests and values to accommodate the Kremlin or cooperate on Russia’s terms. While dialogue is essential, what is said is even more crucial. Policy should not focus on appeasement, but should be about signalling determination and resilience to safeguard these values and interests.

- Avoid rewarding provocation: Russia has clear incentives to continue on its path of military provocation and non-military hostile activity. These incentives should be removed by establishing clear boundaries and parameters of acceptable behaviour, none of which impinges on the sovereignty or vital interests of the US or its allies. …

- Avoid self-deterrence: It is routinely suggested that clashes and close encounters may be the fault of the US or its allies for engaging in provocative behaviour. Russia does not necessarily consider deterrence to be provocative but the West needs to respond assertively in order to set boundaries and discourage, rather than encourage, further Russian brinkmanship. …

-

National Endowment for Democracy

Assess the full spectrum of threat: NATO allies differ among themselves over where, and how, Russia presents a threat, in part because of differing attitudes within Europe to Russia as a whole. This lack of coherence – for instance on whether Russian activity in the economic domain, such as the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, is in itself undesirable because it harms NATO partners – leaves gaps for exploitation by Russia and will increase its willingness to test resolve….

- Name and shame: Concealing the true nature, volume and intent of Russia’s irresponsible behaviour cedes the information space to Moscow instead of properly educating Western publics about the brinkmanship practised by Russia and the restraint required from NATO partners. In particular, it allows Russia to further the narrative that it is behaving responsibly and that NATO is the provocative actor. But most importantly, the lack of transparency over Russia’s hostile actions leads to an inadequate perception of threat among Western populations, and among those political leaders who receive the same information flows as them and are sensitive to public opinion. …. RTWT

Fiona Hill @ForeignAffairs: “Prior to the 2016 U.S. election, Putin recognized that the United States was on a path similar to the one that Russia took in the 1990s… The fire was already burning; all Putin had to do was pour on some gasoline.” https://t.co/KaoAN0k0Bg

— Brookings Foreign Policy (@BrookingsFP) September 27, 2021