Ukrainians’ willingness to engage in defending the country prior to the outbreak of war is predicted by strong feelings of Ukrainian nationalism. But it is also associated with the endorsement of democratic values among ordinary citizens, according to Pippa Norris and Kseniya Kizlova.

This is not just rhetoric; feelings of nationalism (our land), as well as the genuine desire to protect democratic freedoms (our rights), fuel activism in the resistance, they write for the LSE’s Europp blog. In Zelensky’s words to the European Parliament: “Our people are very much motivated, very much so, we are fighting for our rights, for our freedoms, for our life.”

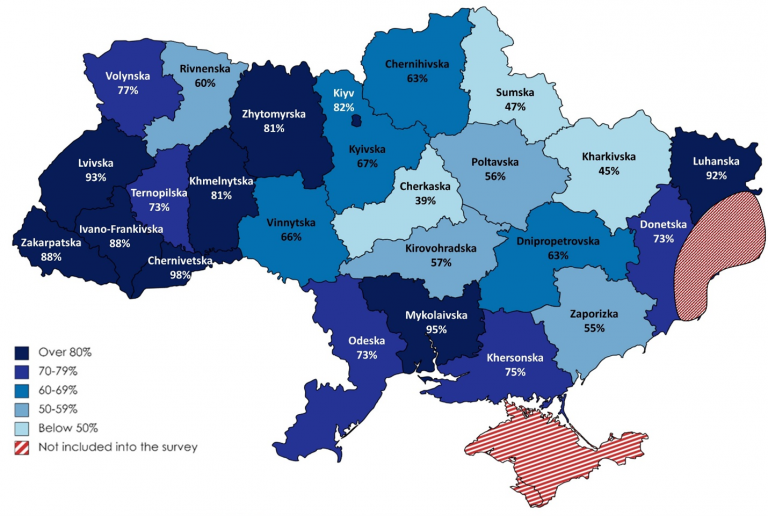

% of population prepared to fight against the invasion.

In a November 2021 International Republican Institute survey, for example, when asked about the three most important issues facing Ukraine, only 8% mentioned relations with Russia, Norris and Kizlova add. Clearly the intense shock of the current Russian invasion may well prove critical in changing attitudes and behavior, spurring many Ukrainians into action who might never have contemplated bearing arms before.

Protecting civilians, and especially human rights defenders both Ukrainian and foreign, is one of the most urgent non-military actions Ukraine’s allies can take, say Freedom House analysts Isabel Linzer and Yana Gorokhovskaia. They should coordinate to warn and, when desired by the individuals in question, extract and resettle vulnerable individuals.

Given the Kremlin’s track record of transnational repression across Europe, at-risk individuals should be given the option of swift relocation to geographically distant countries, like the United States, rather than remaining in border States where they are more vulnerable, they write for Just Security. Civil society organizations in a position to offer digital security training and socio-psychological assistance to members of civil society should be given ample funding to do this work.

“The sanctions imposed on Russia [make the country] an island, nearly completely isolated,” said Eric Honz, deputy regional director for Europe and Asia at the Center for International Private Enterprise, a core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

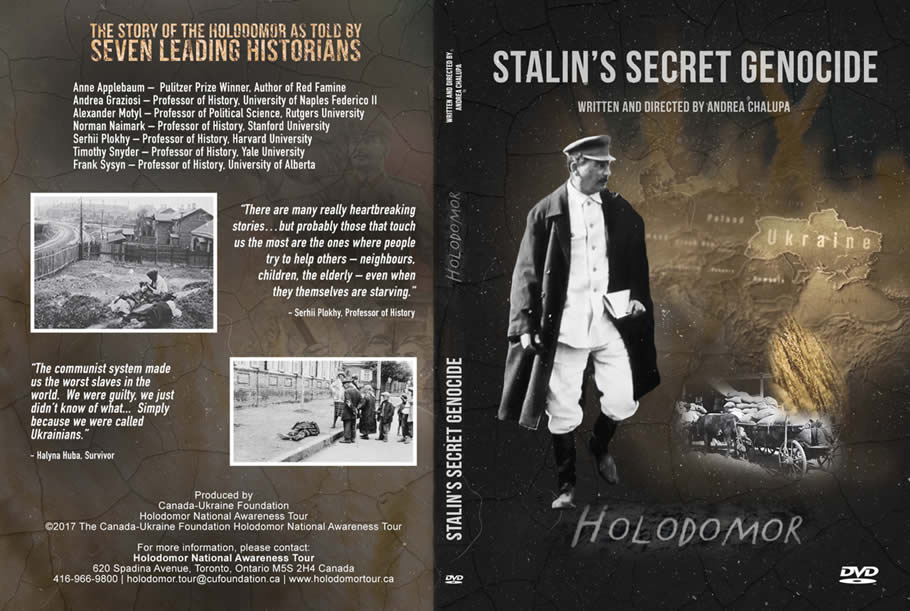

A Ukraine that is heading towards democratic freedom, the rule of law and integration with the West particularly galls Putin because Ukraine is ethnically Slavic and primarily Orthodox in religion, like Russia, says Stanford historian Norman Naimark. a co-author of Stalin’s Secret Genocide – Ukraine’s Holodomor. It shares the Russians’ own Soviet and Imperial past and therefore should be complicit, in Putin’s view, in Moscow’s anti-democratic ideology.

A Ukraine that is heading towards democratic freedom, the rule of law and integration with the West particularly galls Putin because Ukraine is ethnically Slavic and primarily Orthodox in religion, like Russia, says Stanford historian Norman Naimark. a co-author of Stalin’s Secret Genocide – Ukraine’s Holodomor. It shares the Russians’ own Soviet and Imperial past and therefore should be complicit, in Putin’s view, in Moscow’s anti-democratic ideology.

For Putin, it’s one thing if Estonia or Latvia has a well-functioning parliamentary democracy, Naimark tells Stanford News’ Melissa de Witte. These former Soviet republics that also share common borders with Russia did not have the same integral nexus with the Russia that Putin thinks Ukraine does. Ukrainian democracy is seen as threatening and undermines his sense of the larger Russian mission.

Putin has more or less admitted this to be the case, said Anne Applebaum, a Pulitzer prize-winning historian and a senior fellow at the SNF Agora Institute and SAIS.

“He had a line in one of his paranoid television appearances about ‘influence from the West coming to us from Ukraine,'” she said. “What he means is the influence of democratic ideas, ideas about transparency, about the rule of law—all of which could potentially damage his autocratic, kleptocratic political system that keeps him in power.”

Let all in the power vertical know they will be treated as war criminals. They are, Garry Kasparov tweeted. Every day Ukraine endures gives opportunity to communicate this catastrophe to the only people who can really stop Putin, the Russian people, from oligarchs to commanders to protestors.

Putin’s war on Ukraine has entered its next phase, one of destruction and slaughter of civilians. It is also a part of Putin’s World War, a war on the civilized world of international law, democracy, and any threat to his power, which he declared long ago. 1/13

— Garry Kasparov (@Kasparov63) March 2, 2022

In prescient comments from back in 2015, then NED President Carl Gershman stated: “Putin seeks nothing less than a different kind of world order from the one that followed the end of the Cold War and the breakup of the Soviet Union, which he has called “the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the twentieth century.” That’s why he “[drove] a tank over the world order,” as the Economist put it last March after the invasion and annexation of Crimea. Putin is seeking to reverse the verdict of 1989, as the American writer George Weigel has said, which he considers to be an unjust and humiliating defeat for Russia,” he wrote in A Fight for Democracy: Why Ukraine Matters, World Affairs, Vol. 177, No. 6 (March / April 2015), pp. 47-56.

Ukrainians are dying in defense of the democratic values they share with the United States, says Washington Institute Senior Fellow Dr. Anna Borshchevskaya, a former NED Penn Kemble fellow. In the above video, she describes the seven things everyone should know about the background of the Ukraine crisis, including the motivations of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Ukrainians are dying in defense of the democratic values they share with the United States, says Washington Institute Senior Fellow Dr. Anna Borshchevskaya, a former NED Penn Kemble fellow. In the above video, she describes the seven things everyone should know about the background of the Ukraine crisis, including the motivations of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Russia’s three-front invasion of Ukraine, and Kyiv’s unpreparedness despite weeks of Western warnings, highlight a key risk in strategic analysis – failing to appreciate how political ideology can at times bypass strategic logic, Stratfor’s Rodger Baker observes.

There was no pressing need for Russia to take a maximalist position on Ukraine at this time. But strategic logic can be subsumed by political ideology, clouding the overall strategic assessment and skewing the risk vs. reward ratio, he contends.

“We have a lot of attacks to kindergardens, schools and unfortunately civil buildings. The houses of ordinary people who even in the night could not sleep calm because they are afraid they won’t wake up in the morning.” Join the Alliance of Democracies tomorrow (see below).