Democracy is not in question, but the way we practice it is, according to a new analysis, which gathers available evidence for a European reality-check.

“One of the many drivers of populism is perceived government unresponsiveness rather than the desire to install authoritarian regimes,” according to Global Trends to 2030: Challenges and Choices for Europe from the European Strategy and Policy Analysis System (ESPAS).“It is this frustration that outsiders can tap into and feed in disinformation to destabilize our systems – but it is not a frustration that cannot be remedied.”

“How political leaders connect to citizens, how policy options are formulated, communicated and implemented will determine how well ‘democracy 4.0’ will be suited for the coming years,” the authors observe.

The next decade will be defining for the future of democracy and Europe’s role in the world, writes Ann Mettler, ESPAS Chair, due to:

The next decade will be defining for the future of democracy and Europe’s role in the world, writes Ann Mettler, ESPAS Chair, due to:

- seismic global power shifts… If, today, of the world’s eight largest economies, four are European (including the United Kingdom), by 2030, that number will be down to three (including the United Kingdom) and by 2050, only Germany is set to remain;

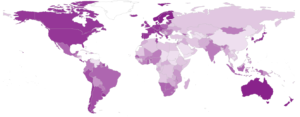

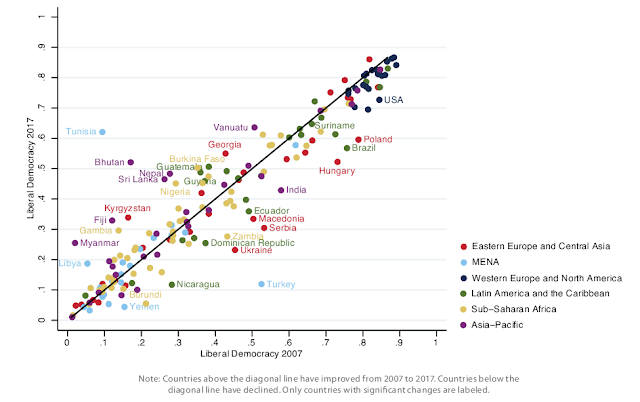

- pressure on liberal democracies… The world is becoming less free: If, until 2005, democracies and freedoms were expanding around the world, today they are in decline – a trend that has played out unabated in the last 13 years;

- challenges to global governance;

- the transformation of economic models and the fabric of societies;

- new uses and misuses of technology;

- contrasting demographic patterns; and

- humanity’s growing ecological footprint.

While it is clear that populism is triggered by crises, it is difficult to foresee the future of European populism. That said, we understand what populist parties thrive on, the report suggests:

While it is clear that populism is triggered by crises, it is difficult to foresee the future of European populism. That said, we understand what populist parties thrive on, the report suggests:

- Populism is not just about domestic concerns: when citizens feel that their state has lost global importance, they are more susceptible to populist messaging.

- Populism is not just a movement, it is also a political style, relying on emotional, and even overtly offensive language to stress the urgency of its demands, and their proximity to the people. Institutions like the EU do not easily master this style.

- Populism thrives on perceived social immobility; one of the ways to stimulate growth is to improve education, especially life-long learning for older generations.

“Measures to counter a populist narrative on inequality can include the strengthening of an inheritance tax to mitigate the accumulation of wealth, tax incentives for workers to invest in stocks, increasing measures against tax avoidance and evasion, and putting caps on top salaries,” the authors add. “But ultimately, populism is more than an economic phenomenon, [as the National Endowment for Democracy‘s Journal of Democracy has observed] and instead expresses a larger sense of malaise.”

“Measures to counter a populist narrative on inequality can include the strengthening of an inheritance tax to mitigate the accumulation of wealth, tax incentives for workers to invest in stocks, increasing measures against tax avoidance and evasion, and putting caps on top salaries,” the authors add. “But ultimately, populism is more than an economic phenomenon, [as the National Endowment for Democracy‘s Journal of Democracy has observed] and instead expresses a larger sense of malaise.”

Protecting democracy

Populism is not defeated by adopting its style, but by addressing the underlying fears of insecurity – and challenging negative narratives with positive ones. Protecting democracy therefore includes:

- closing the gap between citizens and governments by making it more visible and approachable (at local and regional levels, for instance);

- developing a relatable (rather than technocratic) narrative, and

- reinvigorating the European vision as something more than just economics – but a desirable way of life well-suited to manage the future.

- ‘populist-proofing’ democratic critical infrastructure,especially oversight and accountability mechanisms, will be key to protect democracies in the case of a populist government interlude.

- Once in government, populists are often tempted to hollow out the rule of law and certain basic freedoms (e.g. press), gradually eroding democracy. Strengthening the rule of law will therefore protect us from such populist erosion.

New data shows that the global trend of democratic declines continues in 2018. By end of 2018, liberal democratic institutions are eroding noticeably in 24 countries, home to one third of the world’s population, writes V-Dem’s Anna-Karin Lundell.

New data shows that the global trend of democratic declines continues in 2018. By end of 2018, liberal democratic institutions are eroding noticeably in 24 countries, home to one third of the world’s population, writes V-Dem’s Anna-Karin Lundell.

“Democracy is in decline in an unprecedent high number of countries around the globe,” she adds. “At the same time, the resilience of most democracies in the light of global challenges – digitalization, immigration, financial crisis – gives reason to be optimistic about the future of democracy.”

Democracy needs a “comprehensive national restoration and renewal” argues Os Guinness, author of “Last Call for Liberty: How America’s Genius Has Become Its Greatest Threat.” That requires “an expanded understanding of ‘liberty and justice for all’ to match modern conditions,” he writes for The Washington Times.

Testing the Resilience of Brazil’s Democracy

Testing the Resilience of Brazil’s Democracy

The last five years have exposed the fragilities of Brazil’s democracy, amidst widespread corruption investigations, growing polarization, and deep economic uncertainty, the Woodrow Wilson Center adds (see above):

The election of far-right populist Jair Bolsonaro to the presidency in October 2018 further exacerbated divisions, underscoring difficult questions about the quality and long-term sustainability of the country’s political system, built on the Constitution of 1988. Professor Oscar Vilhena Vieira, a gifted jurist and political scientist, offers sobering answers to these questions, as well as several recommendations to strengthen governance and democratic institutions in his new book A Batalha dos Poderes—a comprehensive analysis of the battles fought over the past thirty years by (and between) all three branches of government that have shaped Brazilian democracy.

Wilson Center

Democracy can recover from recent setbacks both in Europe and internationally, the ESPAS report insists, but only “if we take action”  in line with this scenario:

in line with this scenario:

- The stabilisation of Tunisia’s system, thanks to European support, proves to citizens in the broader region that democracy is beginning to make inroads in the Middle East and North Africa.

- In Europe, reduced rates of inequality, relatable political styles and positive economic developments mean that populist parties lose support.

- Regulated migration, assisted by integration programmes, reduces xenophobia and increases equality.