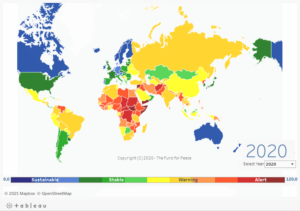

The return of strategic competition between states is an established geopolitical trend. But states themselves are getting more fragile, according to the 2021 Fund for Peace Fragile States Index, which shows an increase in nations hovering on the brink of state failure, including Mali, Nigeria, Venezuela and Syria, notes analyst Anastasia Kapetas.

The Global Fragility Act, passed at the end of 2019, prioritizes US engagement to stabilize fragile states and calls for the US government to do this in a coordinated way across the departments of Defense and State and USAID, she writes for ASPI’s Strategist. That’s something the US doesn’t do well, according to Frances Z. Brown, former director for democracy and fragile states on the National Security Council staff and senior fellow and co-director of Carnegie’s democracy, conflict and governance program.

“We’ve been talking for years in the international policy community about the need to work politically in fragile states. But we still really have yet to figure out how we operationalize that insight.” The costs of political failure have been high. According to Brown, “The Taliban victory was much more a psychological and political victory than a military conquest. They were able to take territory without firing a shot.”

In some cases, fragile states are more susceptible to meddling from Beijing or Moscow and, therefore, central to our competition with these adversaries, according to Patrick W. Quirk, Senior Director for Strategy, Research, and the Center for Global Impact at the International Republican Institute.

In some cases, fragile states are more susceptible to meddling from Beijing or Moscow and, therefore, central to our competition with these adversaries, according to Patrick W. Quirk, Senior Director for Strategy, Research, and the Center for Global Impact at the International Republican Institute.

In addition to carefully assessing the likelihood that such risks will impinge on U.S. interests, and devising means to address them, the White House should give particular attention to two issues, he writes for the National Interest:

- The first is dealing with the proliferation of non-state armed groups across every major region. Non-state armed actors like terrorists, rebel groups, and militias contribute to instability by offering governance alternatives that imperil a government’s legitimacy, contest the host government’s monopoly on the legitimate use of force, and enable illicit economies…..The NSS should include guidance on reassessing how and when the U.S. government engages such groups including, when interests align, as stabilization partners.

- The second threat from fragile states is the danger it poses to the Biden administration’s commitment to tackle corruption globally…. Weak institutions captured by predatory elites underwrite corruption in such countries. Therefore, using diplomacy and foreign assistance to strengthen democracy and good governance in fragile settings would serve the dual purpose of mitigating instability risks from fragile settings and curbing corruption. But the United States must go further by targeting the enablers and facilitators of corruption in regional states and the West.

The West faces stiff competition for influence in development policy in general, and in fragile states specifically, say Brookings analysts Bruce Jones and Alexandre Marc. If the West is divided, China will gain ever-more influence in these countries and in the multilateral institutions through which responses to their challenges are often organized and have a freer hand to pursue approaches corrosive to inclusive or democratic governance, peacebuilding and financial sustainability of fragile states, and Western interests, they write in a new report, The new geopolitics of fragility: Russia, China, and the mounting challenge for peacebuilding.

The West faces stiff competition for influence in development policy in general, and in fragile states specifically, say Brookings analysts Bruce Jones and Alexandre Marc. If the West is divided, China will gain ever-more influence in these countries and in the multilateral institutions through which responses to their challenges are often organized and have a freer hand to pursue approaches corrosive to inclusive or democratic governance, peacebuilding and financial sustainability of fragile states, and Western interests, they write in a new report, The new geopolitics of fragility: Russia, China, and the mounting challenge for peacebuilding.

“Are We Rome?” Cullen Murphy’s book with that title was published in the US in 2007, capturing the concern that America was an empire in decline. Today, the fashionable question in Washington is “Are we Weimar?” Is America, like Germany in the 1920s, a democracy in terminal decline? FT analyst Gideon Rachman observes. These twin fears — Rome and Weimar — are linked. Internal and external weaknesses feed off each other. Conventional accounts of the fall of Rome, stress both the barbarians on the frontiers of the empire and the rot at its center.

The future of American leadership in the world is uncertain, notes former NED president Carl Gershman, and as Sam Huntington used to say, a world without U.S. leadership and primacy would be a more violent and disorderly world, with less democracy and economic growth than, a world in which the U.S. exercised more influence than any other country.

The future of American leadership in the world is uncertain, notes former NED president Carl Gershman, and as Sam Huntington used to say, a world without U.S. leadership and primacy would be a more violent and disorderly world, with less democracy and economic growth than, a world in which the U.S. exercised more influence than any other country.

We have to redouble our efforts to strengthen and broaden democratic cooperation and unity. This means that other countries – small countries and mid-level powers – are going to have to play a larger role to make up for the deficit and fill the vacuum, he said in remarks upon receiving the Prague-based Forum 2000’s International Award for Courage and Responsibility.

“For more than three decades, Mr. Gershman’s unwavering dedication to promoting democracy and facilitating democratic unity worldwide has set an example for us all,” said Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen.

Leadership in the struggle to advance and defend democracy is going to have to come more from civil society, from the grassroots, Gershman added, meaning that civil society, to revise an Obama phrase, is going to have to lead from the front, and that democracy will increasingly depend on Havel’s “power of the powerless.”

Leadership in the struggle to advance and defend democracy is going to have to come more from civil society, from the grassroots, Gershman added, meaning that civil society, to revise an Obama phrase, is going to have to lead from the front, and that democracy will increasingly depend on Havel’s “power of the powerless.”

The Biden administration’s foreign policy—strengthening democracy at home and abroad—and the forthcoming Democracy Summit, which could formally enshrine democracy strategy in the national security agenda, might also align with the fragile states agenda, ASPI’s Kapetas observes. But, bureaucratically, fragile states are addressed in different silos to those focused on pushing back rising illiberalism.

“We have people working on democracy in one camp, and people that work on conflict and deploying to warzones in another. We have this assumption that a country is in the conflict basket and then it suddenly transitions to being in the democracy basket, and that’s not really how the world works,” says Carnegie’s Brown.

In addressing fragility as part of the NSS, the White House should consider two steps to address these challenges, among others, argues Quirk, a Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, and an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University:

- First, the Biden team should ensure its executive branch agencies effectively implement the “U.S. Strategy to Prevent Conflict and Promote Stability,” as called for in the 2019 Global Fragility Act (GFA). The next step in implementing the GFA is for the White House to select the five countries where it will pilot the strategy. ..

- Second, the White House should refresh or establish new multi- and bilateral partnerships to make addressing threats from fragile states as cost-effective as possible…..RTWT

The World Movement for Democracy hosts a Facebook Live discussion, “Crossover: A Strategy for Making Democracy Deliver,” in collaboration with the Sarajevo-based Advanced Leadership in Politics (ALPI). Please join on October 21, 2021 at 8:00 AM EDT to hear from the experiences of Jose Ramos-Horta (Timor Leste), Magdalena Vucina (Bosnia and Herzegovina), and Timur Vilic (Bosnia and Herzegovina), moderated by NED’s President & CEO Damon Wilson. More information on the event are available on the Eventbrite page. Register by October 20, 2021.

A recent IMF event aimed to take stock of the economic and social impact of COVID-19 in fragile and conflict-affected states (FCS), and identify pathways for progress toward resilient recovery (below).