Isolated and dysfunctional, Iran’s Islamic Republic had reached a dead end. “The regime has lost all popular support, and yet it is incapable of change,” a leading dissident tells the New Yorker’s Dexter Filkins.

Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran’s theocratic system, did not always project menace, he writes:

Fariba Adelkhah

When he was first chosen to be the Supreme Leader, he was seen as weak, lacking the respect of his fellow-clergymen. So he turned to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. To build support, he reached far down into the ranks and appointed new colonels and brigadiers….The I.R.G.C. became the principal basis of Khamenei’s power. In turn, he made it the country’s preëminent security institution.

“Khamenei micromanages the whole system, so everyone is loyal to him,” Khalaji, of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, said. “He is hyperactive. He knows every low-ranking commander and even the names of their children.”

Nearly one year after she was detained in Tehran, Iranian-born French anthropologist Fariba Adelkhah (above) was sentenced to a total of six years in prison under “national security” charges that Iranian prosecutors have used to jail several Iranian dual nationals in recent years, the Center for Human Rights in Iran reports.

“This revolting and completely unacceptable news arouses the anger, the sadness and the indignation of all of us, but it will not lead us to give up hope,” said a statement by Olivier Duhamel, president of the Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques and Frédéric Mion, President of Sciences Po. “This latest injustice only mobilizes us more than ever to work still more tirelessly in securing Fariba’s liberation,” it added.

“This revolting and completely unacceptable news arouses the anger, the sadness and the indignation of all of us, but it will not lead us to give up hope,” said a statement by Olivier Duhamel, president of the Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques and Frédéric Mion, President of Sciences Po. “This latest injustice only mobilizes us more than ever to work still more tirelessly in securing Fariba’s liberation,” it added.

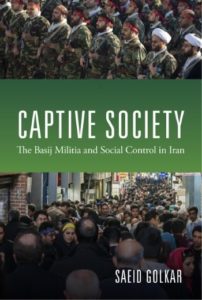

During the Green Movement, the Guard and its plainclothes militia, known as the Basij, were instrumental in crushing dissent. According to Abbas Milani, the director of the Iranian Studies program at Stanford and a former political prisoner in Iran, the uprising amounted to a political anointment, Filkins adds.

“Clearly, the regime believed it was going to lose control, and the I.R.G.C. and the Basij saved the day… The result is that the I.R.G.C. now has the upper hand. Khamenei knows that without the I.R.G.C. he’d be out of a job in twenty-four hours,” he observes:

The most visible symbol of the I.R.G.C.’s strength is the Basij, whose members can be seen on street corners in every Iranian city. A less visible measure is its manipulation of the economy. When the clerics took hold, after the revolution, they secured control of large sectors of the economy, including oil production, factories, and ports. During the next two decades, an array of state-owned enterprises were privatized—but, rather than going to skilled businesspeople, many of them were acquired by the I.R.G.C. and its associates.

Today, elements of the Guard are thought to own construction companies, oil refineries, and mines, along with a nineteen-story luxury mall in a posh neighborhood of Tehran. No one is entirely sure how much of the economy the group controls; credible estimates range from ten per cent to more than fifty. One indication of its wealth came in 2009, when its investment arm paid $7.8 billion for a majority stake in the Telecommunication Company of Iran; the I.R.G.C.’s total budget, on paper, was only five billion. In Iranian society, the Guard has grown into an untouchable élite. RTWT

Today, elements of the Guard are thought to own construction companies, oil refineries, and mines, along with a nineteen-story luxury mall in a posh neighborhood of Tehran. No one is entirely sure how much of the economy the group controls; credible estimates range from ten per cent to more than fifty. One indication of its wealth came in 2009, when its investment arm paid $7.8 billion for a majority stake in the Telecommunication Company of Iran; the I.R.G.C.’s total budget, on paper, was only five billion. In Iranian society, the Guard has grown into an untouchable élite. RTWT

Alireza Alinejad was arrested in Iran for the crime of being the brother of Masih Alinejad, (right), an exiled journalist and prominent critic of the clerical regime’s human rights abuses. If he were to denounce her, he might be released, but he will not, Roya Hakakian writes for the Independent.