Credit: POMED

Tunisian President Kais Saied has put in place special measures for wielding legislative and executive power, the presidency said on Wednesday, without elaborating, Reuters reports. It added that Saied would form a committee to prepare amendments to Tunisia’s political system and that he would maintain the suspension of parliament that he declared in July.

Saied denies having dictatorial aspirations and defends his actions as constitutional, but two months after sacking the prime minister, suspending parliament and assuming executive power he has made no clear statement about Tunisia’s future, Reuters adds.

His critics, drawn from across Tunisia’s political spectrum and among the most engaged elements of civil society, say he is inexperienced, isolated and uncompromising, and fear that when economic frustrations breed opposition, he will grow autocratic.

Western pundits have been quick to claim recent events in Tunisia are evidence of a ‘failed democracy experiment’. But analysts Hager Ali and Ameni Mehrez insist that the protests are more a testament to democratic resilience than failure. Recent unrest – in the first half of 2021 there were almost 6,800 protests, many largely unreported outside the country – are an indicator that institutional adjustments are overdue, they contend.

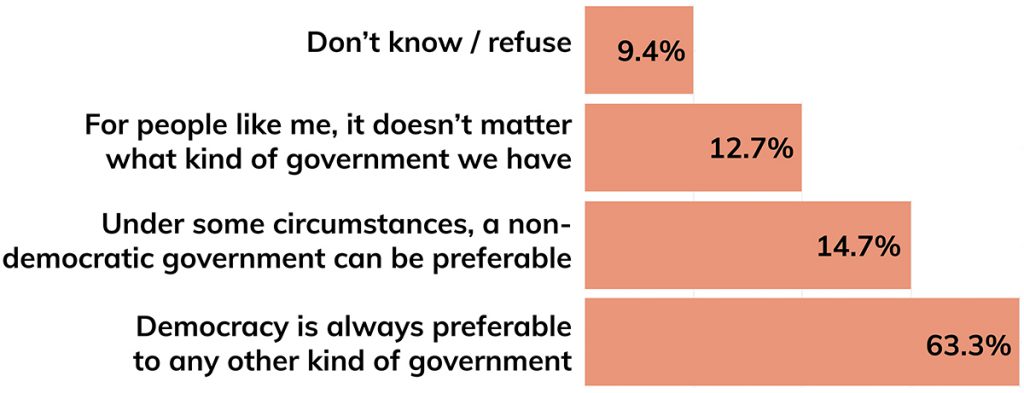

Citizens took to the streets recently to highlight the current administration’s failure to meet citizens’ recent and pre-Arab Spring demands. But this dissatisfaction does not extend to democracy itself, as Arab Barometer data shows:

Credit: Arab Barometer

Tunisia’s authoritarian turn is all the more disturbing since it was the “lone democratic experiment” to emerge from the Arab Spring, Carnegie analyst Michele Dunne told a National Endowment for Democracy forum.

Yet it also raises an intriguing question.

How do we think about the problem of leaders who aren’t elected, but who have the overwhelming endorsement of the bulk of their populations? CSIS analyst Jon Alterman asks Tunisia expert Monica Marks.

POMED

Not many people at all in Tunisia have been sad to see the political parties that were in parliament shut out, but this notion that the entirety of the Tunisian electorate has somehow turned their back on democracy is wrong, she observes. I actually think one of the most tragic things about the current situation in Tunisia is that so many people hope that Kais Saied can bring them a more representative form of government, and it’s a hope, born of desperation, adds Marks.

Those who know Saied see evidence of both populist hero and dangerous demagogue: an uncompromising ideologue unwilling to listen to others, yet one who lives modestly, shows compassion for the poor and insists that his goal is simply to wrench power from corrupt elites, The Times reports.

“His supporters see in him the last, best hope to achieve the goals of the revolution that were never realized,” said Marks, a Middle East politics professor at New York University Abu Dhabi. “But we know clean people who genuinely want to achieve good aims can sometimes turn into people who chop off heads.”

An Afrobarometer poll found that the Tunisian army was seen as the most reliable institution in the country, Deutsche Welle adds. Tunisians — 85% of them — trusted their soldiers more than their police, religious leaders, the judiciary or local and federal politicians.

“Perhaps sensing this public feeling, the Saied government is starting to wrap itself around the Tunisian armed forces,” said Olfa Hamdi, co-founder of the Washington-based Center for Strategic Studies on Tunisia.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to Saïed’s power grab on July 25 for two reasons, argues Sharan Grewal, an assistant professor of government at the College of William & Mary, a nonresident senior fellow at POMED, and a nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution:

- it exacerbated the economic and political crisis that then facilitated Kaïs Saïed’s actions

- Saïed’s relatively more effective response to COVID-19 in the past couple of weeks has helped legitimate his takeover of the government.

International Republican Institute

While polling data suggesting between 87 – 94 percent of respondents supported Saïed’s actions should be taken with a grain of salt, it is likely that a majority of Tunisians are supportive of Saïed and in particular his more effective response to COVID-19. In that sense, COVID-19 has both contributed to and now helped legitimate Kaïs Saïed’s power grab, he writes for POMED, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

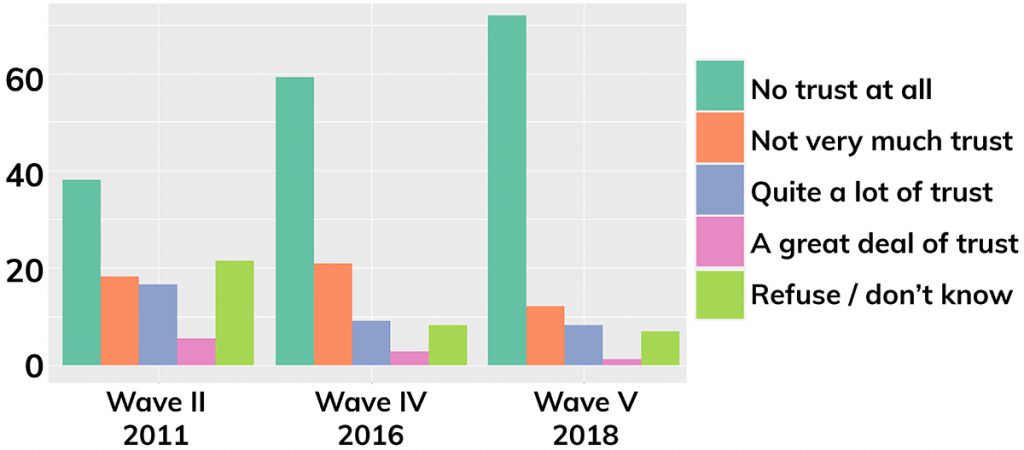

Arab Barometer Data from Tunisia shows distrust in political parties is not only high, it has increased drastically since 2011, analysts Ali and Mehrez write for ECPR’s The Loop.

Credit: Arab Barometer

Key democratic norms in Tunisia norms that were young and just in the process of concretizing have been demolished, for the time being, by Kais Saied, Marks tells Alterman.

After previous threats to democracy like the 2013 Bardo crisis that was ultimately resolved with the help of a Nobel Peace Prize winning quartet of Tunisian civil society organizations, Tunisians clawed themselves back through negotiation and dialogue, add Marks, but this time….

As time goes by with every passing week and month passing without any kind of roadmap back to a democratic path or representative form of government, it becomes harder for international partners—be they Western democracies or aid organizations tied to the interests of Western democracies—to make the case that Tunisia is the first and only democracy in the Arab world.

Tunisia’s democracy is under challenge, but not under threat https://t.co/EXEhgGrMiS

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) September 22, 2021