U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said on Tuesday that Tunisia’s “dream of self-government” was in danger, adding to U.S. criticism of the president’s expansion of powers that has already prompted accusations of “unacceptable interference,” Reuters reports.

As Tunisia’s President Kais Saied solidifies his control under a newly passed constitution, he will be challenged to deliver on promises of jobs, bread and stability for citizens, adds VOA’s Lisa Bryant (above):

Tunisia’s future—and Saied’s—may depend on a raft of factors, observers say: from whether the president can both secure and sell a crucial International Monetary Fund loan and its tough austerity requirements to save the country’s moribund economy, to the calculations of powerful players such as the country’s main trade union and revered army. Also shaping the country’s trajectory will be whether Saied can retain his fading but still-sizable support — and whether Tunisians have the will and energy to return to the streets if they believe yet another government has failed them.

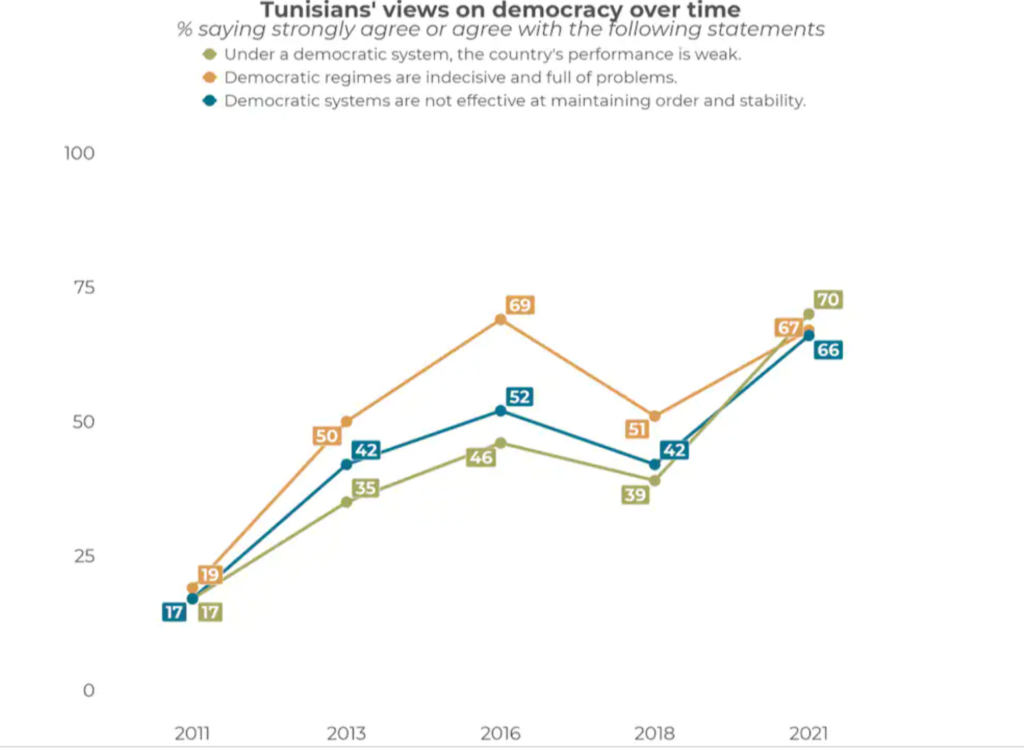

Arab Barometer

The widely boycotted referendum which consolidated Saied’s power has prompted experts to ask whether it spells the end of Tunisia’s democratic experiment.

“We are in real uncertainty,” said Tunis University political science professor, Hamadi Redissi. “If Saied improves people’s economic and social conditions, he will probably be reelected. But if his only obsession is the constitution and elections, the country will probably plunge into crisis.”

Tunisia analysts are writing the eulogy for the country’s democracy. Yet they’re missing out on another story, according to Meshkal journalist Ghaya Ben Mbarek and Aymen Bessalah, a nonresident fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy: Young Tunisians ― who participated in the 2011 uprising that ousted dictator Zine el Abidine ben Ali after 23 years of rule, and have consistently taken part in protests in the decade that followed ― feel otherwise. Tunisia’s youth are preparing for the battles to come. They’re focused on a renewed sense of resistance against all political elites, they insist.

Three scenarios await Tunisia under Saied, only one of which will actually be fathomable or workable in the foreseeable future, Georgetown University’s Daniel Brumberg writes for the Washington DC-based Arab Center:

Three scenarios await Tunisia under Saied, only one of which will actually be fathomable or workable in the foreseeable future, Georgetown University’s Daniel Brumberg writes for the Washington DC-based Arab Center:

Qadhafi Lite: The least likely option for Tunisia going forward is a version of late Libyan dictator Muammar Qadhafi’s system of rule. ….At first blush, Kais Saied seems to possess the personality and skill set to build this system. He has advocated a utopian, locally-based “popular” democracy. He also projects a kind of charisma that is telegraphed by his rejection of all formal political institutions and his mystical faith in his own judgment. …. But Tunisia is not Libya; it is not a tribal society with an economy based on distributing oil income to regionally-based strongmen.

A Presidential-Military Regime: This would be a version of Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi’s regime, but perhaps with less outright repression. The concentration of power in the executive that Saied’s constitution sets out would support this system. But fully aligning the military with this project would require an even closer relationship than Saied has managed to establish so far…. A presidential-military regime would certainly provoke resistance from almost all of the country’s political parties and civil society groups, as well as the legal community and independent media. But the capacity of these groups to effectively oppose Saied would ultimately depend on the UGTT [labor confederation]. …

A Liberalized Autocracy: While allowing for a measure of openness and competition, a liberalized autocracy ensures a hobbled pluralism, one that is ultimately limited by a very powerful president. In such a scenario, Saied would be the final arbiter of a political arena that would have just enough contending parties and groups to facilitate a strategy of divide and rule. Some electoral and ideological competition and inclusion would be necessary to play Islamists and secularists off of each other, or to set the rural population against the urban elite, or to encourage competition between the middle-class business community and the UGTT (right). ….

A Liberalized Autocracy: While allowing for a measure of openness and competition, a liberalized autocracy ensures a hobbled pluralism, one that is ultimately limited by a very powerful president. In such a scenario, Saied would be the final arbiter of a political arena that would have just enough contending parties and groups to facilitate a strategy of divide and rule. Some electoral and ideological competition and inclusion would be necessary to play Islamists and secularists off of each other, or to set the rural population against the urban elite, or to encourage competition between the middle-class business community and the UGTT (right). ….

Saied possesses several assets that would help him build this system, adds Brumberg, an editorial board member of the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy:

- First, in addition to giving him nearly unsurpassed power, the constitution sets out an array of “freedoms,” the parameters of which are to be defined by the president via a subordinated parliament and judiciary.

- Second, the institutional, economic, and even legal materials needed to create these subordinated institutions are already available. By co-opting political elites, legal experts, and business leaders, Saied might indeed foster a measure of openness while retaining ultimate control.

- Third, the constitution’s provisions for a new regional assembly that is linked to local assemblies or people’s councils would give him an important tool to keep co-opted elites in line while simultaneously limiting the authority of the country’s parliament. …..RTWT

POMED

The United States can oppose Saied’s undemocratic actions by supporting Tunisia’s robust civil society, says Sabina Henneberg, author of Managing Transition: The First Post-Uprising Phase in Tunisia and Libya. Since 2011, civil society has played a key role in establishing human rights monitoring, promoting transparency initiatives, and otherwise building the country’s democratic practices. Over the past year, this sector has been instrumental in standing up to Saied, in part by organizing strikes and boycotts in response to his decrees, she writes for The Washington Institute.

A recent Arab Barometer poll (above) found falling public faith, including in Tunisia, in democracy as a motor for economic growth, adds VOA’s Bryant. Yet Ben Ali’s 2011 ouster, triggering the broader Arab Spring uprising, was fueled by the same bread-and-butter worries as today. Only now, things are worse.

However flawed and fragile, Tunisia’s democracy has “really, really mattered,” says Monica Marks, assistant professor of Middle East politics at New York University Abu Dhabi. “Tunisian democracy was a strong counter-argument not only to autocracies in the region but also violent extremists.”

– @WashInstitute https://t.co/JJMVUj4dID

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) August 9, 2022