Thousands gathered Monday in Tunisia’s capital as the country marked eight years since a democratic uprising ousted its long-time strongman. The rally came amid deepening economic troubles in the North African nation and resurgent anger at the revolution’s unfulfilled promises, Bouazza Ben Bouazza writes for The Washington Post:

Unions, political parties and other civil society groups came together in Tunis to celebrate the 2011 revolution and keep up pressure on the government to improve economic opportunity in the impoverished nation. State workers who want an end to a salary freeze plan a general strike Thursday that could disrupt airports, ports and the Mediterranean nation’s vital tourism industry. Union leader Mohamed Ali Boughdiri warned of possible violence, saying workers’ ”patience is running out.”

The country’s democratic experience is not “in a safe situation,” President Beji Caid Essebsi warned on Monday.

The country’s democratic experience is not “in a safe situation,” President Beji Caid Essebsi warned on Monday.

“We have adopted a democratic path and completed elections and a constitution,” explained the veteran Tunisian leader. “Despite the deficiencies in the constitution, it still distinguishes the Tunisian experience.”

Seven years on, one can dissect four main conflict issues that represent the main obstacles to democratic transition, analyst Lakhdar Ghettas argues in Open Democracy:

- the issue of the coalition of Nidaa Tounes and Ennahda;

- the nature of the political system, amid calls to review and amend the current hybrid semi-parliamentary / semi-presidential arrangements;

- the political role of the UGTT labour union; and

- the urgency of holding the local elections.

But there are other aspects of the transition that contribute to social unrest other than the economic hardship, including the work of the Truth and Dignity Commission.

The Tunisian story and revolution “is ultimately a Tunisian story and is not a regional Arab story,” said Truman Institute Senior Research Fellow Daniel Zisenwine (above). “’So many of the ingredients that worked in Tunisia’s favour, may, unfortunately, be absent in other countries. Tunisia is a relatively small population and it has a pretty strong tradition of political moderation and stability,” he adds.

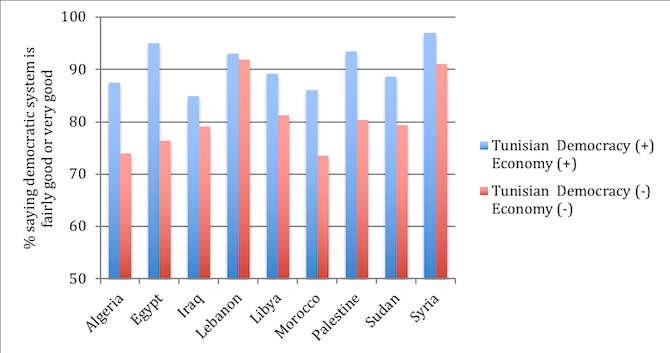

The economic performance of new democracies such as Tunisia is as important as the establishment of democratic practices during the transitional phase, research suggests. Democratic diffusion rests on the success of new democracies and economic success is indispensable to democratic success, according to A. Kadir Yildirim, a Middle East Fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, and Abdullah Aydogan, a lecturer of political methodology at Columbia University.

The economic performance of new democracies such as Tunisia is as important as the establishment of democratic practices during the transitional phase, research suggests. Democratic diffusion rests on the success of new democracies and economic success is indispensable to democratic success, according to A. Kadir Yildirim, a Middle East Fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, and Abdullah Aydogan, a lecturer of political methodology at Columbia University.

There are two major implications of their research findings, they write for the LSE’s Middle East Centre:

- On one hand, the success of a new democracy impacts upon public opinion vis-à-vis democracy in other countries in the region. It should also be noted that geographic proximity makes a difference. Countries that are geographically close to the successful example of democratisation will feel the democratic diffusion effect stronger than countries farther away. In this regard, the future of democracy in Tunisia might have a significant role in the future of democracy in the rest of the region. A possible future failure of the Tunisian experience may create a wave of dissatisfaction with democracy across the region, leading to notable levels of decrease in support for democracy.

- On the other hand, our results show that perceptions of democracy are contingent on economic performance. Survey respondents associated their evaluation of democratic governance with economic performance. When the economy performs well, respondents tend to associate positive views with democracy; otherwise, perceptions of democracy suffer. For a new democracy like Tunisia, economic performance can become the crucial yardstick with which citizens judge the merits of democracy. As public opinion surveys and more qualitative analysis previously have shown, lacklustre economic performance undermines trust in democratic institutions.

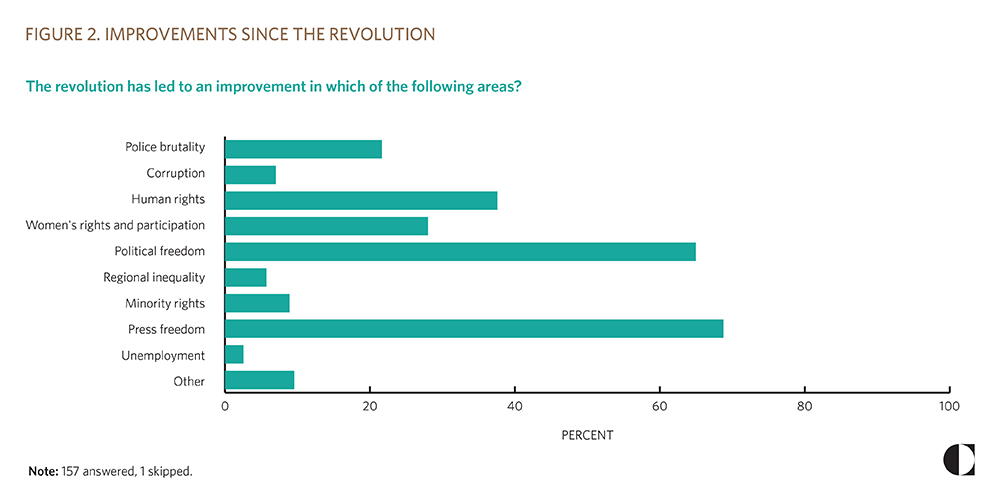

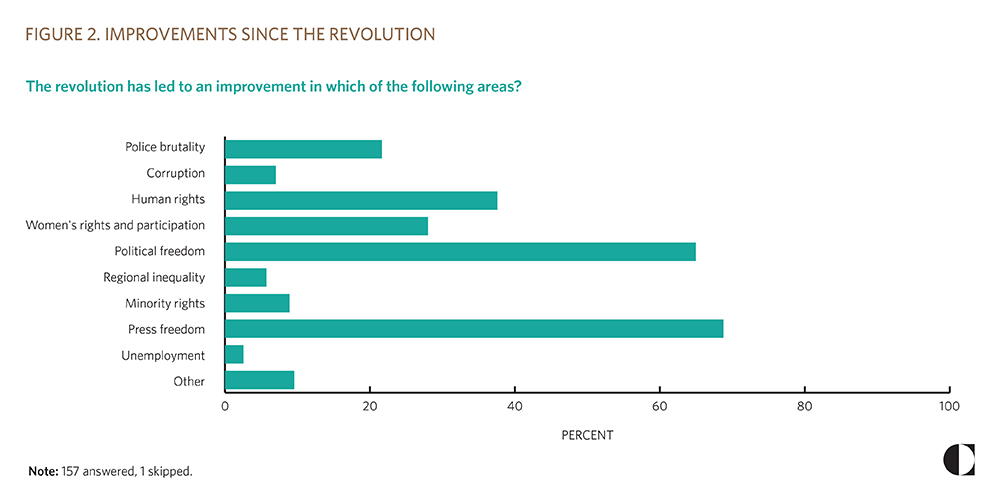

Credit: Carnegie Endowment

The socio-economic grievances that prompted the Jasmine Revolution have not been addressed, analysts argue.

“What can be described as a dramatic transformation at the political level has not translated into economic and social gains for the majority,” said Larbi Sadiki, a professor of political science at Qatar University. “The shift from popular uprising to institutional politics has not been smooth and has benefited the few, various cliques, often at the expense of the immediate interests of citizens throughout Tunisia’s various regions.”

“Today, eight years after the success of the revolution of freedom and dignity, despite all difficulties and dangers, the Tunisian exception still stands,” said Rached Ghannouchi, leader of the moderate Islamist Ennahda party, which is part of Tunisia’s governing coalition. “Nevertheless, the magnitude of the political gains made does not make Tunisians blind to the pressing need to complete the achievement of the social, economic and developmental aims of the revolution, nor to the challenges still facing our country.”

“There is no alternative to consensual politics according to electoral law,” Ennahda’s Ghannouchi added. “Tunisia’s winning card is the success of its democratic transition. We should not lose this card.”

Tunisia is at a critical inflection point, particularly as the country approaches the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections, according to Sarah Yerkes and Zeineb Ben Yahmed, analysts in Carnegie’s Middle East Program. All actors—from civil society activists to politicians to international donors to the private sector—have an opportunity to address the economic and social challenges that inspired the 2010–2011 revolution and persist eight years later, they add:

Tunisia is at a critical inflection point, particularly as the country approaches the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections, according to Sarah Yerkes and Zeineb Ben Yahmed, analysts in Carnegie’s Middle East Program. All actors—from civil society activists to politicians to international donors to the private sector—have an opportunity to address the economic and social challenges that inspired the 2010–2011 revolution and persist eight years later, they add:

As one Tunisian civil society actor noted, “we cannot go back or retreat.” But failure to create substantial new jobs, particularly for the educated youth, and to narrow the gap between the coastal and interior regions has the potential to undo the country’s positive political progress.

Tunisia had a critical advantage over other Arab States that failed to generate a democratic process following the Arab Spring protests.

“Civil society was well established in Tunisia, even though they had human rights organizations,” said Arnaud Kruze, a Woodrow Wilson Center global fellow (above). “It gave society and population of Tunisia a network of actors that were then crucial at the time of transitioning the country into safer water and democratize.”

Tunisia’s democracy “has shown remarkable resilience in the face of political, security, economic, and regional challenges,” said the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED). “Tunisians have created a genuinely pluralistic political system, held multiple free and fair elections, completed several peaceful transfers of power, enacted a new constitution and laws enshrining freedoms, and built an inspired and resourceful civil society that has safeguarded the democratic transition at several critical points,” it observed.

Tunisia’s democracy “has shown remarkable resilience in the face of political, security, economic, and regional challenges,” said the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED). “Tunisians have created a genuinely pluralistic political system, held multiple free and fair elections, completed several peaceful transfers of power, enacted a new constitution and laws enshrining freedoms, and built an inspired and resourceful civil society that has safeguarded the democratic transition at several critical points,” it observed.

“But there is much work left to be done, and 2019 will be a crucial year in determining the fate of Tunisia’s transition,” added POMED, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy:

- Economic opportunity and social justice should be accessible to all Tunisians.

- A comprehensive and serious effort to combat corruption should be launched.

- Security forces need to be held accountable for discriminatory and abusive behavior, including for torture.

- Although the mandate of the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD) ended last month, far more work is required to bring justice to the dictatorship’s victims and to create new systems of accountability.

- The long-delayed Constitutional Court, along with other constitutionally mandated institutions designed to guarantee newfound freedoms, needs to be established.

- Civil society must remain vigilant against attempts to restrict freedom of association.

- The Tunisian government should take immediate steps to strengthen the Independent High Authority for Elections (ISIE) and ensure its autonomy so that credible, free, and fair parliamentary and presidential elections can take place before the end of 2019 as scheduled.

Foreign influence is another destabilizing factor, adds Tunis-based analyst Youssef Cherif, a member of the Carnegie Civic Research Network and head of Columbia Global Centers Tunis. Today, Tunisia is a geopolitical battlefield for regional powers like Egypt, Turkey, and the Gulf states, and Tunisian politicians occasionally take sides to suit their suitors’ goals. Broadly speaking, Saudi Arabia and the UAE demonize Tunisia’s democracy and Ennahda, while Qatar and Turkey laud both. Both camps have their clients in the country. These players amplify coup rumors and delegitimize Tunisia’s political independence, which adds to the public’s distrust of the government, he writes for Project Syndicate.

The 2017-2018 Arab Opinion survey shows that public opinion towards the Arab Spring has worsened over time, reports suggest. In the most recent survey, 34 percent of Arabs believed that the Arab Spring had been aborted before the revolutions could achieve their aims, and that the former regimes have returned to power. This is a marked decline from 2014, when two-thirds of the Arab public was openly optimistic about the possibility of the Arab Spring achieving its aims.

Many still look to Tunisia as a potential model for a successful democratic transition, even as they recognize that it remains a fragile experiment. But as Tunisians mark the occasion this year, it is becoming apparent that the abuses that led to the revolution are being forgotten, Fadil Aliriza writes for The Post:

It’s not that Tunisians haven’t tried to investigate the past. In 2013, legislators passed a law setting up a transitional justice process aimed at exposing human rights abuses by the government and assigning responsibility for abuses, to seek redress and ultimately reconciliation. In 2014, the government established the Truth and Dignity Commission to carry out this process. Like in so many other truth commissions, such as in South Africa and Chile, its work throughout has fallen short of victims’ expectations.

Tunisia’s allies in the international community need to continue focusing on countering corruption and ensuring that this features prominently in foreign assistance, Ambassador Daniel H. Rubinstein tells Carnegie’s Sarah Yerkes.