There’s a fundamental flaw in the Russian propaganda narrative about the poisoning of former double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in the U.K. earlier this month, Bloomberg’s Leonid Bershidsky writes: It assumes that Western nations want to gang up on Russia and punish it regardless of whether there’s any evidence linking it to the assassination attempt. In reality, the Western response to the incident shows how reluctant European nations are to escalate tensions with Russia.

There’s a fundamental flaw in the Russian propaganda narrative about the poisoning of former double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in the U.K. earlier this month, Bloomberg’s Leonid Bershidsky writes: It assumes that Western nations want to gang up on Russia and punish it regardless of whether there’s any evidence linking it to the assassination attempt. In reality, the Western response to the incident shows how reluctant European nations are to escalate tensions with Russia.

The unified international response to the Skripal poisoning shows that the West will only suffer so much provocation, says analyst Mark Galleotti. This new determination from the West to take Putin to task is the product of a cumulative process, he writes for the Atlantic.

The unified international response to the Skripal poisoning shows that the West will only suffer so much provocation, says analyst Mark Galleotti. This new determination from the West to take Putin to task is the product of a cumulative process, he writes for the Atlantic.

But German politicians from the left and right have criticised the government’s decision to expel four Russian diplomats over the nerve agent attack, saying there was still no conclusive proof that Russia was behind the poisoning, the FT adds:

Jürgen Trittin, the German Greens’ foreign policy expert, said it was “reckless to act against Russia in this way, and stumble into a new cold war without solid evidence and only on the basis of certain clues”.

“If this is continued, then we will very quickly find ourselves in a Cold War 2.0 situation, and I do not think this is wise,” he added. “For everything we want from Russia and where we want Russia to change its behavior — be it Syria or the stationing of medium-range missiles — a new Cold War is not helpful, but possibly even harmful.”

“If this is continued, then we will very quickly find ourselves in a Cold War 2.0 situation, and I do not think this is wise,” he added. “For everything we want from Russia and where we want Russia to change its behavior — be it Syria or the stationing of medium-range missiles — a new Cold War is not helpful, but possibly even harmful.”

The West and Russia may be on the brink of a new Cold War, some analysts suggest.

“I don’t think many of us would question that we do face a new Cold War,” said Dimitri Simes, Center for the National Interest president and chief executive officer.

“Now a new Cold War might be different in many respects than the old one,” he added. “First of all, a very different balance of forces. Second, the absence of an attractive international ideology on the Russian side. Third, obviously, Russia is much more exposed to the West than during the original Cold War, but also, fewer rules and, I think, perhaps more emotions on both sides and increasingly hostile emotions on both sides.”

There have also been comparisons made between the poisoning of a former Russian spy and Soviet behavior during the Cold War, the BBC adds.

There have also been comparisons made between the poisoning of a former Russian spy and Soviet behavior during the Cold War, the BBC adds.

“The Soviet Union clearly did try and kill people abroad who they didn’t like,” says Michael Cox, Emeritus Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics. “So it isn’t that Russia is doing anything novel in that regard.”

The volatile state of Russia’s relations with the outside world today, exacerbated by a nerve agent attack on a former spy living in Britain, however, makes the diplomatic climate of the Cold War look reassuring, said Ivan I. Kurilla, an expert on Russian-American relations, and recalls a period of paralyzing mistrust that followed the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

“If you look for similarities with what is happening, it is not the Cold War that can explain events but Russia’s first revolutionary regime,” which regularly assassinated opponents abroad, said Mr. Kurilla, a historian at the European University at St. Petersburg.

He told the New York Times that Russia’s president, Vladimir V. Putin, had no interest in spreading a new ideology and fomenting world revolution, unlike the early Bolsheviks, but that Russia under Mr. Putin had “become a revolutionary regime in terms of international relations.”

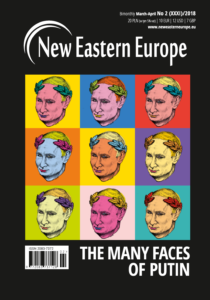

The Kremlin has a dual agenda: to mobilize anti-western sentiment in Russian society, while at the same time engaging with the west and persuading the liberal democracies to co-operate with it, analyst Lilia Shevtsova (left), a Reagan-Fascell fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy, writes for the Financial Times:

The Kremlin has a dual agenda: to mobilize anti-western sentiment in Russian society, while at the same time engaging with the west and persuading the liberal democracies to co-operate with it, analyst Lilia Shevtsova (left), a Reagan-Fascell fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy, writes for the Financial Times:

Great power status and the desire for external domination have long been central components of the Russian system of personalised power. But building a galaxy of satellite states, as the Soviet Union did, is no longer the only way Russia seeks such status. With diminishing resources, the Kremlin has increasingly resorted to intimidating the world’s liberal democracies into accepting Russia’s grand ambitions.

Tensions between the West and Russia are likely to escalate, at least in the short term, in what could look like a “Cold War on steroids,” Nina Khrushcheva, who is the granddaughter of the former Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, and who now teaches at the New School, in New York, told the New Yorker’s Robin Wright.

“Putin is judo-esque to the core of his being. For him, this is all a game: ‘Who’s he going to screw next?’ He wants the upper hand. He doesn’t give up. He doesn’t stand back. He sees an opening and strikes. He punches ten times what he receives. He’s a brilliant tactician but a petty man. We’ve seen that for all his eighteen years in power.”

“Putin is judo-esque to the core of his being. For him, this is all a game: ‘Who’s he going to screw next?’ He wants the upper hand. He doesn’t give up. He doesn’t stand back. He sees an opening and strikes. He punches ten times what he receives. He’s a brilliant tactician but a petty man. We’ve seen that for all his eighteen years in power.”

Britain, but also other countries, have built up a dependence on Russia, be it oligarchs parking their money in London or Germany increasing its energy dependence on Russia by building another Nord Stream gas pipeline, notes Carnegie analyst Judy Dempsey. Both make a mockery of solidarity. Both run counter to resilience.

“Moscow will now try to divide the EU into two camps – the radical pro-British camp and those who they would think followed the EU because of the demands for solidarity rather than out of conviction,” said Konstantin Eggert, a Russian analyst and journalist.

In his opinion, the UK will also gradually escalate its measures against Russia.

“It is quite conceivable to me that quite soon there will be a British version of the Magnitsky Law and it seems that the desire to clamp down on Russian wealth in the UK is the most serious of all others over the last 15-17 years,” he told Al Jazeera.

“It is quite conceivable to me that quite soon there will be a British version of the Magnitsky Law and it seems that the desire to clamp down on Russian wealth in the UK is the most serious of all others over the last 15-17 years,” he told Al Jazeera.

These are aspects of how the Cold War created the world we live in now, notes Harvard’s Odd Arne Westad. But today’s international affairs have moved beyond the Cold War, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

- Bipolarity is gone. If there is any direction in international politics today, it is toward multipolarity. The United States is getting less powerful in international affairs. China is getting more powerful. Europe is stagnant. Russia is a dissatisfied scavenger on the fringes of the current order. But other big countries such as India and Brazil are growing increasingly influential within their regions.

Ideology is no longer the main determinant. China, Europe, India, Russia, and the United States disagree on many things, but not on the value of capitalism and markets. China and Russia are both authoritarian states that pretend to have representative governments. But neither is out to peddle their system to faraway places, as they did during the Cold War. Even the United States, the master promoter of political values, seems less likely to do so under Trump’s “America first” agenda.

Ideology is no longer the main determinant. China, Europe, India, Russia, and the United States disagree on many things, but not on the value of capitalism and markets. China and Russia are both authoritarian states that pretend to have representative governments. But neither is out to peddle their system to faraway places, as they did during the Cold War. Even the United States, the master promoter of political values, seems less likely to do so under Trump’s “America first” agenda.

- Nationalism is also on the rise. Having had a hard time reasserting itself after the ravages of two nationalist-fueled world wars and a Cold War that emphasized non-national ideologies, all great powers are now stressing identity and national interest as main features of international affairs. Cold War internationalists claimed that the national category would matter less and less. The post–Cold War era has proven them wrong. Nationalists have thrived on the wreckage of ideology-infused grand schemes for the betterment of humankind.