Credit: NDI

Some observers have argued that election “meddling” by Russia and other authoritarian regimes is acceptable because “everyone does it,” drawing a false comparison with democracy assistance. But advancing democracy has absolutely nothing in common with cyber-hacking and disinformation by authoritarian regimes, who are afraid to hold legitimate elections at home, the National Democratic Institute* notes:

- Authoritarian countries refuse to hold legitimate elections at home, and undermine open election processes abroad for their own strategic purposes. Domestically, opposition political leaders are harassed or assassinated and opposition parties are de-legitimized and frequently barred from the ballot. Independent media is muzzled. Civil society groups seeking to monitor election processes are shut down and persecuted, and, in some cases, their leaders are imprisoned. Voters are denied the right to express their free will and the results are predetermined. Elections are held in name only.

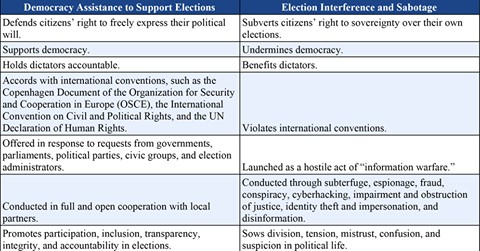

By contrast, election assistance is a response to requests from governments, parliaments, political parties, civic groups, and election administrators to promote transparency, participation and accountability. It gives voice to people who are excluded. The election work of democracy assistance organizations that closely adhere to international standards simply cannot be compared to the actions of autocrats who hold illegitimate elections at home and hack and disrupt democratic elections abroad. The chart below outlines these fundamental differences.

By contrast, election assistance is a response to requests from governments, parliaments, political parties, civic groups, and election administrators to promote transparency, participation and accountability. It gives voice to people who are excluded. The election work of democracy assistance organizations that closely adhere to international standards simply cannot be compared to the actions of autocrats who hold illegitimate elections at home and hack and disrupt democratic elections abroad. The chart below outlines these fundamental differences.

The argument finds support from the leading analyst of democracy assistance.

The U.S. response to Russian meddling in the 2016 election has been extraordinarily weak, notes Thomas Carothers, the Carnegie Endowment’s Senior Vice President for Studies. Not only that, it has been accompanied by an attitude of “whataboutism” on the part of some Americans—the relativistic view that the United States has little ground to complain about Russia’s actions given its own history of meddling in other countries’ political campaigns and elections, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

It is certainly essential to be honest and realistic about the considerable record of past U.S. electoral meddling, and the contrast between Russia and the United States in this domain is certainly not black and white. Yet neither is it one of indistinguishable shades of gray. The United States is simply not engaging in electoral meddling in a manner comparable to Russia’s approach.

Two key flaws underlie relativist accounts, Carothers adds:

Two key flaws underlie relativist accounts, Carothers adds:

- First, such a position fails to distinguish adequately between the pattern of U.S. interventionism during the Cold War, on the one hand, and U.S. activity since the end of the Cold War on the other. During the former period, the United States did indeed illegitimately intervene in numerous foreign elections, trying to tilt outcomes in favor of candidates the United States preferred and in a smaller number of cases laboring to oust legitimately elected leaders Washington saw as hostile to its security and economic interests. …Since the end of the Cold War, however, such interventionism has decreased significantly because U.S. policymakers no longer view the world as enmeshed in a global ideological struggle in which every country, no matter how small, is a critical piece on a larger strategic chessboard. Washington has thus become much less concerned about the outcomes of most foreign elections and much less engaged in trying to tilt them in any particular direction…..

- A second problematic element of the relativist position is the charge that U.S. efforts to promote democracy abroad—which make use of diplomatic leverage, democracy aid, and cooperation with pro-democratic multilateral organizations—are just another, more covert form of electoral meddling akin to what the Russians are doing. ….U.S. pro-democracy diplomacy and assistance do indeed seek to shape the political direction of other countries. And they are carried out with a strong sense of self-interest, not out of unalloyed idealism. They are driven by the belief that democratic outcomes abroad will generally be favorable to U.S. security and economic interests by producing stable governments amenable to deeper partnerships thanks to shared political values.

“But unlike Russian electoral meddling, U.S. democracy promotion does not seek to exacerbate sociopolitical divisions, systematically spread lies, favor particular candidates, or undercut the technical integrity of elections,” Carothers notes. “On the whole, it seeks to help citizens exercise their basic political and civil rights in electoral processes, enhance the technical integrity of such processes, and increase electoral transparency.”

*A core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy.