Chad’s interim Foreign Affairs Minister Cherif Mahamat Zene said on Monday he was stepping down because of disagreements with senior politicians, as the government attempts to open dialogue with rebels and end military rule, Reuters reports. Zene resigned as talks are taking place in Qatar’s capital Doha with various rebel and opposition groups aimed at paving the way to elections after the military seized power last year.

Valéry Nadjibe, the National Endowment for Democracy’s Program Officer for Central Africa discussed the ongoing National Dialogue in Chad on Voice of America (VOA)’s Washington Forum (above).

Despite the rise of more sophisticated strategies of election rigging and censorship, an increasing number of African countries have seen a transfer of power, note analysts Marie-Eve Desrosiers and Nic Cheeseman. Even in places where governments remain undefeated, such as Namibia and South Africa, the gap between the ruling party and the opposition has narrowed considerably. The message for ruling parties is clear: perform poorly in the context of economic decline, and you are operating on borrowed time.

Despite the rise of more sophisticated strategies of election rigging and censorship, an increasing number of African countries have seen a transfer of power, note analysts Marie-Eve Desrosiers and Nic Cheeseman. Even in places where governments remain undefeated, such as Namibia and South Africa, the gap between the ruling party and the opposition has narrowed considerably. The message for ruling parties is clear: perform poorly in the context of economic decline, and you are operating on borrowed time.

Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Liberia and Sierra Leone all go to the polls in 2023, and governments, opposition parties and civil society groups are all wondering what these trends mean for them. So why are opposition parties on the rise, which governments are most vulnerable to losing power, and what determines whether the ruling party can avoid electoral defeat? they ask in Africa Report:

- First, opposition leaders are getting better at their craft. In Gambia (2016) and Malawi (2020) the defeat of the government was made possible by the formation of broad and effective coalitions, ensuring that unpopular leaders could not retain power by dividing the opposition. In Kenya, Ruto benefited from experience of both winning and losing elections as part of other leaders’ campaigns and correctly divined that the power of the “Big Man” politics for which Kenya is well known had waned. Instead, he focused on bringing in lower level leaders who could deliver constituencies and counties….

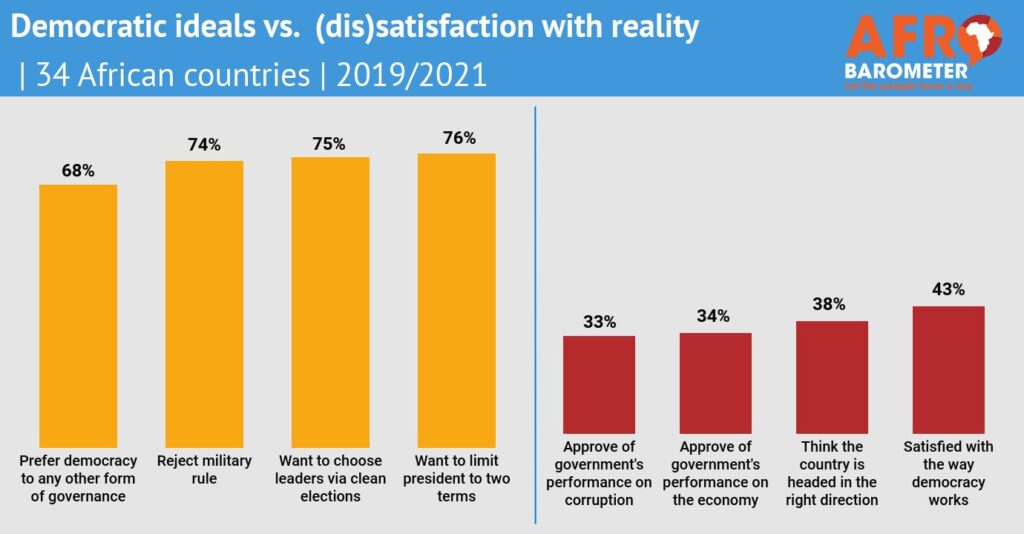

- Second, increasingly well-educated electorates with considerable experience of multiparty politics – after thirty years of going to the polls – are increasingly frustrated with poorly performing governments. While support for democratic government has remained robust in the last ten years, satisfaction with how democracy is performing has declined, and there is a growing recognition of the impact of corruption on public services and the lives of citizens.

- These changes have been significant, but their impact would not have been transformational if they hadn’t taken place in the context of severe economic challenges. Falling employment and eroded savings during the pandemic have been followed by rising prices, causing real pain for citizens. This third trend, and the difficulty that governments face in sustaining living standards, has given public criticism of corruption greater bite and blown wind into the sails of opposition leaders.

Africans are supportive of democratic ideals, but often disillusioned with the political reality. Credit: Afrobarometer.

The challenge that these shifts represent for ruling parties in Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Zimbabwe is brought home by recent research conducted by Cheeseman with Anne Pitcher and Peter Penar, they add. That analysis, based on Afrobarometer survey data from 33 countries, finds that support for opposition parties in Africa tends to be higher when citizens believe that the economy is badly managed, are less satisfied with public services, and inflation is lower.

This means that ruling parties cannot afford to underperform – neither ethnicity, patrimonialism, nor clientelism will insulate governments from future electoral defeat, Desrosiers and Cheeseman conclude. RTWT