For all of the rhetoric about democracies versus autocracies being the defining challenge of our times, if democracies are in trouble, autocracies may be the least of their problems, a leading analyst observes.

Why? Because the evidence is mounting that Russia, whose fortunes in Ukraine are declining, and China, in deep economic trouble and facing a global backlash to leader Xi Jinping’s aggressive foreign policy, are not as strong as they once seemed, according to the Stimson Center’s Robert A. Manning, a former member of the U.S. secretary of state’s policy planning staff and the National Intelligence Council Strategic Futures Group.

In both cases, the lack of accountability and corruption inherent in autocratic systems threatens to turn seriously flawed policies closely identified personally with both Russian President Vladimir Putin and Xi, respectively, into disastrous outcomes, he writes for The Hill.

If democracies are in trouble, autocracies may be the least of their problems, @StimsonCenter‘s @Rmanning4 writes for @thehill https://t.co/jU1OZLdh1j

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) September 20, 2022

The State Department deserves much credit for achieving NATO unity, states analyst Robert D. Kaplan. Nevertheless, stressing that this is a “battle between democracy and autocracy,” rather than framing it as a rules-based international order versus the law of the jungle, is an error. For one thing, that approach has robbed the US of allies in the developing world that are not democracies, but might still oppose Russian aggression, he writes for Bloomberg:

Putting an emphasis on a rules-based order wouldn’t mean that the US doesn’t support democracy, only that Russia’s violation of international norms has been so vast and flagrant that the world beyond the community of democracies can unite against it. The elder Bush’s secretary of state, James Baker III, forged a coalition of 35 nations, democracies and autocracies both, to eject Iraqi forces from Kuwait in 1991.

It’s the culture, stupid

Ukraine’s societal mobilisation and cohesion have paid off throughout the conflict, another expert notes. By focusing on military hardware, experts often miss the “software” of war: the quality of leadership, morale and motivation, decision-making and governance and the engagement of society, adds Orysia Lutsevych, head of Chatham House’s Ukraine Forum.

Ukraine’s societal mobilisation and cohesion have paid off throughout the conflict, another expert notes. By focusing on military hardware, experts often miss the “software” of war: the quality of leadership, morale and motivation, decision-making and governance and the engagement of society, adds Orysia Lutsevych, head of Chatham House’s Ukraine Forum.

War is an expression of political culture on the battlefield, she writes for The Guardian. And there are stark differences between Ukrainian and Russian culture. Many in the west mistakenly thought Ukraine was just like Russia, but weaker, more corrupt and chaotic. In fact, while Ukraine is by no means perfect, it is more agile and decentralised, compared to the autocratic and rigid Russian state.

Moreover, many in the west have underestimated the basic intellectual and combat capacity of Ukraine’s forces, Lutsevych notes, citing a new crowdsourcing intelligence tool that allows Ukrainians to report Russian collaborators and saboteurs instantly and anonymously.

The Institute for the Study of War, a Washington-based think tank, said the call by the Russian proxy leaders for Moscow to “immediately” annex the territories reflected panic and was “incoherent” since it would “place the Kremlin in the strange position of demanding that Ukrainian forces unoccupy ‘Russian’ territory, and the humiliating position of being unable to enforce that demand,” The Times reports.

Iuliia Mendel, former Press Secretary to Ukrainian President Zelenskyy and author of “The Fight For Our Lives: My Time with Zelenskyy, Ukraine’s Battle for Democracy, and What It Means for the World” tells MSNBC’s Nicolle Wallace why Ukraine will win (above).

Iuliia Mendel, former Press Secretary to Ukrainian President Zelenskyy and author of “The Fight For Our Lives: My Time with Zelenskyy, Ukraine’s Battle for Democracy, and What It Means for the World” tells MSNBC’s Nicolle Wallace why Ukraine will win (above).

Putin’s misadventure in Ukraine is exposing the limits to autocratic solidarity, says a leading observer.

Xi Jinping probably regrets his commitment to a “partnership without limits” with Putin, if only because the Chinese president himself has drawn some exceedingly firm limits on granting symbolic rather than material help to Beijing’s “partner in need.” Xi does not want to see Russia’s defeat and Putin’s inglorious exit, but he neither fancies to ally with a loser nor anchor China to a sinking ship, notes Jamestown’s Pavel Baev.

Credit: Princeton UP

According to Dmitry Savvin, editor of the conservative Russian Harbin portal, a genuine anti-Putin underground may now be emerging, Paul Goble reports. But before anyone in the emigration decides whether it is genuine or only an FSB plot, many more questions need to be answered about what is actually happening in Russia and who is behind these actions, he reasonably suggests.

Exiled Russian opposition activist Ilya Ponomarev believes that “we should not try to slow-down those who have had enough and are ready to take actions into their own hands to bring Putin’s 22 years in power to a hard stop.”

“If we really want to support Ukraine, we need to look beyond the military victory that Ukraine will surely obtain. We need to examine how it is that we can be sure that Putin does not start a new invasion, again, a few years down the road,” he told a recent meeting in Washington (below). “We need to be frank in recognizing that Russia will remain a pariah as long as Putin rules – so how can be bring an end to the Putin era and make him face justice for his crimes?”

Leaving aside the immense political and economic costs, the Kremlin could use a victory in Ukraine to try and reassert its influence in the post-Soviet sphere, says Carnegie Europe’s Judy Dempsey. And other authoritarian leaders could be emboldened by Russia’s so-called achievements. In Russia itself, a victory would deal a devastating blow to the pockets of civil society and small opposition to the war, while the Kremlin’s authoritarianism could gain further momentum.

Moscow and Beijing are having success spreading disinformation about the Ukraine war in the global south, notes Johns Hopkins University’s Hal Brands, author of The Twilight Struggle….. And yet….

Moscow and Beijing are having success spreading disinformation about the Ukraine war in the global south, notes Johns Hopkins University’s Hal Brands, author of The Twilight Struggle….. And yet….

Globally, around two-thirds of countries support Ukraine. However, this does not mean they are willing to back sanctions on, or even multilateral declarations condemning, Russia, notes analyst Anna Diamantopoulou. For instance, the BRICS states invited 12 other countries to their recent summit. China used the opportunity to call on them to unite in support of one another’s fundamental interests. Given the internal strains on liberal democracy this sort of effort could harm democracy’s normative standing in the global arena even more.

Against this background, the Western alliance now faces three major challenges that will shape the new cold war: external alliances, the unity of the European Union, and people power, she writes for the European Council on Foreign Relations:

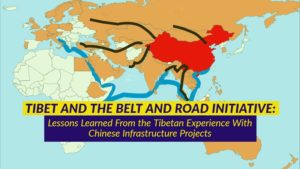

External alliances: Most Latin American, African, and Asian states are far less interested in the West’s efforts to uphold a rules-based order than in transactional relationships that could help them deal with domestic problems….. Mobilising funds that can practically rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative and channel them in a strategic way throughout Africa and Asia is a challenge itself, as it would require enhanced consensus among EU member states. However, the EU’s Global Gateway infrastructure investment programme, if implemented quickly and efficiently, would be a geopolitically significant project for EU engagement with external actors.

External alliances: Most Latin American, African, and Asian states are far less interested in the West’s efforts to uphold a rules-based order than in transactional relationships that could help them deal with domestic problems….. Mobilising funds that can practically rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative and channel them in a strategic way throughout Africa and Asia is a challenge itself, as it would require enhanced consensus among EU member states. However, the EU’s Global Gateway infrastructure investment programme, if implemented quickly and efficiently, would be a geopolitically significant project for EU engagement with external actors.- EU unity: Recent statements by various EU and NATO leaders suggest significant differences between them on the question of peace negotiations between Russia and Ukraine. Crucially, NATO member Turkey has engaged in behaviour similar to Russia’s – invading and annexing the territory of independent countries (Cyprus and Syria), calling into question its border with a neighbouring state (Greece), shifting towards authoritarianism, and committing widespread human rights violations at home….. The EU should acknowledge that the assertiveness of Turkish foreign policy is a challenge to regional stability and adjust its Turkey policy accordingly…

People power: Many Western countries will soon hold elections against the backdrop of multiple crises. Most of their citizens want to support Ukraine, but they are also weary of long-running economic and public health problems, as well as the widespread sense of insecurity in Europe. All this could affect their attitudes towards the new cold war and solidarity within the Western alliance…..

People power: Many Western countries will soon hold elections against the backdrop of multiple crises. Most of their citizens want to support Ukraine, but they are also weary of long-running economic and public health problems, as well as the widespread sense of insecurity in Europe. All this could affect their attitudes towards the new cold war and solidarity within the Western alliance…..

In the long run, democracy is the most powerful and effective governance system available. But, in the coming months, Western states will have work to do if they are to convince their partners elsewhere in the world of this fact, Diamantopoulou adds. If the West wants to convince of the power of its governance system, it should first fix its problems and then create an exportable grand narrative.