Autocracies consume an increasing proportion of official development assistance (ODA) flows, from 64% in 2010 to 79% in 2019, according to a recent OECD analysis. There are

two reasons for this, it suggests:

- First, the number of electoral autocracies increased from 52 to 57.

- Second, higher volumes of ODA were disbursed to closed autocracies, with a striking 19-fold increase of humanitarian aid to closed autocracies.

In 2019, 79% of the population in the 124 ODA recipient countries and territories lived under an autocratic regime (up from 56% in 2010).

Funding autocracy has become the new normal in development aid, analyst Brian Klaas tweeted.

“ODA demonstrates a consistent pattern in responding to countries that democratize: they were generally rewarded with an increase in ODA, including more governance support,’ the OECD report adds. But the study notes a strong (193%) increase in state building support to closed autocracies.

“ODA demonstrates a consistent pattern in responding to countries that democratize: they were generally rewarded with an increase in ODA, including more governance support,’ the OECD report adds. But the study notes a strong (193%) increase in state building support to closed autocracies.

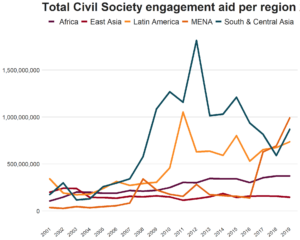

Such aid to autocratic regimes seems at odds with the OECD’s official commitment to empowering civil society actors as “critical contributors” to inclusive societies, accountable institutions, and to strengthening democracy.

There can be good reasons to spend development assistance in autocracies especially if that support makes them less autocratic and saves lives, but the results of that seem questionable, argues James Deane, Head of Policy at BBC Media Action and co-founder of the International Fund for Public Interest Media. Given how effective independent media is at holding power to account, at least doubling or tripling the existing very small volumes of support to media assistance in this context seems more than justified, he writes for the London-based Foreign Policy Centre.

European donors increased their aid in 2021, which they insisted increased the resources made available for democracy projects, a recent Carnegie study observed, although without specific or identifiable amounts being allocated to democracy assistance it was impossible to quantify the measure of their commitments.

European donors increased their aid in 2021, which they insisted increased the resources made available for democracy projects, a recent Carnegie study observed, although without specific or identifiable amounts being allocated to democracy assistance it was impossible to quantify the measure of their commitments.

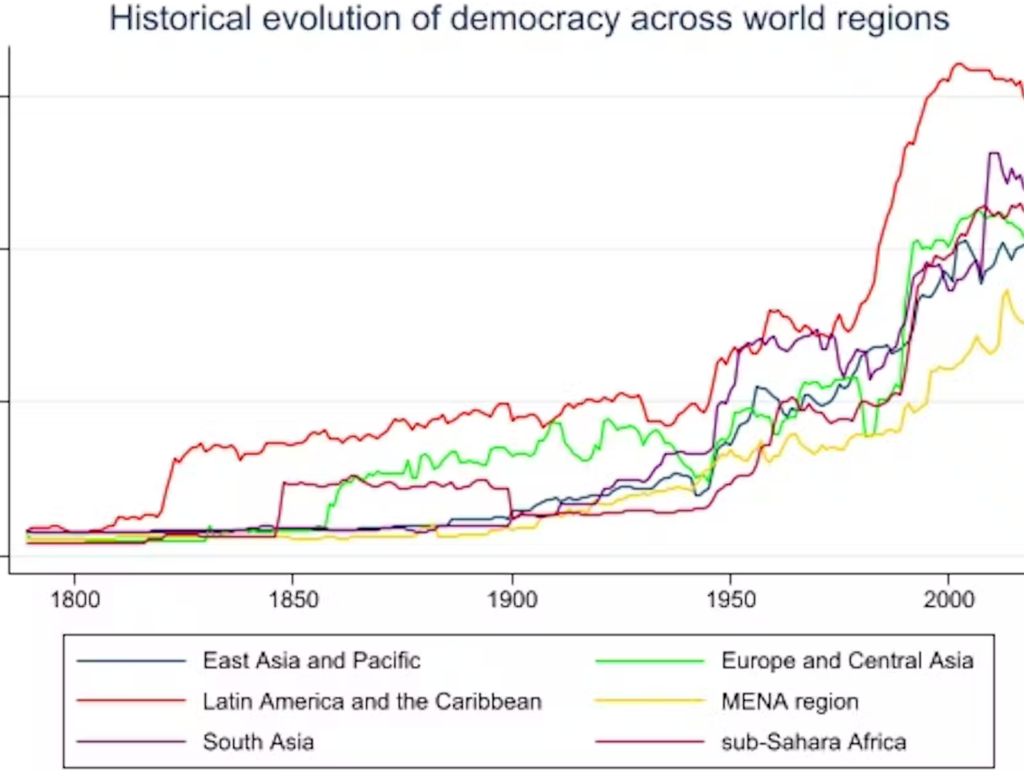

Although Western donors allocate billions of dollars each year to democracy assistance, the role of such assistance in democratization remains contested, notes a recent study of EU-led democracy assistance projects across 126 recipient countries. Using from the OECD and the Varieties of Democracy Institute to capture democracy levels, it finds that EU’s democracy assistance positively impacts democracy levels of recipient countries, especially coupled with political conditionality and monitoring mechanisms in beneficiary countries, Adea Gafuri writes for Democratization.

The once relatively separate communities of democracy aid and development aid have in recent years become increasingly interconnected as developmentalists acknowledge the importance of taking politics into account and accept governance as a factor in developmental success, experts told a Carnegie-Journal of Democracy symposium (above).

- Aid specifically aimed at improving democratic infrastructure and institutions has a modest but positive impact overall. This impact is clearer than for the impact of development aid generally, but there is no evidence that either has a negative impact on democracy on average.

- Aid aimed at supporting civil society, media freedom, and human rights seems to be the most effective in terms of its impact on democracy.

- Aid is more effective at supporting ongoing democratisation than at halting democratic backsliding.

Under the Biden administration, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is reviewing existing policy and drafting a new strategy to help guide an affirmative response to the challenges posed by the PRC, a recent CSIS analysis observed:

In competing with China—and Russia to a lesser extent—the Biden administration will also contend with broader international challenges such as the Covid-19 pandemic, rising authoritarianism, and climate change. The Biden administration’s Interim National Security Guidance captures this dynamic: “China, in particular, . . . is the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system.”

Foreign aid can help stem the decline of democracy, if used in the right way https://t.co/FyezHtQusr via @ConversationUK

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) August 29, 2022

The evidence shown in the OECD report raises some questions for policy making and operations that require further reflection and discussion. These include:

1. How can the DAC identify and respond to democratic backsliding? What are possible early warning signs and responses?

2. How can the DAC better identify and respond to democratic windows of opportunity? What are the opportunities to further democratic consolidation?

3. To what extent are DAC members equipped to respond effectively to sudden regime changes?

4. To what extent might ODA to governance be better tailored to different regime contexts?

5. How can the DAC better engage with non-DAC members on issues related to autocratisation and democratisation?

6. To what extent can ODA work to enable more effective, inclusive and accountable governments, even in autocratic contexts?

7. How can DAC members continue to respond to the needs of the poor, vulnerable and

disadvantaged in autocratic contexts, without reinforcing these regimes?

8. How can the DAC better balance state building and democracy promotion to ensure the

effectiveness of governance support? RTWT