Credit: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

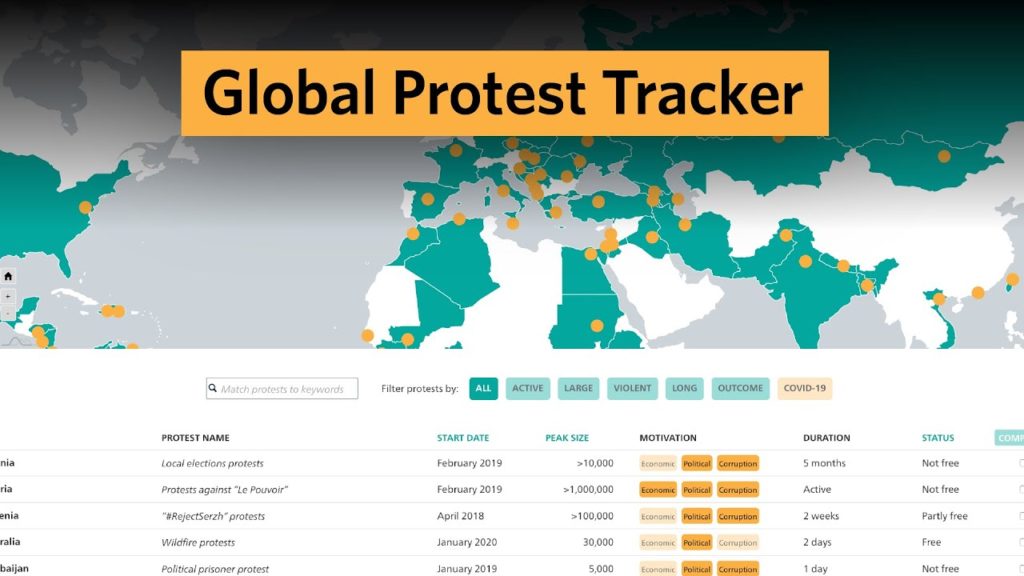

People power, which democratized countries from South Korea and Poland in the 1980s to Georgia and Ukraine in the 2000s and Tunisia in 2010, has been on a losing streak. That’s true even though mass protests proliferated in countries around the world last year and have continued in a few places during 2020 despite the pandemic, The Washington Post’s Jackson Diehl observes.

According to Stanford political scientist Larry Diamond (right), there have been 20 instances since 2009 in which autocratic governments were challenged either by mass protests or an unexpected electoral defeat. In only two — Tunisia in 2011 and Ukraine in 2014 — was there a transition to democracy. Why doesn’t people power work like it used to? He cites a couple of big factors in Democratic regression in comparative perspective: scope, methods, and causes, an article for Democratization, Diehl adds:

According to Stanford political scientist Larry Diamond (right), there have been 20 instances since 2009 in which autocratic governments were challenged either by mass protests or an unexpected electoral defeat. In only two — Tunisia in 2011 and Ukraine in 2014 — was there a transition to democracy. Why doesn’t people power work like it used to? He cites a couple of big factors in Democratic regression in comparative perspective: scope, methods, and causes, an article for Democratization, Diehl adds:

- One is that autocracies have figured out better strategies for blocking “color revolutions,” as Russian leader Vladimir Putin calls them. Among the innovations he and other dictators have adopted: closing down nongovernment groups; blocking pro-democracy funding from the United States and Europe; eliminating independent media, and, when a crisis comes, shutting down the Internet.

- Strongmen have also benefited from a strategic insight [aka authoritarian learning]: Faced with popular protests, they need not choose between surrender, like the Communists of Eastern Europe in 1989, and sending in tanks, as China did at Tiananmen Square. It’s enough simply to survive and persevere, using just enough repression to avoid a storming of the palace. Over time, a steady pressure of arrests and street repression, coupled with false promises of reform, can wear mass movements down. A lack of clear opposition leaders makes it easier.

If we break the period since 1976 into four equal segments of eleven years each, we find that the rate of democratic failure declined from 14 percent in the first period (1976–86) to under 11 percent in the next two segments, Diamond writes for the NED’s Journal of Democracy. In the most recent period (2009–19), however, this figure has increased to 18 percent, with democracy failing in key states including Bangladesh, Thailand, and Turkey, and for the first time in an EU member state, Hungary.

If we break the period since 1976 into four equal segments of eleven years each, we find that the rate of democratic failure declined from 14 percent in the first period (1976–86) to under 11 percent in the next two segments, Diamond writes for the NED’s Journal of Democracy. In the most recent period (2009–19), however, this figure has increased to 18 percent, with democracy failing in key states including Bangladesh, Thailand, and Turkey, and for the first time in an EU member state, Hungary.

The trend probably does not quite yet amount to what Samuel P. Huntington would have called a “reverse wave” of democratic breakdowns, but it is getting uncomfortably close, he observes.

Why doesn’t people power work like it used to? @washingtonpost‘s @JacksonDiehl asks. @LarryDiamond of @StanfordCDDRL & @NEDemocracy‘s @ThinkDemocracy & @JoDemocracy cites a couple of big factors https://t.co/TEFFUKTuLq

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 26, 2020