The Ukrainians are going to continue to rout the Russians. It’s hard to know exactly how long it’s going to take. But I think it’s going to happen sooner rather than later, Stanford University’s Francis Fukuyama tells The Post’s Greg Sargent:

It’s now possible to contemplate the eventual liberation of Crimea, given the rate at which the Ukrainians are going. That creates a whole different geopolitical outlook for everyone…. I do think that if Ukraine is able to defeat Russia, the demonstration effect is going to be really tremendous. It’s going to have domestic political consequences inside every democracy that’s threatened by one of these populist parties.

“The prospect that Ukraine can actually regain military momentum is entirely possible; indeed, it is likely in my view and unfolding as we speak,” Fukuyama predicted last week in the Journal of Democracy.

We must expect that a Ukrainian victory, and certainly a victory in Ukraine’s understanding of the term, also brings about the end of Putin’s regime, argues historian Anne Applebaum. To be clear: This is not a prediction; it’s a warning, she writes for The Atlantic:

We must expect that a Ukrainian victory, and certainly a victory in Ukraine’s understanding of the term, also brings about the end of Putin’s regime, argues historian Anne Applebaum. To be clear: This is not a prediction; it’s a warning, she writes for The Atlantic:

Many things about the current Russian political system are strange, and one of the strangest is the total absence of a mechanism for succession. Not only do we have no idea who would or could replace Putin; we have no idea who would or could choose that person. In the Soviet Union there was a Politburo, a group of people that could theoretically make such a decision, and very occasionally did. By contrast, there is no transition mechanism in Russia. There is no dauphin. Putin has refused even to allow Russians to contemplate an alternative to his seedy and corrupt brand of kleptocratic power.

First gradually, then suddenly

Rightist blogger Igor Girkin has observed that “The war in Ukraine will continue until the complete defeat of Russia. We have already lost, the rest is just a matter of time,” notes strategist Lawrence Freedman.

Rightist blogger Igor Girkin has observed that “The war in Ukraine will continue until the complete defeat of Russia. We have already lost, the rest is just a matter of time,” notes strategist Lawrence Freedman.

Because of the opacity of Putin’s decision-making and his delusional recent utterances, presenting Russia as the keeper of some core civilizational values, there is no suggestion that he has reached the point where he can acknowledge the position into which he has led his country, he writes. Prudence therefore requires us to assume that this war will not be over soon. But nor should it blind us to the possibility that events might move far faster than we assumed – first gradually, then suddenly.

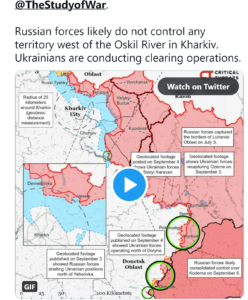

“The Ukrainian army has taken advantage of the relocation of the bulk of the Russian forces to the south and is trying to direct the course of the war, excelling in maneuver and showing great ingenuity,” said Mykola Sunhurovskyi, a military expert with the Kyiv-based think tank Razumkov Centre. Ukraine’s quick gains are “important both for seizing initiative and raising troops’ spirit,” he told The Associated Press.

Paradigm-shifting event

Russian nationalists are starting to openly criticize the war effort on national television, including Putin’s advisors and battlefield commanders. That’s an inch away from attacking the Russian autocrat directly, writes POLITICO’s Ryan Heath.

Ukrainian victory is not assured, Brian Whitmore writes for Foreign Policy. But if it happens, it would be a paradigm-shifting event for European security, on the scale of the events of 1989, when the countries of the old Warsaw Pact liberated themselves from Soviet domination. Officials in Washington and other Western capitals need to be prepared for the possibility.

W hether more “psychological blows” in Ukraine will significantly damage Putin’s standing is, of course, the big question of this conflict, adds analyst Cathy Young. Even before the Ukrainian offensive scored its stunning victories, two small-scale and doomed but nonetheless remarkable challenges to Putin were reported from within Russian political structures, she writes for The Bulwark:

hether more “psychological blows” in Ukraine will significantly damage Putin’s standing is, of course, the big question of this conflict, adds analyst Cathy Young. Even before the Ukrainian offensive scored its stunning victories, two small-scale and doomed but nonetheless remarkable challenges to Putin were reported from within Russian political structures, she writes for The Bulwark:

On September 7, a group of municipal representatives in the Smolny district of St. Petersburg sent an official letter to the Duma asking it to initiate treason charges against Putin and remove him from office. The letter noted that, as a result of the “special military operation” in Ukraine, “combat-ready divisions of the Russian army are being destroyed . . . and young, working-age citizens are being killed or left disabled”; “the Russian economy is suffering” because of sanctions and the brain drain; “the NATO bloc is expanding eastward”; and instead of demilitarizing, Ukraine was receiving new armaments.

Western support has been essential for Ukraine’s defensive fight against Russia and Ukrainians have proven capable in using modern Western-supplied equipment, like precision artillery and drones, to great effect, notes Rafael Loss, Coordinator for Pan-European Data Projects at the European Council for Foreign Relations. By taking the initiative and building a European coalition to support Ukraine with these systems Berlin would be at the centre of the effort to strengthen Europeans’ role and agency in standing up to Russian aggression.

“If something happens to him tomorrow, I believe that the system would survive; It’s still robust,” said political analyst Tatiana Stanovaya. “Conservative forces, siloviki [security officials] will seize the political initiative and take over. But if something happens to Putin later – one year or more – in this case, the risks of destabilisation are much higher. We will see infighting and the siloviki would have much less chance to keep the initiative. Next year the situation might be more different and difficult.”

Russia’s unprovoked and illegal invasion of a free and sovereign Ukraine is an extreme example of the increasingly bold and transgressive influence that autocratic governments seek to exert over democratic countries, but it is not the only one, says the National Democratic institute (NDI). Like Ukraine, other countries around the world find themselves under assault from foreign covert actors seeking to influence their elections, shift their public discourse and gain access to their economic and strategic resources.

Russia’s unprovoked and illegal invasion of a free and sovereign Ukraine is an extreme example of the increasingly bold and transgressive influence that autocratic governments seek to exert over democratic countries, but it is not the only one, says the National Democratic institute (NDI). Like Ukraine, other countries around the world find themselves under assault from foreign covert actors seeking to influence their elections, shift their public discourse and gain access to their economic and strategic resources.

To that end, on the occasion of International Democracy Day, NDI has partnered with the Open Government Partnership and Transparency International to develop and launch a new policy brief: “Openness and Oversight Measures to Counter Covert Foreign Political Finance.”

Security expert Mark Galeotti told Al Jazeera: “It’s honestly hard to see Putin going soon. For all the tales of illness, there’s no evidence he is seriously ill, and given how disastrously the war has gone, I can’t see him retiring unless he’s forced to go by the people around him. There are no obvious successors – it wouldn’t be [wise] to look as if you’re auditioning for a position that isn’t vacant.”

The fighting in Ukraine is the latest and worst of the wars fought over the remnants of the Soviet Union, an empire whose death throes continue some thirty years after the union itself ceased to exist. It will not, unfortunately, be the last, adds Johns Hopkins professor Hal Brands. Yet empires don’t die quickly: Their collapse, historian Serhii Plokhy wrote, is a “process rather than an event.”

The fighting in Ukraine is the latest and worst of the wars fought over the remnants of the Soviet Union, an empire whose death throes continue some thirty years after the union itself ceased to exist. It will not, unfortunately, be the last, adds Johns Hopkins professor Hal Brands. Yet empires don’t die quickly: Their collapse, historian Serhii Plokhy wrote, is a “process rather than an event.”

In their anger at high energy and food prices, European demonstrators from the far right and left are recycling the Kremlin’s narratives, one observer reports.

In its protracted standoff against Putin and the brutish neo-imperialism he represents, the West can only win if it stays united, Andreas Kluth writes for Bloomberg. This is why Putin will do his utmost to keep spreading lies and disinformation in the West, in the hope of building a “fifth column” that fights for him from behind enemy lines. Western leaders — and not only those holding political office — must do everything they can to call out those lies and counter them with truth. The biggest test yet will come during this hot autumn.

In their anger at high energy and food prices, European demonstrators from the far right and left are recycling the Kremlin’s narratives, Bloomberg’s @andreaskluth writes.https://t.co/t7cvo4dbEA

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) September 12, 2022

If there is one lesson to be learned after six months of war in Ukraine, it is the danger represented by authoritarian regimes in the triggering and management of conflicts, adds French analyst Dominique Moïsi. Power is complete isolation. In war time, authoritarian regimes are at once more dangerous and more fragile than others because they know that for them, losing war means losing power — or losing their life.

Putin wanted the “Finlandization” of Ukraine. Instead, he got the “NATO-ization” of Finland and Sweden, he writes for WorldCrunch. One lesson stands out with even more clarity: there are limits to military power, mostly when the quantity of troops and weapons are not enough to differentiate the quality and determination of men.

We must expect that a Ukrainian victory, and certainly a victory in Ukraine’s understanding of the term, also brings about the end of Putin’s regime, @NEDemocracy board member @anneapplebaum writes for @TheAtlantic #UkraineRussianWar https://t.co/mK9I1JULse

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) September 12, 2022