Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy attracted global attention when he rejected a U.S. offer to evacuate, replying defiantly, “The fight is here. I need ammunition, not a ride.”

That response “will go down in history,” says Kenneth Dekleva, a senior fellow at the George H. W. Bush Foundation for U.S.-China Relations. “After two years of a worldwide pandemic where we’ve seen so many failures of leadership, both in authoritarian societies and in democratic societies in the West, Zelenskyy is a breath of fresh air. … Zelenskyy has inspired people, and he’s shown us that good leadership and courage, heroism — these kinds of core values — matter,” he tells VOA’s Dora Mekouar.

Zelenskyy demonstrates that democratic leadership has the capacity to be morally justified while also rousing people’s emotions, she writes.

“The fact that Zelenskyy appeals not just to the head, but to the heart, has been extremely promising, because it indicates that democracy might have rhetorical power as well as intellectual power,” says Michael Blake, a professor of philosophy, public policy and governance at the University of Washington.

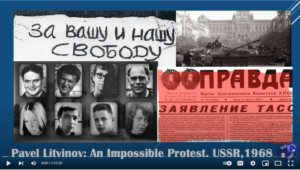

What’s happening in Ukraine today is a harbinger of liberal democracy’s revival, says Pavel Litvinov—a Soviet dissident exiled to Siberia for participating in the famous 1968 Red Square demonstration (see below).

What’s happening in Ukraine today is a harbinger of liberal democracy’s revival, says Pavel Litvinov—a Soviet dissident exiled to Siberia for participating in the famous 1968 Red Square demonstration (see below).

“I never believed democracy would perish,” he tells The Bulwark’s Cathy Young. “It can be lost in certain places, for a certain amount of time. But who would have thought that Ukraine would make a 180-degree turn while Russia remained stuck in the Soviet Union?”

In the wake of the Ukraine invasion, democratic nations must understand democracy as a matter of world security, not simply a values proposition, argues Laura Thornton, director and senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for Securing Democracy. Autocrats weaponize such crises to undermine public belief in institutions, governance and democratic processes so how democracies respond both internally and globally matters, she writes for Lawfare:

- First, democratic nations must get their own houses in order. According to international democracy assessments, old as well as new democracies are under threat. …

-

ZMINA

Second, a coordinated global democracy network is needed. This could be done through the Summit for Democracy framework…. or other existing global institutions and initiatives. Or perhaps through the establishment of a new commission of democracies, including civil society actors, to provide collective security and early warning systems….

- Third, democracy assistance should go after the authoritarian playbook. Democracies must support donor-recipient countries, and each other, to deter and build defenses against mal/mis/disinformation, going beyond a defensive whack-a-mole approach to preemptively recognizing and pre-bunking information operations. ….

Fourth, democracy investments, both at home and abroad, should focus on the demand side—building resilient communities and publics. …. Research on resilience has shown that communities with a strong sense of civic life and social cohesiveness are more durable….

Fourth, democracy investments, both at home and abroad, should focus on the demand side—building resilient communities and publics. …. Research on resilience has shown that communities with a strong sense of civic life and social cohesiveness are more durable….- Finally, donor countries and democracy assistance organizations must enhance support to democrats in closed societies.

Putin can’t take Ukraine so he’s taking its people, says Ukrainian NGO ZMINA. Dozens of civilians are missing and thousands more deported to Russia. These people have names and faces. Please share them and demand their safe return. Ask @KremlinRussia_E ‘Where are the taken?’ #TheTaken

The U.S. Senate Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe held a hearing (above) on opposing Russian imperialism in Ukraine and beyond, with testimony from Gen. Phillip Breedlove (ret.), senior fellow at the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Center for European and Transatlantic Studies; Michael Kimmage, fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States; and Miriam Lanskoy, senior director for Russia and Eurasia at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Ukraine doesn’t just deserve EU membership, its bid could revive and rejuvenate Europe. From @OxanaShevel & @PopovaProf’s newest piece on our site: https://t.co/hKoP5hGfs0. @McFaul @anneapplebaum @peterpomeranzev @RTPerson3

— Journal of Democracy (@JoDemocracy) March 28, 2022

“For many Ukrainians, this is almost an existential threat in that they see losing meaning an end to Ukrainian democracy and, particularly for younger people, meaning an end to the vision of Ukraine’s future as a normal European state,” former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine Steven Pifer, told a Brookings forum.