If one imagines a future in which Russia enjoys democracy and lasting peace, writes Masha Gessen, then [Novaya Gazeta editor-in-chief Dmitry] Muratov, who has maintained a fragile sort of peace for a community that exercises freedom of expression in a profoundly unfree country, embodies the precondition for such a future.

By all accounts, the paper’s continued existence is the result of Muratov’s unceasing negotiations with the many men in and near the Kremlin who have the power—and, often, the desire—to shut Novaya Gazeta down, To keep his colleagues safe, Muratov has struck many fraught bargains, she writes for The New Yorker:

In 2009, after one of Novaya Gazeta’s correspondents in Chechnya, Natalya Estemirova, was kidnapped and killed, Muratov learned that a second reporter who wrote about Chechnya was in imminent danger. Through a government official, he made an offer: in exchange for the second reporter’s safety, Novaya Gazeta would refrain from covering Chechnya for a year. “Maybe that was the wrong thing to do,” Muratov said in an interview for a film released by Novaya Gazeta for the fifteenth anniversary of [Anna] Politkovskaya’s death. “But I’d do it all over again.”

Can Russia’s Press Ever Be Free? https://t.co/Kd8vDyrSSE via @NewYorker

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) November 16, 2021

Soviet dissident and physicist Andrei Sakharov used to argue that repression at home invariably becomes instability abroad, The Economist (above) observes. His own life was evidence of it. Today Sakharov’s thesis is being demonstrated once again—in reverse. According to Memorial, a human-rights group, Russia has more than twice as many political prisoners than at the end of the Soviet era.

Russian prosecutors have now demanded that Memorial, which Sakharov helped set up to document Soviet abuses, will be shut down.

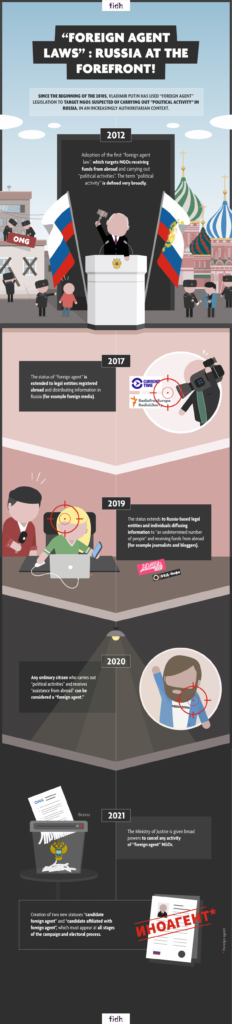

Memorial has two key entities: Memorial Human Rights Center and International Memorial Society, adds FIDH, the International Federation of Human Rights. On November 11, International Memorial Society received a letter from Russia’s Supreme Court informing them that on November 8 the Prosecutor General’s Office had filed a lawsuit seeking their liquidation over repeated violations of Russia’s “foreign agents” legislation. The court hearing is set for November 25.

Memorial has two key entities: Memorial Human Rights Center and International Memorial Society, adds FIDH, the International Federation of Human Rights. On November 11, International Memorial Society received a letter from Russia’s Supreme Court informing them that on November 8 the Prosecutor General’s Office had filed a lawsuit seeking their liquidation over repeated violations of Russia’s “foreign agents” legislation. The court hearing is set for November 25.

More than 60 Russian scholars, including members of the Academy of Sciences and the Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, said the announcement “is an attempt to deprive the nation of its memory,” RFE/RL reports. Nearly 23,000 signed an online petition called “Hands Off Memorial!” in the four days since the announcement.

Two weeks after he received the Nobel Peace Prize, Novaya Gazeta’s Muratov participated in the Valdai meeting, Putin’s annual gathering of handpicked journalists and scholars, The New Yorker’s Gessens adds. Muratov made no mention of using the Nobel money to help media organizations that had been declared foreign agents, as he had previously promised. He had not dropped the plan—he will channel the money through the Politkovskaya prize. But this was neither the time nor the place to draw attention to his scheme. RTWT

European Union foreign ministers agreed to impose sanctions on Russian mercenary company Wagner Group, as European diplomats warned that the company poses a growing threat to EU interests, the Wall Street Journal reports. The EU is acting amid renewed turbulence in European-Russian relations over a Russian military buildup on Ukraine borders, the Kremlin’s support for Belarus strongman Alexander Lukashenko, uncertainty over Russian gas supplies and Moscow’s crackdown on the country’s domestic opposition.

European Union foreign ministers agreed to impose sanctions on Russian mercenary company Wagner Group, as European diplomats warned that the company poses a growing threat to EU interests, the Wall Street Journal reports. The EU is acting amid renewed turbulence in European-Russian relations over a Russian military buildup on Ukraine borders, the Kremlin’s support for Belarus strongman Alexander Lukashenko, uncertainty over Russian gas supplies and Moscow’s crackdown on the country’s domestic opposition.

Western governments have no effective strategy other than sanctions to combat the mixture of destabilization, disinformation, organized crime and military posturing coming from Minsk and Moscow, argues Paul Mason, the author of PostCapitalism. But strong, multilateral action – involving sanctions of a kind that would cripple the Russian and Belarusian financial systems – might be the only way of dissuading Putin and Lukashenko from further adventurism, he writes for The New Statesman.

Democracies can respond to Russia’s belligerence by building social cohesion and ensuring democracy works, including by increasing resilience to malicious propaganda and projecting

coherent messages, says a prominent analyst.

The understanding still needs to be promoted that with Russia’s political doctrine profoundly at odds with the interests of Western democracies, the current disagreement is not about Crimea,

Ukraine or Syria; it is about a fundamental incompatibility of world views, and the dangerous implications of this clash for governments, societies and people, notes Chatham House Russia expert Keir Giles. Put simply, where the desire to avoid open conflict may be a substantial motivating factor for Western liberal democracies, it plays a demonstrably different role in Russian decision-making:

Russia can send out broadly coordinated information through a loosely integrated system that extends from President Putin down through the bottom-feeder echelons of online troll armies. For Western nations, by contrast, signaling is complicated by democracy – both within a single nation and in alliances. Democracies, by their very nature, may find it hard to stick to their own policies and declared boundaries, through political change and being subject to the pressure of domestic public opinion.

There are two persistent assumptions in Western policy towards Russia to which policymakers repeatedly return, but which repeatedly founder, Giles adds:

- to assume that Russia has an interest in cooperation with the West or in reducing tensions that could lead to conflict;

- to assume that there is anything the West can do to affect Moscow’s deeply held conviction that the West harbors hostile intent towards it.

But for Western countries, clarity of messaging, coupled with a degree of honesty and transparency, is also essential with regard to their own populations, Giles contends. It is impossible for any democracy to defend itself effectively against threats of which the bulk of its population remains unaware.