Doubts about Latin America’s democracies’ capacity to operate fairly and effectively likely explain lukewarm public support for and satisfaction with democracy, write Noam Lupu and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister of Vanderbilt University’s Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP).

Doubts about Latin America’s democracies’ capacity to operate fairly and effectively likely explain lukewarm public support for and satisfaction with democracy, write Noam Lupu and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister of Vanderbilt University’s Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP).

The LAPOP Lab at Vanderbilt University releases today its 2021 Pulse of Democracy report on the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC). The 2021 assessment yields a mixed report. The COVID-19 pandemic that began in March 2020 presented institutions with a severe and prolonged stress test. Research generated by LAPOP Lab in the first year of the pandemic revealed its potential to buoy support for the executive office without contributing to a further decline in support for democracy.[1] Data from the 2021 AmericasBarometer affirm this tendency: support for democracy remained steady in the LAC region, while tolerance for centralizing power in the executive increased.

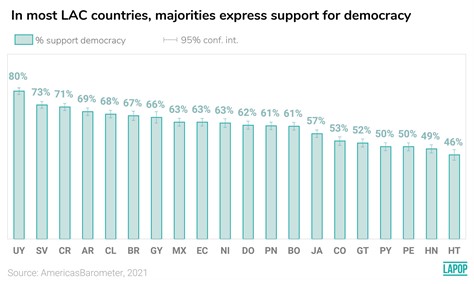

The pandemic increased the public’s need for government services while simultaneously stretching and diminishing the state’s capacity to provide them. The fact that support for democracy remained stable in the midst of this crisis is an impressive sign of resilience (see figure 1). In fact, satisfaction with democracy increased marginally in 2021 – a sign that the public does not blame democracy for its collective suffering.

Question wording: Democracy may have problems, but it is better than any other form of government. To what extent do you agree or disagree with this statement? The response scale ranges from one to seven and we code answers values from five to seven as support for democracy.

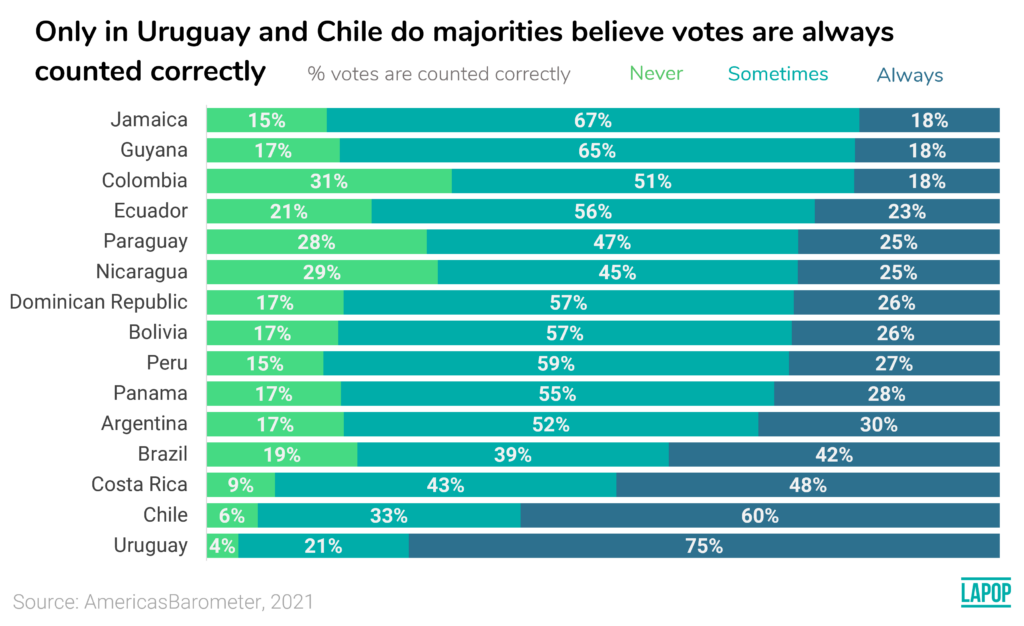

Yet, skepticism regarding electoral democracy persists. Large numbers of citizens disagree that democracy is the best available political system. What does the public want instead? One answer provided by the 2021 AmericasBarometer is voice. When asked to choose between freedom of speech or guaranteed access to basic income and services, the vast majority of LAC residents opt for freedom of speech. In contrast, when asked to choose between a guaranteed basic standard of living or elections, fewer than half choose the latter. This disregard for elections – a key mechanism by which electoral democracies translate the people’s voice into politics – is grounded in views that elections, and elected representatives, are flawed and untrustworthy (see figure 2).

Question wording: I will mention some things that can happen during elections and ask you to indicate if they happen in [country]…Votes are counted correctly and fairly. Would you say it happens always, sometimes or never?

These attitudes reveal a critical challenge to the health of democracy in the region: to the degree that citizens feel their voices are not being heard through elections, they may accept deviations from democratic practices. El Salvador is an exemplar of this problem. The 2021 AmericasBarometer survey reveals that a large majority of the public has closed ranks behind President Nayib Bukele, who has maintained public support despite ordering security forces to physically intimidate the legislature and centralizing power within the executive office. El Salvador’s Freedom House ranking has decreased under Bukele. However, the public’s enthusiasm for his style of politics has bolstered support for and satisfaction with democracy and what it is delivering.

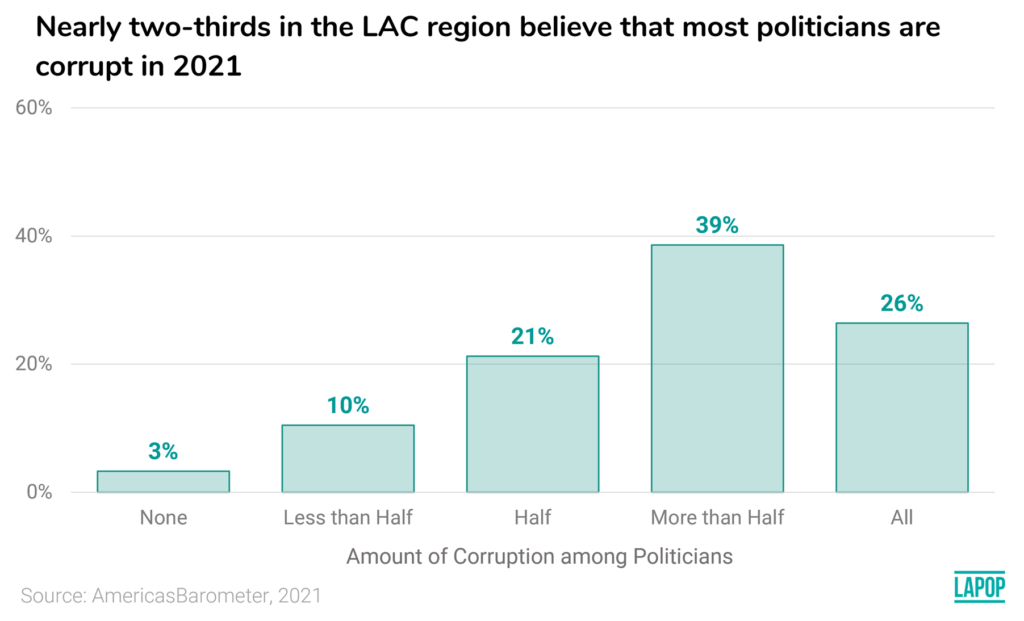

What would it take to increase confidence in electoral democracy? The AmericasBarometer provides an answer: clean governance. More than three in five citizens in the average LAC country believe that corruption is widespread among elected officials (see figure 3) – a rate that has held fairly steady since the question was introduced in 2016. These perceptions are kept aloft by recurring high-level scandals, most recently involving vaccine access and offshore financial accounts. Meanwhile, corruption victimization experiences in dealings with public officials have increased across the region – possibly the result of people’s increased contact with public officials during the pandemic, or because bureaucrats themselves faced greater financial insecurity.

Question wording: Thinking of politicians in [country], how many do you believe are involved in corruption? (1) None (2) Less than half of them (3) Half of them (4) More than half of them (5) All

The public’s commitment to democracy in the LAC region remains fragile. A positive result in this year’s AmericasBarometer survey is resilience in support for democracy in the abstract and marginal gains in satisfaction with democracy – despite recession conditions and the tremendous strain the pandemic placed on public service delivery. The public strongly asserts its desire to have a voice in politics. Yet, people are skeptical of electoral democracy’s capacity to deliver. Many distrust elections and elected representatives. Doubts regarding democracy’s capacity to operate fairly and effectively likely account for why average levels of support for and satisfaction with democracy remain comparatively lower than they were a decade ago. For the pulse of democracy to gain strength, citizens in the LAC region will need to see good performance and clean politics from their governments. Read the full report here.

Dr. Noam Lupu is Associate Professor of Political Science at Vanderbilt University and Associate Director of LAPOP Lab. Dr. Elizabeth J. Zechmeister is Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Political Science at Vanderbilt University and Director of LAPOP Lab.

[1] Lupu, Noam, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister. 2021. “The early COVID-19 pandemic and democratic attitudes.” PLOS ONE 16(6): e0253485. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253485

What is specific about Latin America’s democratic regression relative to the global malaise evident in other regions? the National Endowment for Democracy’s Senior Director Miriam Kornblith asked in today’s Woodrow Wilson Center virtual discussion on the AmericasBarometer Study. The salience of concerns about crime and personal insecurity are distinctive to the region, which hosts five of the world’s most violent democracies, said LAPOP’s Noam Lupu.

What is specific about Latin America’s democratic regression relative to the global malaise evident in other regions? the National Endowment for Democracy’s Senior Director Miriam Kornblith asked in today’s Woodrow Wilson Center virtual discussion on the AmericasBarometer Study. The salience of concerns about crime and personal insecurity are distinctive to the region, which hosts five of the world’s most violent democracies, said LAPOP’s Noam Lupu.

The Wilson Center’s Latin American Program and LAPOP hosted a virtual discussion on “The Pulse of Democracy in the Americas: Results from the 2021 AmericasBarometer Study.” Speakers: Peter Natiello, acting assistant administrator, USAID’s Latin America and Caribbean Bureau; Adriana Camacho, senior economist and consultant with the United Nations Development Programme; Elizabeth Zechmeister, professor of political science at Vanderbilt University and director of LAPOP; and Noam Lupu, associate professor of political science at Vanderbilt University and associate director of LAPOP. Watch the event LIVE with this Zoom Webinar link. Full details here.