Beijing agents pressured two Chinese-Australian authors to provide information about a secret Canberra inquiry into Chinese meddling in domestic politics, local media reported Monday:

Beijing agents pressured two Chinese-Australian authors to provide information about a secret Canberra inquiry into Chinese meddling in domestic politics, local media reported Monday:

Yang Jun, a novelist and democracy advocate, and Feng Chongyi, a Sydney-based university professor and former newspaper publisher, were reportedly interrogated over the classified probe. The pair are both friends of John Garnaut, a former journalist who was heading up the inquiry…..

A joint investigation published Monday by The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and national broadcaster ABC found China had waged an intelligence operation to gain details of the probe ordered in 2016 by then-Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, AFP reports.

“There are several authoritarian states who are involved in foreign influence across the globe. But in Australia the Chinese Communist Party is probably the most active,” said Andrew Hastie, who chairs Canberra’s intelligence and security committee. “China is seeking to influence our elites, particularly our political and business elites, in order to achieve their strategic objectives.”

Chinese Communist Party-aligned billionaire Huang Xiangmo paid tens of thousands of dollars to a former Liberal minister to secure a one-on-one meeting with Peter Dutton as Mr Huang mounted a back-room campaign to win Australian citizenship, according to reports.

Chinese Communist Party-aligned billionaire Huang Xiangmo paid tens of thousands of dollars to a former Liberal minister to secure a one-on-one meeting with Peter Dutton as Mr Huang mounted a back-room campaign to win Australian citizenship, according to reports.

Concern is growing about Beijing’s influence ahead of Australia’s forthcoming elections, the Times adds:

In 2017, a prominent Australian senator, Sam Dastyari, resigned over accusations of lobbying for Beijing and taking money from Chinese-born political donors. The government passed a foreign interference law, requiring lobbyists for other countries to register and disclose their activities — one of many efforts to push the Chinese government’s soft-power campaign out of the shadows.

In the run-up to a Beijing-EU summit Tuesday, China’s top representative to the European Union, Zhang Ming, has lamented Europe’s toughening stance toward Beijing, pushing back against the term “systemic rival” adopted by European countries to describe China, arguing that such polarizing language was not even used during the Cold War at a time of icy relations, POLITICO reports.

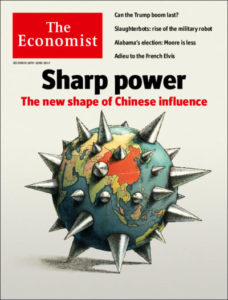

uropean observers express concern about the role that China’s Confucius Institutes – considered by some to be the “tip of the iceberg” of Beijing’s sharp power – have played in spying and in suppressing any attempt to defend human rights.

uropean observers express concern about the role that China’s Confucius Institutes – considered by some to be the “tip of the iceberg” of Beijing’s sharp power – have played in spying and in suppressing any attempt to defend human rights.

Meanwhile, the FBI is examining whether a Chinese woman, Yujing Zhang, arrested at President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Florida resort last month, carrying “malicious malware has any links to Chinese intelligence or political influence operations, two U.S. government sources told Reuters.

But Beijing’s sharp power may have encountered a snag in the Indian Ocean.

A political party led by the president of the Maldives appeared to have won decisively in parliamentary elections over the weekend, a result that may help him restore political freedoms in a strategically important country with an authoritarian past, the New York Times reports:

The president, Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, had won a resounding victory in presidential elections last September. But parts of his party’s agenda have been stymied because some of its allies in a governing coalition are aligned with a former strongman leader, Abdulla Yameen, who has been widely accused of corruption and repression.

Some political analysts saw the victory last year for Mr. Solih, who has been skeptical of China’s influence, as good news for India’s interests. …Still, Constantino Xavier, a foreign policy fellow at Brookings India in New Delhi, said the “lure of cheap and easy money” made it likely that the Maldives’s relationship with China would deepen, “despite everything that leaders will say in public.”

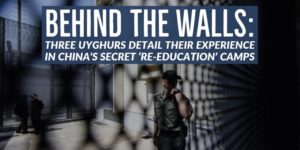

The recent mass arrests of scores of leading academics and intellectuals in western China is one of many indications that the Chinese regime’s current campaign against the native Uighur, Kazakh and other peoples is already a genocide, argues Magnus Fiskesjö, an associate professor of anthropology at Cornell University.

The recent mass arrests of scores of leading academics and intellectuals in western China is one of many indications that the Chinese regime’s current campaign against the native Uighur, Kazakh and other peoples is already a genocide, argues Magnus Fiskesjö, an associate professor of anthropology at Cornell University.

The Uighur Human Rights Project recently counted 386 targeted academics, artists and other prominent intellectuals as having been arrested by the regime, he writes for Inside Higher Education:

Change.org

China can no longer be regarded as an authoritarian country that is perhaps moving in the right direction. No, we are witnessing a monstrous mass assault on human dignity. It is an intentional, well-planned, multipronged genocide, targeting the dignity of whole peoples and cultures by humiliating their best and brightest, including our fellow scholars.

“If you look deeply at Xi’s calls for China to lead reform of the global system, what they are saying is terrifying,” argues Michael Hart, a China expert at the Center for American Progress. “They want to make the world system more authoritarian so that China can integrate without facing political concerns,” he tells the Nation.

Despite its considerable investments, China still suffers a soft-power deficit, notes Harvard University’s Joseph S. Nye, Jr., author of Is the American Century Over? and the forthcoming Do Morals Matter? Presidents and Foreign Policy from FDR to Trump.

Xi has proclaimed a “Chinese Dream” of a return to global greatness. As economic growth slows and social problems increase, the Party’s legitimacy will increasingly rest on such nationalist appeals, he writes for Project Syndicate:

Xi has proclaimed a “Chinese Dream” of a return to global greatness. As economic growth slows and social problems increase, the Party’s legitimacy will increasingly rest on such nationalist appeals, he writes for Project Syndicate:

Over the past decade, China has spent billions of dollars to increase its attractiveness to other countries, but international public opinion polls show that China has not gained a good return on its investment. Repressing troublesome ethnic minorities, jailing human-rights lawyers, creating a surveillance state, and alienating creative members of civil society such as the renowned artist Ai Weiwei undercut China’s attraction in Europe, Australia, and the US.

A Canadian couple who pulled their daughter out of the controversial Confucius Institute in their neighbourhood school have discovered new details about the program, CBC reports:

Bronwyn Bonney and Parker Coates say they were alarmed last year that they weren’t told their daughter was in the program, which is funded by the Chinese government and uses teachers from China.

“We’re talking about a nation that right now has hundreds of thousands of people in internment camps for having the wrong kind of Chinese culture,” Coates said. “Chinese citizens who are Muslim or Falun Gong are being incarcerated, and we’re welcoming this in to teach our children about Chinese culture. That just seems totally out of whack.”

“We’re talking about a nation that right now has hundreds of thousands of people in internment camps for having the wrong kind of Chinese culture,” Coates said. “Chinese citizens who are Muslim or Falun Gong are being incarcerated, and we’re welcoming this in to teach our children about Chinese culture. That just seems totally out of whack.”

“This program is inherently propaganda,” Bonney said in an interview. “It’s propaganda in that it’s an effort to brainwash and influence people’s ideas of a certain place.

“There is no boundary between politics and what passes for culture in contemporary China. The Cultural Revolution … was not called a ‘cultural’ revolution for nothing,” wrote Emeritus Professor John Fitzgerald from the Swinburne University of Technology’s Centre for Social Impact. “The Cultural Revolution may be over, but the politics of controlling what can be said in the media and taught in universities has returned with a vengeance.”

China’s successful efforts to conceal its problems cannot make them go away, adds Harvard’s Nye. In addition to the soft power deficit, at least four major long-term problems confront China:

- First, there is the country’s unfavorable demographic profile. China’s labor force peaked in 2015, and it has passed the point of easy gains from urbanization. The population is aging, and China will face major rising health costs for which it is poorly prepared. This will impose a significant burden on the economy and exacerbate growing inequality.

Second, China needs to change its economic model. …[but] China’s intellectual property policies and rule-of-law deficiencies are discouraging foreign investment and costing it the international political support such investment often brings. And China’s high rates of government investment and subsidies to SOEs disguise inefficiency in the allocation of capital.

Second, China needs to change its economic model. …[but] China’s intellectual property policies and rule-of-law deficiencies are discouraging foreign investment and costing it the international political support such investment often brings. And China’s high rates of government investment and subsidies to SOEs disguise inefficiency in the allocation of capital.- Third, while China for more than three decades picked the low-hanging fruit of relatively easy reforms, the changes it needs now are much more difficult to introduce: an independent judiciary, rationalization of SOEs, and liberalization or elimination of the hukou system of residential registration, which limits mobility and fuels inequality. Moreover, Deng’s political reforms to separate the party and the state have been reversed by Xi.

- That brings us to the fourth problem. Ironically, China has become a victim of its success…Deep structural reforms that can move China away from reliance on high levels of government investment and SOEs are opposed by Party elites who derive tremendous wealth from the existing system. Xi’s anti-corruption campaign can’t overcome this resistance; instead, it is merely discouraging initiative.