Defending core values should be an essential national interest for any foreign policy responding to challenges by revisionist powers, argues a recent analysis. But does an ethical dimension to foreign policy and a firm commitment to core democratic values serve as a countervailing force to authoritarian powers or is a “realist”, hard-power approach likely to be more effective against malign actors?

Defending core values should be an essential national interest for any foreign policy responding to challenges by revisionist powers, argues a recent analysis. But does an ethical dimension to foreign policy and a firm commitment to core democratic values serve as a countervailing force to authoritarian powers or is a “realist”, hard-power approach likely to be more effective against malign actors?

A democratic values-based foreign policy strategy is rooted in faith in democratic self-government, not just as being better than all the alternatives, a recent report contends.

Many agree that in order to compete with Beijing, the United States should work with allies that share its values to develop a common strategy for reaching mutual goals that have fostered seven decades of shared prosperity. Isolationism, nativism, and protectionism won’t work, says U.S. Senator Chris Coons. U.S. foreign policy is stronger when it enjoys bipartisan support, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

For the United States to play a steady, stabilizing role in world affairs, its allies and adversaries must know that its government speaks with one voice and that its policies won’t shift dramatically with changing domestic political winds. The best way to ensure that clarity and consistency is to pursue policies that are guided by American values of freedom, openness, opportunity, and inclusivity—and that have the support of policymakers and ordinary Americans across the political spectrum.

The best way to ensure that clarity & consistency is to pursue policies guided by values of freedom, openness, opportunity, and inclusivity—that have support across the political spectrum, argues @ChrisCoons https://t.co/AkSSwflY3S via @ForeignAffairs

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 7, 2020

The authoritarian resurgence has made values and rights into a new terrain of strategic competition, according to a leading democracy advocate. The good news for democratic forces is that despite autocrats’ increasingly aggressive information warfare, global struggles from Hong Kong to Belarus affirm the robust demand for democratic rights, inclusion and freedom, said Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy, addressing a webinar on A Battle of Narratives: Building Public Support for Democratic Renewal.

But values-promotion is no longer a one-way street, observers suggest.

But values-promotion is no longer a one-way street, observers suggest.

Washington must now not only fortify its own values around the world, but also fend off a competing set of prescriptions that were made in Beijing but are increasingly being felt in Boston, PEN’s Suzanne Nossel writes for Foreign Policy. The Chinese government is working its will through a widening network of governments, technologies, universities, and corporations that are willing to compromise on Western values to assure access to Chinese money and markets.

In the coming decades, however, rapid population aging and the rise of automation will dampen faith in democratic capitalism and fracture the so-called free world at its core, argues Michael Beckley, Associate Professor of Political Science at Tufts University, Jeane Kirkpatrick Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and the author of Unrivaled: Why America Will Remain the World’s Sole Superpower:

To keep the current liberal order together, the United States would need to take an unusually generous view of its interests. It would need to subordinate the pursuit of national wealth and power to a common aspiration for international order. It would also need to redistribute wealth domestically to maintain political support for liberal leadership abroad.

As the world enters a period of demographic and technological disruption, however, such a path will become increasingly hard to follow. As a result, there may be little hope that the United States will protect partners, patrol sea-lanes, or promote democracy and free trade while asking for little in exchange.

As the world enters a period of demographic and technological disruption, however, such a path will become increasingly hard to follow. As a result, there may be little hope that the United States will protect partners, patrol sea-lanes, or promote democracy and free trade while asking for little in exchange.

Americans are unenthusiastic about promoting democracy overseas but willing to partner with allies to defend U.S. institutions from foreign meddling. Thus, the United States could forge a coalition of democracies to coordinate collective sanctions against foreign powers that interfere in democratic elections. Eventually, the coalition could become a liberal bloc that excludes countries that do not respect open commerce and freedom of expression and navigation, he writes for Foreign Affairs.

But could the liberal order be revived today? asks CFR expert Stewart Patrick. G. John Ikenberry’s new book suggests that liberal internationalism might yet rise from the ashes, but that any such renaissance depends on resolving six tensions within the system itself, he writes for World Politics Review:

- First, liberal internationalists must forge a new global economic bargain that tempers concerns about market “efficiency” with the imperatives of “social stability.”

- Second, they need to recalibrate the “legal bases for intervention,” so that any such action is consistent with the principle of sovereignty as responsibility.

- Third, they must decide between pursuing a universalist conception of international order and adopting a “club-like” approach focused, as in the Cold War, on established liberal democracies.

- Fourth, they need to figure out how to deal with illiberal powers like China and Russia, choosing among the strategies of accommodation, confrontation and selective engagement.

- Fifth, liberal internationalists must recalibrate the balance between hegemony and restraint in U.S. global engagement. The goal should be to foster a shared conception of international leadership among Western nations, appropriate to America’s (relative) decline.

- Finally, liberal internationalists everywhere need to temper their Whiggish expectations that the march of progress is steady and inexorable. The arc of history may ultimately bend in their direction, but they are apt to encounter many switchbacks along the way.

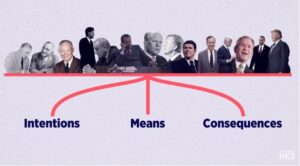

Effective moral reasoning in foreign policy should be three-dimensional, ‘weighing and balancing the intentions, the means, and the consequences of presidents’ decisions’, Joseph Nye asserts in Do Morals Matter? Presidents and Foreign Policy from FDR to Trump. But the US must also confront two global shifts:

Effective moral reasoning in foreign policy should be three-dimensional, ‘weighing and balancing the intentions, the means, and the consequences of presidents’ decisions’, Joseph Nye asserts in Do Morals Matter? Presidents and Foreign Policy from FDR to Trump. But the US must also confront two global shifts:

- The first is Asia’s – especially China’s – growing economic and political power.

- The second stems from rapidly changing technology, which empowers non-state actors and crowds ‘the stage on which governments act, creating new instruments, problems, and potential coalitions’.

These challenges do not require an entirely new approach, but rather one that prioritizes the values that animated US foreign policy after the Second World War, adds Daniel Strieff, author of ‘Jimmy Carter and the Middle East: The Politics of Presidential Diplomacy.’ Recently, America has weakened its international standing by shredding alliances, instituting protective economic policies and pursuing fruitless and unpopular wars. But power flounders without legitimacy, he writes in a review for Chatham House.

“International order has depended on the ability of a leading state to combine power and legitimacy,” Nye writes. “Morals matter, when seen in all three dimensions, because they are part of the secret of a successful international order.”

3-pillar freedom agenda

Credit ESI

UK Foreign Secretary Dominc Raab this week promoted a “three-pillar freedom agenda” for the UK’s foreign policy: defending media freedoms, the freedom of religion & belief, and imposing Magnitsky sanctions on those who constrain freedoms, notes British Foreign Policy Group analyst Sophia Gaston.

Like Moliere’s women characters who spoke prose without realising it, foreign policy practitioners invariably if unwittingly employ ethical criteria in decision-making, argues the NED’s Michael Allen. Yet recent analyses and debates on both sides of the Atlantic suggest a profound crisis of confidence in the resilience of democratic institutions and the liberal values on which they rest.

On the other hand, by puncturing the comfortable orthodoxies of the post-Cold War era, the current democratic recession and the COVID-19 pandemic may provide an opportunity for a reappraisal, revival and reassertion of liberal democratic ideas and institutions, he wrote for the London-based Foreign Policy Centre:

The UK needs “a thorough re-appraisal of the dominant assumptions that have guided our strategic thinking,” former Defence and Foreign Secretary Sir Malcolm Rifkind wrote in the preface to a recent report. ……. A leading US strategist echoes the demand of a “new set of assumptions” to underpin foreign policy. “Contrary to the optimistic predictions made in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, widespread political liberalisation and the growth of transnational organisations have not tempered rivalries among countries,” former National Security official Nadia Schadlow wrote for Foreign Affairs. Likewise, “the uncomfortable truth,” is that “visions of benevolent globalization and peace-building liberal internationalism have failed to materialise, leaving in their place a world that is increasingly hostile to American values and interests.”

Finding Britain’s role in a changing world: Defining the values the UK should stand for and protecting its ability to defend them. The Foreign Policy Centre webinar – Wednesday 4th November, 4pm-5pm BST (UK time)

Speakers:

- Tom Tugendhat MP, Chair of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee

- Dr Kate Ferguson, Co-Director of Protection Approaches

- Benjamin Ward, UK Director of Human Rights Watch

Chair: Deborah Haynes, Foreign Affairs Editor of Sky News

This public zoom event is part of the Foreign Policy Centre’s ongoing Finding Britain’s role in a changing world project responding to the UK’s Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy. It will comprise a short keynote speech from Tom Tugendhat MP, Chair of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee, expert responses and an audience Q&A session.

The event will take stock of the deliberations around the Government’s Integrated Review, with an emphasis on issues raised by the FPC’s project so far through its ‘Finding Britain’s Role in a changing world’ publications: ‘The Principles of Global Britain’ and ‘Protecting the UK’s ability to defend its values’. The discussion will address the state of political situations around the world that the UK foreign and security policy will need to respond to (with a focus on rising authoritarianism and pressures on liberal democracy and multilateral institutions). It will examine how to define and decide on the principles and values that should underpin UK Foreign Policy, including how to involve the British public in the process of deciding on them. It will also discuss how those values should be best incorporated into the policy making process. The event will then explore how the UK’s existing successes in the promotion of its values can be protected and built on, deliberate how to best ensure the merged FCDO is made a success, and examine the importance of protecting the UK’s soft power.

The event will take stock of the deliberations around the Government’s Integrated Review, with an emphasis on issues raised by the FPC’s project so far through its ‘Finding Britain’s Role in a changing world’ publications: ‘The Principles of Global Britain’ and ‘Protecting the UK’s ability to defend its values’. The discussion will address the state of political situations around the world that the UK foreign and security policy will need to respond to (with a focus on rising authoritarianism and pressures on liberal democracy and multilateral institutions). It will examine how to define and decide on the principles and values that should underpin UK Foreign Policy, including how to involve the British public in the process of deciding on them. It will also discuss how those values should be best incorporated into the policy making process. The event will then explore how the UK’s existing successes in the promotion of its values can be protected and built on, deliberate how to best ensure the merged FCDO is made a success, and examine the importance of protecting the UK’s soft power.

Please RSVP via Eventbrite here or below. Zoom login details will be sent to registered attendees prior to the event.