Eurasia Group

Powerful global forces are eroding the foundations of the liberal order and empowering illiberal figures like Britain’s pinstriped populist Nigel Farage, The Economist observes:

- The most powerful of these global forces is, somewhat paradoxically, nationalism. The past decade has seen a revolt against the world-is-flat globalism that was all the rage at the turn of the century, a revolt that has swept overtly nationalist governments to power in America, Brazil, Hungary and Poland, to name only the most obvious.

- The second force is resentment against the remote elites who have exploited the upside of globalisation while cunningly protecting themselves against the downside. They include borderless bankers who suddenly rediscover the importance of nation-states when it comes to bailing out their banks, and international networkers who, in the words of Thierry Baudet, a hot new populist in the Netherlands, are forever “failing upwards”.

- The pinstriped populist has also made use of a third global force: a technological revolution that is making it easier to create just-in-time political parties out of thin air and keep in constant contact with their supporters….RTWT

Could next week’s European Parliament elections lead to a grand realignment of the continent’s politics, with the populist right wielding unprecedented influence? Hungary’s pugnacious and controversial prime minister, Viktor Orban, certainly hopes so, says analyst Andrew MacDowall.

Could next week’s European Parliament elections lead to a grand realignment of the continent’s politics, with the populist right wielding unprecedented influence? Hungary’s pugnacious and controversial prime minister, Viktor Orban, certainly hopes so, says analyst Andrew MacDowall.

Poland’s de facto leader, Jaroslaw Kaczynski, the head of the ruling, arch-conservative Law and Justice party, PiS, is also eyeing the leadership of an invigorated right. So too Italy’s deputy prime minister, Matteo Salvini, the figurehead for a potential new populist bloc aiming to reconstitute European politics, he writes for World Politics Review:

But even if they all do as well as predicted next week, with far-right, populist and other euroskeptic parties projected to win around a quarter to a third of the seats in the European Parliament, the question remains: Can the disparate forces of Europe’s populist right coalesce into a coherent whole and put their plans into action? ……. A populist uprising might make for an attractive narrative, but it doesn’t match the reality of intra-populist divisions—to say nothing of the eclectic mix of parties, reflecting a wide range of issues, that voters will send to the next European Parliament.

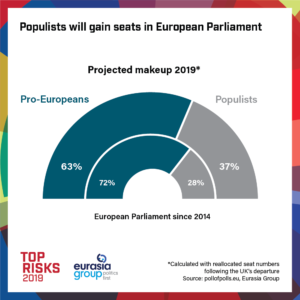

Populists are poised to make gains in the European Parliament polls, according to analysts, including the Eurasia Group (above).

There are a number of different things going on across the European Union’s 28 electorates, including fragmentation of the old class-based political order; the emergence of new populist forces; and there are the usual national ‘counter-cyclical’ dynamics of voters wanting to punish their incumbent government, the BBC reports.

There are a number of different things going on across the European Union’s 28 electorates, including fragmentation of the old class-based political order; the emergence of new populist forces; and there are the usual national ‘counter-cyclical’ dynamics of voters wanting to punish their incumbent government, the BBC reports.

“The central problem of social democracy is simple…. They’ve got to have a narrative about the future,” former UK prime minister Tony Blair said:

By his formulation then, the crisis of Europe’s centre-left may have been long and painful, but it need not be terminal. Finding that new narrative in a way that works across dozens of European electorates, is another matter entirely. Certainly it won’t happen before the European election starting on 23 May, where the centre-left may well find itself trailing the populist right….Matteo Renzi, the former Italian PM, told Newsnight the fortunes of his Democratic Party are now a secondary matter.

“Maybe we will be back, maybe not. This is not my priority,” he said. “My priority today is a great cultural fight against populism.”

Opposition from within civil society presents a difficulty for populists: it potentially undermines their claim to be the sole representatives of the people, argues Princeton University’s Jan-Werner Müller.

Opposition from within civil society presents a difficulty for populists: it potentially undermines their claim to be the sole representatives of the people, argues Princeton University’s Jan-Werner Müller.

Their method of dealing with this problem is to follow a playbook perfected by Vladimir Putin (in many ways a role model for today’s right-wing populists): set out to ‘prove’ that civil society isn’t civil society at all, and that what appears to be popular opposition on the streets has nothing to do with the real people, he writes for The London Review of Books:

Thus right-wing populist regimes have gone out of their way to discredit NGOs, representing them as the tools of external powers, and even (in Russia) insisting they declare themselves as ‘foreign agents’. …..But for the truly creative conspiracy theorist there are no limits: the Gezi Park protests of 2013, an Erdoğan adviser eventually revealed, were the doing of Lufthansa, which allegedly feared increased competition from Turkish Airlines after the opening of Istanbul’s new airport. At the same time, populists may come to relish protest: it puts fuel on the fire of the culture wars on which they thrive.

“The lesson here is not, of course, that citizens shouldn’t take to the streets to protest, only that they ought to be aware of how swift and sophisticated populists can be in turning dissent to their own advantage, to justify what always ends up as a form of exclusionary identity politics,” adds Müller, author of What is Populism?

The credibility of democracy suffers from a temporal contradiction, Carlo Bastasin writes for Brookings’ Democracy and Disorder series:

The credibility of democracy suffers from a temporal contradiction, Carlo Bastasin writes for Brookings’ Democracy and Disorder series:

If a government wants to, it can correct inequality in just a few months by changing tax levels and enacting redistributive policies. However, it takes many years, and sometimes decades are not enough, to correct the divergence, de-industrialization, or obsolete knowledge and technologies. If this unprecedented temporal contradiction between the popular vote and the solution to problems is not made explicit, then democracy, its cycles, and even its language will become worthless in the eyes of citizens.

The celebrated sociologist Nathan Glazer displayed a remarkable consistency throughout his life: He was an opponent of totalitarianism and authoritarianism whether it took form on the right or on the left, Alan Wolfe writes for The New Republic:

Last year I published a book called The Politics of Petulance in which I identified Glazer and his fellow intellectuals as “mature liberals.” “I like the idea of ‘mature liberals,’” Nat emailed me shortly before he died, “despite my identification as a neocon I still consider myself a liberal. But neocon now has become the identification of an activist and belligerent stance in foreign policy I don’t share. I will call myself a “mature liberal” in future, if I have occasion to call myself anything…” Alas, no such occasion presented itself.

Last year I published a book called The Politics of Petulance in which I identified Glazer and his fellow intellectuals as “mature liberals.” “I like the idea of ‘mature liberals,’” Nat emailed me shortly before he died, “despite my identification as a neocon I still consider myself a liberal. But neocon now has become the identification of an activist and belligerent stance in foreign policy I don’t share. I will call myself a “mature liberal” in future, if I have occasion to call myself anything…” Alas, no such occasion presented itself.

The historical record since 1945 gives us a picture of how populists operate once they hold political power. The record shows that populism is inimical to liberal democracy, and not a corrective to some of its failings, Takis S. Pappas writes for the National Endowment for Democracy‘s Journal of Democracy.