NDI

It will take more than one election cycle to get democracy to satisfy the expectations of the Lebanese people, according to Louisa Slavkova and Rob Norris, who served as National Democratic Institute election observers in the country’s recent elections. Democracy is an endeavor of small steps and considerable patience.

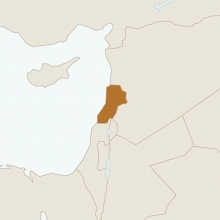

“A good place to understand the present, and to ask questions about the future, is on the ground, travelling as slowly as possible,” according to Robert Kaplan’s The Revenge of Geography, which explains why geography is crucial for understanding frontiers – cultural and political – especially where they are contested.” Our small team of election observers, deployed to the regions of West Beqaa and Rachayia in Lebanon, often confronted such geography lessons and borders, while trying to grasp the complexities on the ground.

“This is the Golan Heights. Over there is Palestine,” the first party candidate we met told us, “and this is Mount Hermon,” he continued pointing to the hill a mile away, from the window of his office. “You see this neighborhood isn’t very easy, just like the entire country.”

“The first thing we are going to work on after the elections is the new electoral law. It made parties do impossible coalitions to form a party list and same-party candidates to run against each other. This type of competition isn’t healthy,” the candidate continued. “It further exacerbates the focus on the candidates and less so on political platforms.”

Cab drivers and analysts alike confirmed this privately shared assessment: during the campaign all candidates claimed to be the only ones who can improve conditions in Lebanon, but hardly anyone had mapped a vision of what should be done and how it should be achieved. “I hope for disruption in the political system, for a new mentality of a younger generation of politicians, who work beyond religious divides and focus on the well-being of the citizens,” [said whom?] Both our interlocutor and ourselves left the meeting without an answer to the question as to where to find the new generation of Lebanese politicians. The loud voices of party agents, supporters, and citizens who’d gather in the politician’s yard to express their support became a distant noise as we drove on our way up north.

Cab drivers and analysts alike confirmed this privately shared assessment: during the campaign all candidates claimed to be the only ones who can improve conditions in Lebanon, but hardly anyone had mapped a vision of what should be done and how it should be achieved. “I hope for disruption in the political system, for a new mentality of a younger generation of politicians, who work beyond religious divides and focus on the well-being of the citizens,” [said whom?] Both our interlocutor and ourselves left the meeting without an answer to the question as to where to find the new generation of Lebanese politicians. The loud voices of party agents, supporters, and citizens who’d gather in the politician’s yard to express their support became a distant noise as we drove on our way up north.

As we were approaching our destination, we saw more and gated security checkpoints, and the military presence became more prominent. We soon found ourselves pass by a sign for the Syrian border. The small village we visited had fewer than 500 citizens and a Syrian sister village on the other side of the small valley. The dialect spoken there was closer to Syrian Arabic than to Lebanese. We had received information that campaigning here was tough as the local candidate didn’t tolerate much competition. In an attempt to verify that information, we drove around a small and rather empty but picturesque place, looking for the polling station. In the midday heat, we greeted the security guards at the only polling center, who were hanging a large banner of the local candidate on the building’s exterior. Our presence prompted them to hastily remove the banner.

As we were approaching our destination, we saw more and gated security checkpoints, and the military presence became more prominent. We soon found ourselves pass by a sign for the Syrian border. The small village we visited had fewer than 500 citizens and a Syrian sister village on the other side of the small valley. The dialect spoken there was closer to Syrian Arabic than to Lebanese. We had received information that campaigning here was tough as the local candidate didn’t tolerate much competition. In an attempt to verify that information, we drove around a small and rather empty but picturesque place, looking for the polling station. In the midday heat, we greeted the security guards at the only polling center, who were hanging a large banner of the local candidate on the building’s exterior. Our presence prompted them to hastily remove the banner.

Western commitment?

Western commitment?

Lebanon held historic elections on May 6, the first in 9 years. Compared to 2009, when the country was buzzing with international observers, this time the election observer mission was limited to a small body of mainly EU and NDI observers, alongside LADE, a local network. We made up one of a dozen NDI teams deployed across the country. The West’s increasing self-absorption has resulted in retreat from places like Lebanon and Western commitment to free and fair elections. Especially in times like these, when we in the Western world are caught up in our own problems with democracy, it is easy to forget that it is in our interest to keep supporting the founding values of democracy abroad.

To complicate matters, over the past seven years, Lebanon has struggled to accommodate up to two million Syrian refugees fleeing the brutality of the Assad regime at home. They now constitute almost one-third of the population. While the conversation in the West about the refugee crisis is often reduced to its humanitarian aspects, the history of the region quickly reminds one of another layer. Syrian forces had occupied Lebanon for more than two decades, and those wounds haven’t healed. It is a miracle that the influx of millions of Syrians hasn’t caused a spill-over of the conflict.

The regions of West Beqaa and Rachayia are a patchwork of refugee camps. Locals tell us stories of the cheap Syrian labor in agriculture, a practice welcomed in an area of fruitful soil and rich crops. We are also reminded of the situation of the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, for decades marked by uncertainties of status, citizenship, and employment. Research suggests that, after a few years of displacement, refugees’ chance of ever going back home shrinks to nil. The question of the fate of the millions of Syrians in Lebanon and elsewhere remains open.

The regions of West Beqaa and Rachayia are a patchwork of refugee camps. Locals tell us stories of the cheap Syrian labor in agriculture, a practice welcomed in an area of fruitful soil and rich crops. We are also reminded of the situation of the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, for decades marked by uncertainties of status, citizenship, and employment. Research suggests that, after a few years of displacement, refugees’ chance of ever going back home shrinks to nil. The question of the fate of the millions of Syrians in Lebanon and elsewhere remains open.

Against this backdrop and the political deadlock in Lebanon over the past decade, the May 6 elections are potentially a historically significant step. Firstly, the country has introduced a new electoral system — a combination of proportional and preference voting. Almost 600 candidates in more than 70 lists run for one of the 128 parliamentary seats, which are equally divided between Christians and Muslims. This allowed for newcomers to enter the political scene and even form platforms that still fit within the confessional quota but claim to be less focused on that and more on people’s demands. Some of them emerged from the protests during the garbage crisis of 2015 and 2016. Secondly, there was a considerable number of female candidates, in a country with one of the lowest rates of female participation in public life and politics.

No one, particularly among the young people of Lebanon, has illusions that the new law is going to dramatically change the realities and, most notably, loyalties on the ground. First-time voters among 21- to 30-year-olds constituted almost 20% of the registered voters. The voter turnout was lower than in 2009, pointing to citizens’ disappointment with their political class and the lack of significant alternatives.

Clientelism

Clientelism

Even though it was election time — and despite the small irregularities, the ballot was conducted according to the rules — one couldn’t escape the feeling that it was highly transactional and predetermined. Casting one’s vote was almost a symbolic gesture of confirming both one’s religious orientation and dependency.

Bulgaria, where one of our two-person team comes from, has a comparatively short democratic track record of less than 30 years, and many of the reported election irregularities in Lebanon still occur in Eastern Europe. But the level of clientelism in some parts of West Beqaa and Rachayaia is something we hadn’t witnessed before. One of the party candidates we met spent most of our meeting answering phone calls by citizens who were reassuring him they were going to vote for him. On election night, we passed by his home where hundreds of people had gathered to congratulate him on his victory and, as our young assistant told us, “to remind him not to forget they gave his vote for him.” The party agents present in large numbers at each polling station diligently ticked off every voter from their lists, making it easy, especially in smaller communities, to identify who didn’t cast their vote.

One evening we got into a discussion with a young woman who was determined to stay home on election day. She explained that she didn’t see a point in elections because there wasn’t a real choice. In her words, she couldn’t even go to university without her parents calling their candidate to pull strings. The practice of clientelism goes beyond what one would call cultural differences or nuances of practice. Clientelism paired with the strictly defined sectarian quotas creates dependencies and bonds that are based on a short-term profit for both voters and politicians. It leaves citizens with no real alternative and discourages politicians from working through convincing political programs for people’s votes.

Confessional balance

Lebanon’s political system mirrors the delicate confessional balance of a country that has probably seen more conflict than peace since its declaration of independence after WWII. Its multiethnic and religious composition is both a blessing and a curse. A significant body of research suggests that it isn’t that certain cultures and religions are less prone to democratic rule, but that heterogeneity makes it more difficult for democracy to grow.

Lebanon’s political system mirrors the delicate confessional balance of a country that has probably seen more conflict than peace since its declaration of independence after WWII. Its multiethnic and religious composition is both a blessing and a curse. A significant body of research suggests that it isn’t that certain cultures and religions are less prone to democratic rule, but that heterogeneity makes it more difficult for democracy to grow.

The complicated political system and the newly passed electoral law highlight the struggle to reconcile the deeply institutionalized confessional divides with growing citizens’ demands to go beyond them for the sake of building working institutions and passing policies that actually deliver. The parliamentary seats to be determined by these elections are equally divided between Christians and Muslims following the agreement reached after the Civil War and based on population estimations and a census from the 1930s.

It will take more than one election cycle and more than one amendment to the electoral law to get democracy up and running and satisfy the expectations of the Lebanese people. Democracy is an endeavor of small steps and large amounts of patience. Just as we believe that small acts like our presence prevented a campaign poster from hanging in a polling center and contributed to a more equal, freer election process, we wish to believe that the May 6 elections rejuvenated the Lebanese democracy. Only a robust democratic process can guarantee the prosperity of the Lebanese people in a neighborhood so complicated as the Middle Eastern.

Louisa Slavkova is co-founder and director of Sofia Platform, a democracy resilience NGO. She was adviser to Bulgarian minister of Foreign Affairs Nickolay Mladenov and a Ronald Lauder visiting fellow at the Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University. Rob Norris is former member of the Saskatchewan Legislature and former Saskatchewan cabinet minister, Rob Norris serves as a senior strategist at the University of Saskatchewan, is the Chair of Canada World Youth as well as Bangladesh’s Hon. Consul in Saskatchewan, Canada. Both served together as NDI election observers in Tunisia (2014) and most recently in Lebanon.