A senior US intelligence official has labeled China the biggest threat to democracy and freedom worldwide since the Second World War, saying it was set on global domination.

“The intelligence is clear: Beijing intends to dominate the US and the rest of the planet economically, militarily and technologically,” John Ratcliffe, the director of national intelligence, said in an opinion article in the Wall Street Journal. China posed “the greatest threat to America today, and the greatest threat to democracy and freedom worldwide since world war two”, he added.

TONIGHT: Join @NEDemocracy @CanEmbUSA for the seventeenth annual Seymour Martin Lipset Lecture on Democracy in the World featuring China scholar and @CMCnews professor Minxin Pei https://t.co/DdlvSZftSm #NEDEvents pic.twitter.com/tPyL81w4XD

— NEDemocracy (@NEDemocracy) December 3, 2020

To the extent that President Xi Jinping wants China to rule the world, the challenge to the US is serious. For the EU, the danger is existential, notes one observer. Xi seems to have been doing his best of late to disabuse those who still argue that China will respect the liberal international order. The rhythm of his regime has settled into one of voluble disdain for “western” rules and studied aggression towards supposed adversaries, notes FT analyst Philip Stephens:

Australia dared support an independent inquiry into the outbreak of Covid-19; it now finds itself under sustained economic onslaught. Canada’s detention of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in response to an extradition request from US authorities was met with the arrest of two Canadian citizens on alleged espionage charges. A pro-independence government in Taiwan is threatened with reunification by force. The embers of democracy in Hong Kong have been snuffed out. Vietnamese fishing boats are harassed in the South China Sea.

The EU is what political scientists call a “normative” power: it exercises leadership by example. It will not survive in a world of Beijing’s design, where cherished rules are replaced by the will of the mighty, Stephens concludes.

Europe must take sides with the US over China https://t.co/R41mRq10lZ via @financialtimes

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) December 3, 2020

But competition with China need not require confrontation or a second cold war, according to Kurt M. Campbell, former Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia and Pacific Affairs, and Rush Doshi, Director of the Brookings Institution’s China Strategy Initiative and the author of a forthcoming report on China’s global information influence operations.

The United States has a responsibility to protect Asian Americans from discrimination, and it must avoid conflating the Chinese Communist Party with the Chinese people or with Chinese Americans by sending a clear and early message that demagoguery and racism are unacceptable, they write for Foreign Affairs:

With a constructive China policy that strengthens the United States at home and makes it more competitive abroad, American leaders can begin to reverse the impression of U.S. decline. But they cannot stop there. They must also find affirmative ways to rebuild the solidarity and civic identity that make democracy work. An effort to stress a shared liberal nationalism, or what the historian Jill Lepore calls a “New Americanism,” has been part of our civic culture and can be again.

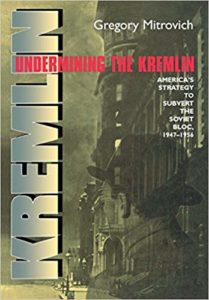

Today’s conflict between the United States and China is considerably different from the U.S.-Soviet Cold War, argues a research scholar at the Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University and author of “Undermining the Kremlin: America’s Strategy to Subvert the Soviet Bloc, 1947-1956.” Unlike the USSR, China lacks a powerful ideology to foster worldwide insurgency movements. With China’s advancements in 5G cellular technology and artificial intelligence, the real hegemonic battle will be fought in the realms of international trade, finance, development and technology, he writes for the Post:

Today’s conflict between the United States and China is considerably different from the U.S.-Soviet Cold War, argues a research scholar at the Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University and author of “Undermining the Kremlin: America’s Strategy to Subvert the Soviet Bloc, 1947-1956.” Unlike the USSR, China lacks a powerful ideology to foster worldwide insurgency movements. With China’s advancements in 5G cellular technology and artificial intelligence, the real hegemonic battle will be fought in the realms of international trade, finance, development and technology, he writes for the Post:

Nevertheless, the Cold War playbook could help the United States counter China today. The United States could act to convince the world of the superiority of the West’s democratic, free-market system, expose the debt traps created by China’s Belt and Road Initiative, discredit the Chinese dream and convince the Chinese that being a “responsible stakeholder” in the international community would best enable their nation’s continued, peaceful rise as a great power.

In the global trend of democratic backsliding, Hong Kong provides an illustrative case of how democratic institutions could be degenerated by “exporting autocracy”, a new analysis suggests.

After 1997, Hong Kong’s semi-democracy has come under continuous pressure by China’s extra-jurisdictional autocratic influence, Brian C.H. Fong writes for Democratization. When about two decades of exporting autocracy has almost made Hong Kong a semi-democratic façade, China imposed the National Security Law in June 2020 placing the last straw that breaks its semi-democracy. The case study of Hong Kong offers comparative observations about China’s exporting autocracy across its surrounding jurisdictions in the Asia-Pacific region.

SEVENTEENTH ANNUAL SEYMOUR MARTIN LIPSET LECTURE: MINXIN PEI ON “TOTALITARIANISM’S LONG DARK SHADOW OVER CHINA”