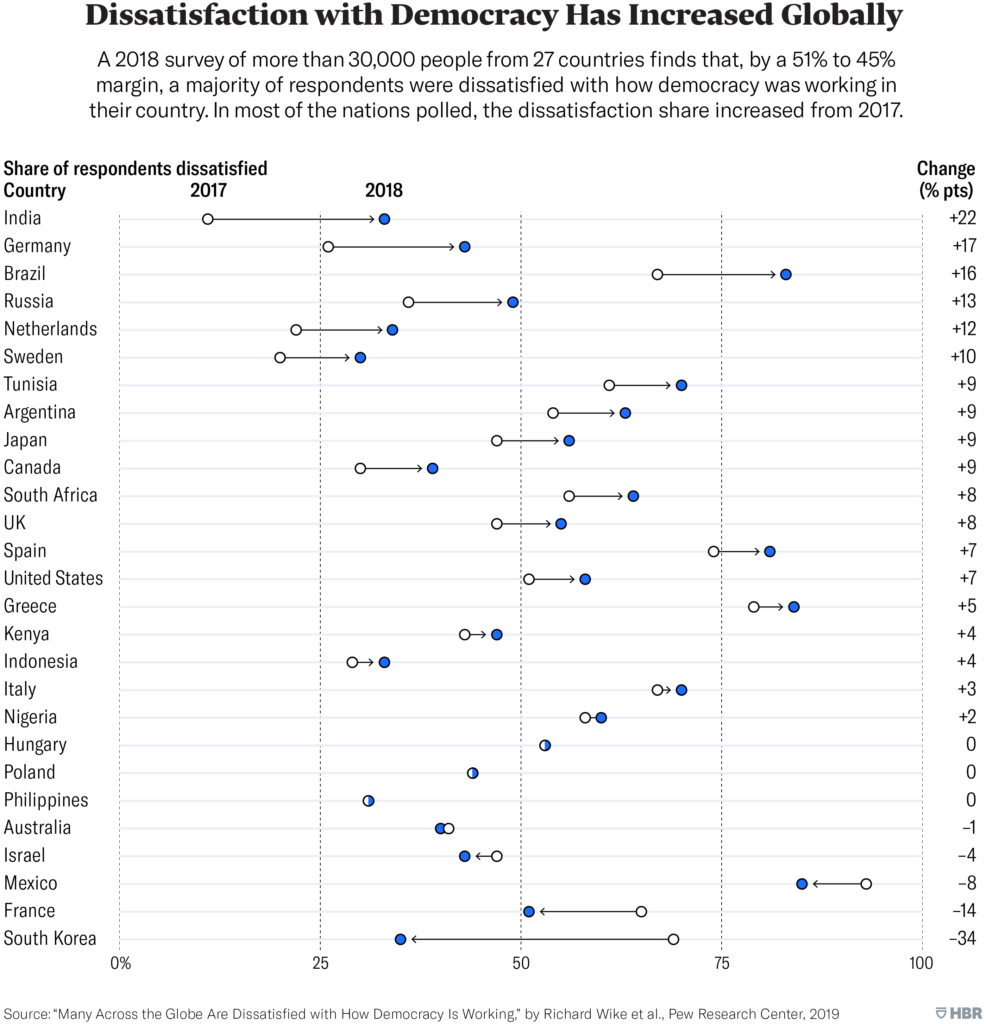

Dissatisfaction with democracy has increased worldwide, a recent Pew Center report observed, with only 45% of people stating that they are “satisfied with the way democracy is working in their country.”

Without democratically accountable governments to ensure that markets remain free and fair; that “externalities” like pollution are properly controlled; and that opportunity is available to all, societies risk falling into populism, argues Rebecca Henderson, the John and Natty McArthur University Professor at Harvard University, and author of the book, Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire.

Without democratically accountable governments to ensure that markets remain free and fair; that “externalities” like pollution are properly controlled; and that opportunity is available to all, societies risk falling into populism, argues Rebecca Henderson, the John and Natty McArthur University Professor at Harvard University, and author of the book, Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire.

In countries around the world, left-wing populists are experimenting with state control, and right-wing populist governments are degenerating into crony capitalism (or worse). Neither is good for business, and both will have horrible effects on our society and the planet.

Harvard Business Review

Democratic government protects and strengthens free markets by providing (at least!) four of the essential pillars of genuinely free and fair capitalism,* she writes for the Harvard Business Review:

- An impartial justice system. Free markets require property rights and contracts, which protect everything from land and potatoes to ideas and information. They also rest on the understanding that participants in the market will keep their promises — and that if they don’t, there will be consequences. Both things depend on the rule of law. Without it, corruption flourishes: Property rights change hands at the whim of the powerful; contracts are not worth the paper they’re printed on. No legal system is ever completely impartial or effective, of course, but countries in which the government is democratically accountable tend to have much stronger and less corrupt judicial systems.

- Prices that reflect true costs. Prices allow thousands of buyers and sellers to work together without the need for formal coordination — a daily miracle that creates global prosperity. Milton Friedman spoke eloquently about how the price mechanism works to facilitate the hundreds of transactions — among “people who don’t speak the same language, who practice different religions, who might hate one another if they ever met” — required to make something as simple as a pencil. But prices work their magic only when they reflect the intersection between real costs and a real willingness to pay…. If markets are to be efficient, they need governments to ensure that externalities are properly priced — in this case, for example, by taxing carbon emissions and pollution.

-

Center for International Enterprise (CIPE)

Real competition. Markets are only free and fair when it’s easy to enter and leave them, and when participants are prevented from colluding. When this is the case, competition thrives, forcing firms to adopt the latest techniques and to improve efficiency and productivity. It drives them to innovate, propelling the cycle of “creative destruction” that political economist Joseph Schumpeter celebrated …. It was government that broke up AT&T and IBM, triggering an explosion of competition and greatly reducing prices. It will almost certainly be government that ensures that there is genuine competition for companies like Amazon, Google, and Facebook.

- Freedom of opportunity. Last but not least, markets are genuinely free only when everyone can play. When the economy is controlled by the state or the political elite, the opposite is true: Access to jobs and economic opportunity is tightly controlled. Relatives of the rich and powerful can start firms, but you can’t. Finding a job is a matter of connections and access — of going hat in hand to those who control the levers of power.

The form of capitalism that prevailed in the West from the end of World War II until the fall of communism was “social-democratic capitalism,” former World Bank economist Branko Milanovic writes in Capitalism Alone: The Future of the System that Rules the World. He uses the term broadly to include not just the authentic social democracies of Europe but also the United States of the New Deal and Great Society, which similarly expanded the middle class and reduced inequality, notes Arthur Goldhammer, an affiliate of Harvard’s Center for European Studies. But social-democratic capitalism has been in retreat everywhere for several decades now, with consequences for the distribution of wealth and income, as well as for democracy itself, that cannot be ignored, he writes for Democracy: A Journal of Ideas:

What was once a democracy comes more and more to resemble an oligarchy, which justifies its class structure through the ideology of meritocracy—that is, the belief that the rich are rich because they are also the best, brightest, and most industrious. Yet the real source of the political influence of the wealthy is not that they have better ideas about how to organize society but, quite simply, that they have more to spend on acquiring power…..

What was once a democracy comes more and more to resemble an oligarchy, which justifies its class structure through the ideology of meritocracy—that is, the belief that the rich are rich because they are also the best, brightest, and most industrious. Yet the real source of the political influence of the wealthy is not that they have better ideas about how to organize society but, quite simply, that they have more to spend on acquiring power…..

Furthermore, people are increasingly aware that the influence of billionaires has grown to proportions that are worrisome for democratic institutions, which are also threatened by the rise of inequality and “populism,” Capital and Ideology author Thomas Piketty writes for Fast Company.

The key distinction business needs to make is between civics and politics, Henderson suggests. Rather than taking a partisan position (or spending money) on specific policies, firms should instead focus on the policy-making process, actively supporting a healthy, functioning democracy so that all stakeholders and communities can engage in active debate about what those policies should be. RTWT

The key distinction business needs to make is between civics and politics, Henderson suggests. Rather than taking a partisan position (or spending money) on specific policies, firms should instead focus on the policy-making process, actively supporting a healthy, functioning democracy so that all stakeholders and communities can engage in active debate about what those policies should be. RTWT

*As the Center for International Enterprise (CIPE), a core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), has often observed.