Experts have described Hungary’s Viktor Orbán as a new-school despot, a soft autocrat, an anocrat, and a reactionary populist. Kim Lane Scheppele, a professor of international affairs at Princeton, has referred to him as “the ultimate twenty-first-century dictator,” The New Yorker’s Brian Marantz writes:

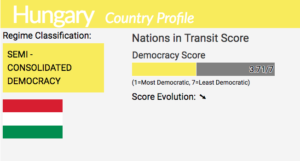

“You do not have to have emergency powers or a military coup for democracy to wither,” Aziz Huq, a constitutional-law professor at the University of Chicago, told me. “Most recent cases of backsliding, Hungary being a classic example, have occurred through legal means.” Orbán runs for reëlection every four years. In theory, there is a chance that he could lose. In practice, he has so thoroughly rigged the system that his grip on power is virtually assured. The political-science term for this is “competitive authoritarianism.” Most scholarly books about democratic backsliding (“The New Despotism,” “Democracy Rules,” “How Democracies Die”) cite Hungary, along with Brazil and Turkey, as countries that were consolidated democracies, for a while, before they started turning back the clock.

Hungary is what Sergei Guriyev and Daniel Treisman describe as an informational autocracy, a new form that characterizes the 21st century, says analyst Peter Kreko. Information autocracies use information as the main tool for manufacturing legitimacy for the regime and changing the behavior of citizens and voters, he tells the Bush Center.

Hungary is what Sergei Guriyev and Daniel Treisman describe as an informational autocracy, a new form that characterizes the 21st century, says analyst Peter Kreko. Information autocracies use information as the main tool for manufacturing legitimacy for the regime and changing the behavior of citizens and voters, he tells the Bush Center.

Information autocracies are special in that they define themselves usually as some kind of democracy, even if the democracy is mostly not liberal and not based on the rule of law, adds Kreko, a former Reagan-Fascell fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

As you know, some in the United States are enamored with the Hungarian model of illiberal democracy. They would argue: “Look, you have Viktor Orban who is popular. He’s carrying out the will of his people. In fact, this is a democracy.” How do you respond to those kinds of opinions? What makes Hungary so concerning? the Bush Institute’s Christopher Walsh and William McKenzie ask.

I am going to give you three examples, says Kreko, head of the Budapest-based Political Capital Institute:

- First, let’s imagine that a U.S. president totally changed the Constitution and put loyalists in all the federal institutions so they are occupied by the people of one administration. The checks and balances would be systemically switched off. In Hungary, the Constitutional Court, which plays a bit of a similar role to the U.S. Supreme Court, is literally full of Fidesz loyalists. This body has been the most important counterbalance to the executive and legislative power. But it has stopped operating as a brake and is more part of the engine. So is the President. So, one element is occupation of the institutional system.

- A second element is occupation of the media. Let’s assume that only the left- or right-wing media dominates the U.S. media system. Practically, 80-90% of the media would be in the hand of the president. What happened in Hungary was a quite remarkable centralization of media. More than 500 media outlets were put in a huge foundation called KESMA. In a country of 10 million people, this organization dominates about 80% of the media. Also, the overwhelming majority of the state advertisement goes to pro-governmental media. …

- The third example is that the state in Hungary interferes in the economy in a quite brutal manner. In some sectors of the Hungarian economy, such as the media, energy, banking, telecommunications, and tourism sectors, state-owned companies and companies close to the highest echelons of power are taking over. A healthy competition in the economy is more and more distorted.

Yet Orbán also has his defenders, like John O’Sullivan, a former adviser to British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who wrote in an essay collection for his Danube Institute that “the death of liberal democracy in Hungary has been greatly exaggerated.”

Yet Orbán also has his defenders, like John O’Sullivan, a former adviser to British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who wrote in an essay collection for his Danube Institute that “the death of liberal democracy in Hungary has been greatly exaggerated.”

Orbán has a popular mandate, he tells The New Yorker’s Marantz. Rather than delegating gay rights, the handling of asylum claims, and other matters of domestic policy to international bodies—with their adherence to such abstractions as “the rule of law”—isn’t it arguably more democratic to simply put them to a vote?

For O’Sullivan, Orbán is not opposed to liberalism, but to “undemocratic liberalism”, which takes decisions beyond the reach of elected parliaments.

In July 2012, the Journal of Democracy published a set of articles analyzing “Hungary’s Illiberal Turn,”3 notes NED board member Marc F. Plattner. The common goal of illiberal, pro- Orbán thinkers like Ryszard Legutko is to conflate liberal democracy with contemporary progressivism and thus to suggest that conservatives should have no interest in supporting or defending liberal democracy, he writes for the JOD.

In July 2012, the Journal of Democracy published a set of articles analyzing “Hungary’s Illiberal Turn,”3 notes NED board member Marc F. Plattner. The common goal of illiberal, pro- Orbán thinkers like Ryszard Legutko is to conflate liberal democracy with contemporary progressivism and thus to suggest that conservatives should have no interest in supporting or defending liberal democracy, he writes for the JOD.

Gabor Miklósi—slightly stooped, perennially tired—is an editor at 444, one of the few independent news outlets left in Hungary, The New Yorker’s Marantz adds:

“He controls most of the national papers, most of the radio and TV stations, all the local papers in the countryside,” Miklósi said. “He doesn’t do it in obvious ways—he does it slowly, by putting his cronies in charge, or by subtly making life difficult for his critics.” …. “Orbán has managed to preserve the appearance of formal democracy, as long as you don’t look too closely,” Anna Grzymala-Busse, the director of the Europe Center at Stanford, told me. Since 2010, most of Hungary’s civic institutions—the courts, the universities, the systems for administering elections—have come to occupy a gray area. They haven’t been eradicated; instead, they’ve been patiently debilitated, delegitimatized, hollowed out. RTWT

@KimLaneLaw, a professor of international affairs at @Princeton, has referred to #Hungary‘s #Orbán as “the ultimate twenty-first-century dictator,” @NewYorker‘s @andrewmarantz writes. https://t.co/Bs422YK4RS via @NewYorker

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) June 27, 2022