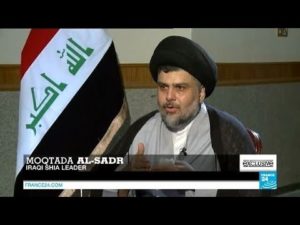

Moktada al-Sadr, the maverick Shiite cleric, who contested the Iraqi elections on an inclusive, nonsectarian list with Communists, independents and liberal civil society groups, has emerged as the winner.. During the campaign, Mr. Sadr promised to fight corruption, work across sectarian lines and bring in technocrats to run the government, notes Iraqi-British journalist Mina Al-Oraibi. Iran immediately sent Gen. Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Quds Force, to Baghdad after the results, to ensure that its influence does not ebb with the formation of the next government, she writes for the New York Times:

Moktada al-Sadr, the maverick Shiite cleric, who contested the Iraqi elections on an inclusive, nonsectarian list with Communists, independents and liberal civil society groups, has emerged as the winner.. During the campaign, Mr. Sadr promised to fight corruption, work across sectarian lines and bring in technocrats to run the government, notes Iraqi-British journalist Mina Al-Oraibi. Iran immediately sent Gen. Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Quds Force, to Baghdad after the results, to ensure that its influence does not ebb with the formation of the next government, she writes for the New York Times:

[But] Mr. Sadr’s strong performance ensures that Tehran cannot have a new Iraqi government entirely beholden to it. Iran-backed P.M.F. and their allies will seek to carve out a position of power, emulating Lebanon’s Hezbollah. The P.M.F. has rejected efforts to be integrated into Iraqi forces. They want to remain a separate institution, keeping their arms while wielding political power as a bloc in Parliament, where they can use “veto power” to stall, block, and thwart legislation to cripple the government — another lesson learned from Hezbollah.

Sadr won by allying his mass following in the Shia underclass with the Iraqi Communist party and secular civil society groups, the FT adds:

Soleimani (right), the revolutionary guard commander who oversees Iran’s Shia Arab paramilitary allies across the region, is in Iraq trying to put together an alliance with Mr Amiri’s PMF front and the discredited Mr Maliki at its core. Mr Sadr, who wants the US and Iran out of Iraq and has built bridges to Saudi Arabia, is suspect in Iranian eyes. Yet Iraq’s reconstruction and very survival need wide consensus and competent ministers, which argues for the inclusion of the Sadrist coalition and Mr Abadi.

Soleimani (right), the revolutionary guard commander who oversees Iran’s Shia Arab paramilitary allies across the region, is in Iraq trying to put together an alliance with Mr Amiri’s PMF front and the discredited Mr Maliki at its core. Mr Sadr, who wants the US and Iran out of Iraq and has built bridges to Saudi Arabia, is suspect in Iranian eyes. Yet Iraq’s reconstruction and very survival need wide consensus and competent ministers, which argues for the inclusion of the Sadrist coalition and Mr Abadi.

Amid low turnout in Iraq’s elections, the Sadrists’ active voter base helped them win Baghdad, weakening Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s prospects for reelection, argues Kirk H. Sowell, the principal of Utica Risk Services, a Middle East-focused political risk firm. Sadr’s success is due more to the mechanics of base mobilization and coalition management than any dramatic increase in support per se, he writes for Carnegie’s Sada Journal:

The most likely scenario, Abadi’s reelection with Sadr’s support, will produce a different political dynamic than under the last term, but not a radically different set of policies. As before, Abadi will lack a stable majority in parliament that would facilitate passing legislation. Given the populist bent of his new allies, this would in particular make getting the budget and associated economic reforms passed even more difficult.

The most likely scenario, Abadi’s reelection with Sadr’s support, will produce a different political dynamic than under the last term, but not a radically different set of policies. As before, Abadi will lack a stable majority in parliament that would facilitate passing legislation. Given the populist bent of his new allies, this would in particular make getting the budget and associated economic reforms passed even more difficult.

The bottom line is that a Sadr-Abadi coalition will not yield the necessary dividends: Baghdad is too volatile, unpredictable, and fragmented for Washington to continue investing in al-Abadi as though it is business as usual, argues Ranj Alaaldin, a Visiting Fellow at the Brookings Doha Center:

Were al-Abadi to win another term, he would return severely weakened and subsumed by the staunchly anti-American Muqtada al-Sadr and the PMF. That will not change anytime soon and any attempt to paint it otherwise is wishful thinking, if not a dangerous miscalculation that will have costs down the line for the United States and its allies.

Credit: FT

The election results were dramatic but unsurprising. For several years now, Iraqis were telling anyone who would listen that they felt betrayed by their leadership for its corruption, indolence, and callous disregard for their misery, writes AEI’s Kenneth Pollack:

Even in early 2016, I had found that Iraq’s three primary communities had become badly divided in their primary interests, and all of them felt alienated from the elite. Iraq’s Shi’a Arab community was focused on government reform, curbing corruption, and improving public services. Its Sunni Arabs wanted money for reconstruction, better political representation, and their fair share of Iraq’s economic benefits. And the Kurds wanted independence, in part for historical-cultural reasons and in part because they were sick of being treated like second-class citizens by the rest of Iraq.

IRI

Whatever the headlines, the United States should feel neither disappointed by nor fearful of the results thus far, adds Michael Knights, who has worked in all of Iraq’s provinces and covered all the country’s elections since 2005. A stronger public endorsement of Haider al-Abadi’s moderate, progressive vision for Iraq would have been reassuring for the United States and other Western allies of Iraq, but certain realities must be borne in mind, he writes for the Washington Institute for Near East Policy:

No result at the polls and no government-formation process can ensure U.S. interests in Iraq: the protection of U.S. interests is a never-ending process, not a quadrennial event. Abadi—or any other Iraqi prime minister—should be judged on what he does, not who he is. The United States, meanwhile, should remain focused on its core interests in Iraq—stability and openness to partnership—which are best served by a leader who will be inclusive toward all Iraq’s communities, pursue smart counterterrorism policies, support economic reforms, keep Iraq neutral amid the region’s tensions, and explore the potential inherent in the U.S.-Iraq Strategic Framework agreement, signed in 2008.