Democracies have a significant advantage in weaponizing transparency at scale to highlight autocratic activities that break international norms or inflict damage on local economies and populations, argue Garrett Berntsen, the Deputy Chief Data Officer at the U.S. Department of State, and Ryan Fedasiuk, an adjunct fellow at the Center for a New American Security.

Democracies have a significant advantage in weaponizing transparency at scale to highlight autocratic activities that break international norms or inflict damage on local economies and populations, argue Garrett Berntsen, the Deputy Chief Data Officer at the U.S. Department of State, and Ryan Fedasiuk, an adjunct fellow at the Center for a New American Security.

As the saying goes, sunlight is the best disinfectant, they write for War On The Rocks. Democratic governments can take three steps to better weaponize transparency: streamlining the ways they currently collect and publish data, funding public-private partnerships to harvest more of it, and encouraging a cultural shift within their intelligence network:

- First, democratic governments should streamline access to their own unclassified data holdings. ….While the volume and scope of the data collected by the U.S. government has exploded, what has not kept pace is the ability to structure, clean, store, and easily share unclassified data with the public. This is a missed opportunity because much of the data collected and analyzed by national security agencies — by some estimates, as much as 80 percent — is unclassified. Yet, in 2022, the key manner by which the U.S. government shares data and analysis remains massive PDF files strewn across hundreds of individual agency websites. This antiquated approach makes it harder for a growing ecosystem of industry, think tanks, foreign allies, international civil society, and nonprofits to utilize the underlying data for their own specific needs, research, and applications.

Second, democracies can lean on civil society to widen the net of public data collectors. Academic research centers like William and Mary’s AidData, the University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, and Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology have contributed tremendous value to public, private, and government researchers alike. With relatively minimal government funding, these and other disaggregated research centers can produce high-quality data that can be bought once and used many times. ……

Second, democracies can lean on civil society to widen the net of public data collectors. Academic research centers like William and Mary’s AidData, the University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, and Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology have contributed tremendous value to public, private, and government researchers alike. With relatively minimal government funding, these and other disaggregated research centers can produce high-quality data that can be bought once and used many times. ……- Finally, a strategy built on weaponizing transparency will necessitate buy-in from intelligence agencies, the Defense Department, and the State Department. Critics of this new paradigm of openness will push back against the additional risk to sources and methods that greater information and data sharing with the public may create. This is a risk that must be taken seriously, but that clear policy frameworks and better classification guidance can help mitigate. Over-classification has been a serious problem across the national security enterprise for decades, with little common sense applied to the question of what cannot be shared and why. This hinders both internal government operations and any ability to rapidly share data externally to non-government organizations.

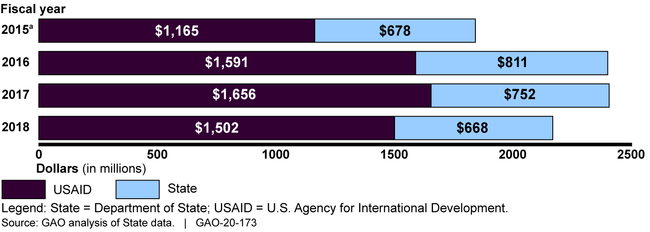

Credit: GAO

One of the chief criticisms of U.S. aid programs is that separate streams of U.S. foreign aid

funding—on education, on countering extremism, on health, on economic support—are

effectively siloed and operate independently from one another. Another criticism is that most

U.S. foreign aid packages are launched after crises occur, in a reactive way that relies on short-term scrambles to fight fires wherever they flare up in the world, according to Foreign Policy’s Robbie Gramer and Mary Yang.

The Global Fragility Act seeks to change that, authorizing around $200 million per year over a

The Global Fragility Act seeks to change that, authorizing around $200 million per year over a

10-year strategy in five pilot programs aimed at integrating all aspects of foreign aid into one

coherent strategy and stabilizing at-risk countries before crises occur, Gramer and Yang write for Foreign Policy:

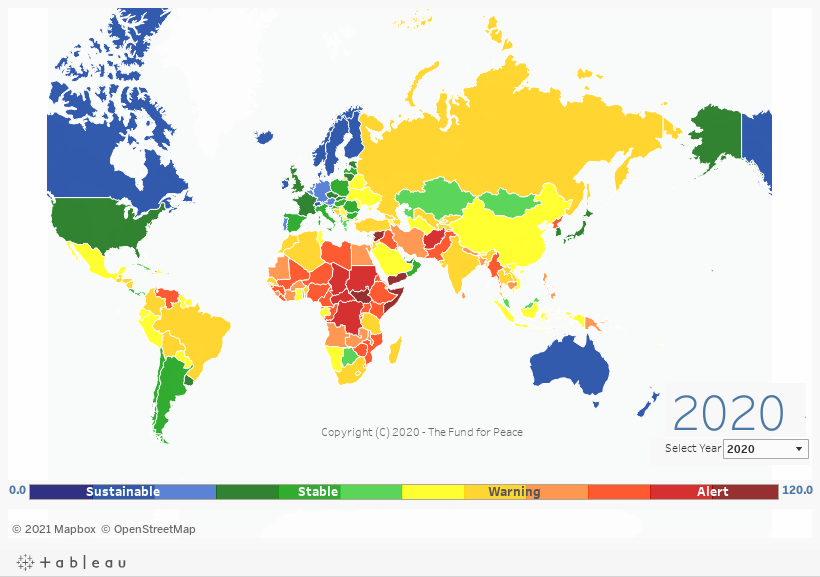

Under the Global Fragility Act, the Biden administration was tasked with picking four pilot

countries and one region to start new programs aimed at tackling the root causes of fragility and political instability. It announced those picks in April: Haiti, Libya, Mozambique, Papua New

Guinea, and a grouping of five Coastal West African countries (Benin, Ivory Coast, Ghana,

Guinea, and Togo) that will take part in the revamped U.S. strategy….There is also creeping pressure to move quickly on the Global Fragility Act when it comes to the United States’ mounting efforts to compete with China geopolitically in conflict-prone regions and showcase Washington as a long-term partner of choice in aid and development over Beijing.

“The Chinese are running circles around the U.S. when it comes to engagement assistance, loans programs in Africa,” said NED’s Peterson, who estimated that China is spending at least 10 times as much as the United States is in Africa. “They’re cultivating relationships in Africa, they’re winning goodwill,” he said. “They are very forward looking.”

The failure of aid to create faster development is a political failure, not an economic one, argues Greg Mills in his latest book, Expensive Poverty: Why aid fails and how it can work.

The failure of aid to create faster development is a political failure, not an economic one, argues Greg Mills in his latest book, Expensive Poverty: Why aid fails and how it can work.

The director of the Brenthurst Foundation, a South African think-tank funded partly by the Oppenheimer family, draws attention to “the empirical congruence between democracy and development in Africa”, citing Ghana, Senegal, Kenya as examples of democracy delivering accelerated growth, notes Nick Westcott, Director of the Royal African Society.

The more democratic a government, the more answerable it is to its citizens, and the greater the accountability for decisions and spending, he writes for African Arguments. Though corruption undoubtedly exists in these countries, it can be more easily exposed and contained. Where leaders or the political elite feel that they can act with impunity, that is where the scale of corruption escapes all bounds, and the difficulties of spending aid productively are compounded.

#Democracies have a significant advantage in weaponizing transparency at scale to highlight #autocratic activities that break international norms or inflict damage on local economies and populations, @BerntsenG & @RyanFedasiuk write @WarOnTheRocks https://t.co/Hw5GHabEjZ

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) August 23, 2022