A nationwide surge of protest has sent a stunning sign that even after one decade under Xi’ Jinping’s autocratic rule, a small and mostly youthful part of the population dares to imagine, even demand, another China: more liberal, less controlling, politically freer. A murmur of dissent that has survived censorship, detentions and official damnation under Mr. Xi suddenly broke into a collective roar, The NYT’s Chris Buckley writes.

“I can regain my faith in society and in a generation of youth,” Chen Min, an outspoken Chinese journalist and writer who goes by the pen name Xiao Shu, wrote in an essay this week. “Now I’ve found grounds for my faith: Brainwashing can succeed, but ultimately its success has its limits.”

The boldest of the disruptors have even demanded an end to political repression in China — a startling and unprecedented challenge to the authoritarian rule of President Xi Jinping, reports suggest.

“This is Xi’s first real test,” said Minxin Pei, a political scientist at Claremont McKenna College. “The choices are very hard, and he’s not been faced with such a tough challenge in the last decade.”

Autocracies — whether in China or elsewhere — are oppressive, but has another autocratic regime ever taken away the rights of so many people to lead a normal life? asks M.I.T. professor Yasheng Huang, the author of the forthcoming book “The Rise and the Fall of the EAST: Examination, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology in Chinese History and Today.”

Autocracies — whether in China or elsewhere — are oppressive, but has another autocratic regime ever taken away the rights of so many people to lead a normal life? asks M.I.T. professor Yasheng Huang, the author of the forthcoming book “The Rise and the Fall of the EAST: Examination, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology in Chinese History and Today.”

China’s social contract, in which the Communist Party would observe certain boundaries in exchange for society observing its own, was instrumental in bringing China from the brink of disaster of the Tiananmen crisis and contributed to economic growth and prosperity, he writes for The Times:

Whether we in the West like it or not, opinion surveys during those years showed that young people in China were more supportive of the government’s nationalistic policy agenda than older residents. Mr. Xi broke that social contract. As early as 2013, his government began to channel bank credits to chronically inefficient state-owned enterprises, at the expense of the private sector. Then his government began to crack down on nongovernmental organizations such as feminist groups and on lawyers who helped rural migrant workers negotiate better wage contracts.

Projection of self, rights and ideas

“It’s like some national subconsciousness that resurfaces,” said Geremie R. Barmé, a scholar in New Zealand who studies dissent in China. “Now it’s resurfaced again, this projection of self and of rights and ideas.”

Credit: RFA

When the CCP’s “performance legitimacy” encounters trouble, so does its ability to rule by fear, adds human rights lawyer Teng Biao. He coined the term “high-tech totalitarianism” to emphasize the effectiveness and pervasiveness of total control in China empowered by artificial intelligence, big data, DNA collection, surveillance cameras, social credit, government-controlled social media, and health codes.

However, the A4 Revolution has shattered people’s assumption that mass protests are unlikely, if even possible, under such unprecedented surveillance. Abandoning the zero-COVID policy will, on the one hand, harm Xi’s legitimacy—and with it the legitimacy of the CCP—and, on the other hand, will motivate the protesters. When protests work, people organize more, he tells Foreign Policy.

“This is Xi’s first real test,” said @NEDemocracy board member & @JoDemocracy contributor @MPEI2014 @CMCnews. “The choices are very hard, and he’s not been faced with such a tough challenge in the last decade.” #ChinaProtests https://t.co/jbIICg3DwZ via @YahooNews

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) December 1, 2022

CCP propaganda about foreign hostilities, deployed to delegitimize dissent during the 2019 Hong Kong protests, has lost persuasive power in the latest protests, The Post adds.

Citizens’ concerns are “nationwide and transcend local, ethnic and class boundaries,” said Chenchen Zhang, an assistant professor at Durham University in Britain. “People across the country have experienced first hand the frustrations and suffering caused by zero covid.”

Xi also has no way to convince the Chinese people to continue buying into his rule, reports suggest. As analysts at Societe Generale wrote last month, China’s economy is “in the gutter.”

That leaves Xi with the one thing authoritarians typically rely on when faced with domestic pressure — more repression to enforce order, as Xi did in Hong Kong. “If they see another round of protests,” analyst Pei said, “they’ll say: Let’s just go back to the good old ways of using overwhelming force to show resolve.”

Yet whatever happens in the coming weeks and months, something important may have changed, Nick Kristof writes for The Times.

“It is so significant, for it’s a decisive breach of the ‘Big Silence,’” said Xiao Qiang (right), the founder and editor of China Digital Times, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). “It’s now public knowledge that the emperor isn’t wearing clothes.”

“It is so significant, for it’s a decisive breach of the ‘Big Silence,’” said Xiao Qiang (right), the founder and editor of China Digital Times, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). “It’s now public knowledge that the emperor isn’t wearing clothes.”

U.S. officials believe the protests that erupted in a number of Chinese cities over the weekend are unlikely to spread or spark a wider movement against Beijing’s authoritarian rulers, according to U.S. government communications obtained by POLITICO:

The communications, from Tuesday, describe the protests — in which thousands have gone into the streets to challenge China’s “zero-Covid” lockdowns — as disparate, unorganized and largely leaderless. That makes it unlikely the demonstrations will lead to a larger or more organized movement, the communications say.

The death of Uyghurs sealed in their apartments in the name of “zero-COVID” in the Urumchi fire on 11/24 triggered this week’s protests across China.

The ruling Communist Party is expanding and exporting domestic repressive techniques employed against Uyghurs, Tibetans and Hong Kongers, as well as labor, environmental and other civil society activists, experts suggest.

The ruling Communist Party is expanding and exporting domestic repressive techniques employed against Uyghurs, Tibetans and Hong Kongers, as well as labor, environmental and other civil society activists, experts suggest.

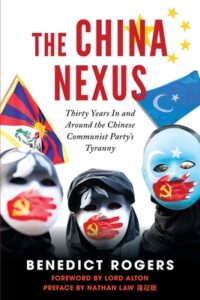

“The CCP is not just a common thread through those issues,” said Benedict Rogers, the author of China Nexus and founder of Hong Kong Watch. “It’s a wake up call to recognize the intensification of oppression within in its borders and aggression outside its borders,” he told yesterday’s NED forum (above).

Rushan Abbas, the founder and executive director of the Campaign for Uyghurs shared her early childhood memories of discrimination against her family. “Four years ago I talked about China’s genocidal policies,” she told the NED event. “My own sister was abducted six days after I exercised my freedom of speech.”

Solidarity

“More and more Hong Kongers have also started to realize we need to build greater solidarity work with Uyghurs, Tibetans, Inner Mongolians, and Taiwanese,” said Alex Chow, Chair of HKDC and co-founder of FLOWHK. “By coming together with different ethnic or racial backgrounds, we are retelling the Chinese story…. retelling what China is.”

Credit: IISS

The protests confirm the emergence of “COVID-1984 – a kind of high tech dictatorship never before seen, the monstrous spawn of the Wuhan virus and Internet technologies,” says the celebrated Chinese writer Liao Yiwu.

Challenging the system

In this week’s protests, “the people of China are speaking on the streets,” said Derek Mitchell, President of the National Democratic Institute. “When people are able to speak freely, we hear what they think. It’s not anti-China to challenge a system based on lies and the fear of truth and freedom,” he told the NED forum.

“The CCP has a project to make the world safe for autocracy and authoritarianism to project all over the world. The future of democracy is tied to the struggle of the Chinese people,” added IRI President Daniel Twining in closing remarks.

The death of Uyghurs sealed in their apartments in the name of “zero-COVID” in the Urumchi fire on 11/24 has triggered protests across China. Today at @NEDemocracy,@benedictrogers @RushanAbbas @alexchow18 discuss the fight for freedom under CCP oppression with @IRIglobal @NDI pic.twitter.com/KXPOCrdeDW

— Damon M. Wilson (@DamonMacWilson) November 30, 2022

Founder & exec. director of Campaign for Uyghurs @RushanAbbas shares early childhood memories of discrimination against her family @CUyghurs #NEDEvents pic.twitter.com/dQFwOCvPxQ

— NEDemocracy (@NEDemocracy) December 1, 2022