In the wake of Beijing’s (supposedly) superior coronavirus-busting effort, Chinese officials and state media outlets have been relentlessly marketing their (authoritarian) governance system as superior, while denigrating the (democratic) U.S. by mocking its pandemic response, notes Michael Schuman, the author of Superpower Interrupted: The Chinese History of the World and The Miracle: The Epic Story of Asia’s Quest for Wealth.

In the wake of Beijing’s (supposedly) superior coronavirus-busting effort, Chinese officials and state media outlets have been relentlessly marketing their (authoritarian) governance system as superior, while denigrating the (democratic) U.S. by mocking its pandemic response, notes Michael Schuman, the author of Superpower Interrupted: The Chinese History of the World and The Miracle: The Epic Story of Asia’s Quest for Wealth.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping intends to build up China’s soft power by pushing Chinese values, both old and new, he writes for The Atlantic. “Facts prove that our path and system … are successful,” he once said. “We should popularize our cultural spirit across countries as well as across time and space, with contemporary values and the eternal charm of Chinese culture.” This is the purpose of Confucius Institutes, a state-run program aimed at promoting Chinese language and culture.

Pundits often describe today’s China as uber-strategic, seeing its every move as carefully coordinated, guided by history and focused on the long run. But Xi’s signature foreign-policy vision, the Belt and Road Initiative, is actually poorly defined and horribly mismanaged. As China pushes ahead with this colossal infrastructure-building spree, it is following in the footsteps of past empires and seriously overreaching, argues Jonathan E. Hillman, the director of the Reconnecting Asia Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the author of “The Emperor’s New Road: China and the Project of the Century“:

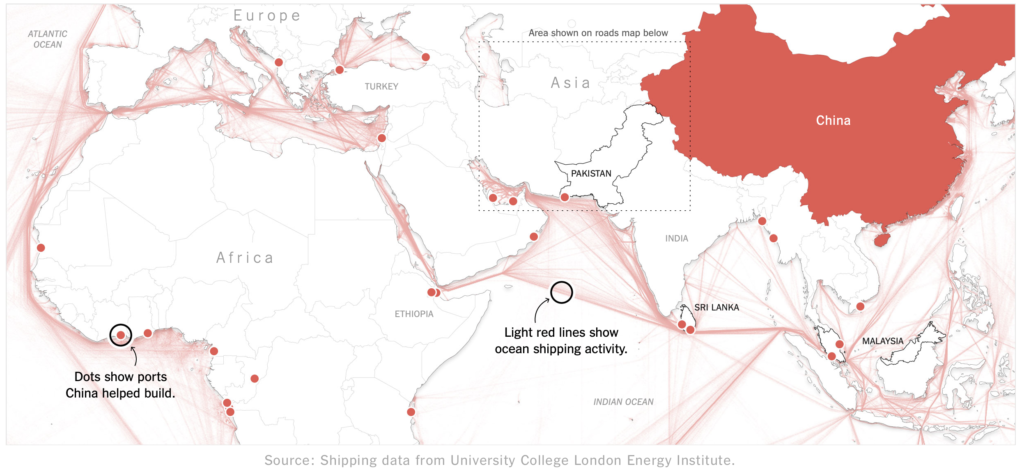

The Belt and Road “is neither a Marshall Plan nor a geostrategic concept,” China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, said in 2018. In fact, it is even more ambitious. The Marshall Plan harnessed the equivalent of $130 billion to rebuild Western Europe after World War II. Since the Belt and Road’s announcement in 2013, China has signed $460 billion in construction contracts across more than 140 countries, according to the American Enterprise Institute.

China is walking into a trap of its own design, he writes for The Wall Street Journal:

Globally, most large infrastructure projects cost more than expected, take longer than expected and deliver fewer benefits than expected, according to Oxford University researchers. To further raise the likelihood of failure, China has picked dangerous partners: Most countries participating in the Belt and Road have sovereign-debt ratings that are either junk or not rated….As in so many earlier imperial adventures, China is struggling to cut its losses, even as fewer new projects are announced. A debt crisis in emerging markets is looming, and historically, most infrastructure booms go bust.

Some other analysts agree with his take…..

Rather than being a coherent, geopolitically-driven grand strategy, BRI is an extremely loose, indeterminate scheme, driven primarily by competing domestic interests, argue analysts Lee Jones and Jinghan Zeng. Rival state capitalist interests, whose struggle for power and resources are shaping BRI’s design and implementation, generate outcomes that often diverge from top leaders’ intentions and may even undermine key foreign policy goals, they write for Third World Quarterly.

Rather than being a coherent, geopolitically-driven grand strategy, BRI is an extremely loose, indeterminate scheme, driven primarily by competing domestic interests, argue analysts Lee Jones and Jinghan Zeng. Rival state capitalist interests, whose struggle for power and resources are shaping BRI’s design and implementation, generate outcomes that often diverge from top leaders’ intentions and may even undermine key foreign policy goals, they write for Third World Quarterly.

In her book, China’s Eurasian Century?, analyst Nadège Rolland speculates that Xi’s long-term vision [embodied in the Belt and Road Initiative] is to create a world order in which Western-style rule of law and democracy promotion are replaced by deference to Chinese interests and the international application of Chinese “stability maintenance” techniques, Columbia University’s Andrew Nathan observed in Foreign Affairs.

China is using its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure fund specifically to promote a system of values different from the West’s, said German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel. Beijing was “constantly trying to test and undermine the unity of the European Union” through a policy of “sticks and carrots,” he added.

Beijing has invested heavily in the BRI and the China Development Bank to advance its discourse power in the “Global South,” Conor Fiddler writes for International Policy Digest. Chinese scholar Nadège Rolland defines discourse power as “the ability to voice ideas, concepts, propositions, and claims that are ‘respected and recognized by others’ and, by doing so, to generate the power needed to ‘change the thoughts and behaviors of others in a nonviolent and noncoercive way,” he adds.

China’s political warfare is little understood as its matrix is immensely complex and highly deceptive by design, but an integral part of China’s Belt & Road strategy involves the countering and shaping of ideas, says the American Bar Association (ABA).

China’s political warfare is little understood as its matrix is immensely complex and highly deceptive by design, but an integral part of China’s Belt & Road strategy involves the countering and shaping of ideas, says the American Bar Association (ABA).

The sophisticated manipulation of information is utilized to entice membership in the BRI, “sell” projects to the Host country, and engender geopolitical support for China throughout the international community. A forthcoming session of ABA’s BRI program* is aimed at developing better understanding of the nature and extent of China’s influence campaigns (often called “political warfare”), which are leveled at not only the U.S. but also those countries Beijing has now persuaded to join the BRI. This is an especially important challenge for the legal and business communities, as a key weapon in the Political Warfare arsenal is “Lawfare” which being used is to upend the rule of law and concept of human rights as we understand it today.

Controversy over BRI is fueled by a lack of transparency that makes it difficult to get reliable information on the financing involved in the initiative, as well as the specific projects and their terms, says Brookings expert David Dollar, who cites a growing number of academic efforts to collect and analyze data on BRI, with a consistent set of findings. Developing countries have various funding sources already, he adds:

Controversy over BRI is fueled by a lack of transparency that makes it difficult to get reliable information on the financing involved in the initiative, as well as the specific projects and their terms, says Brookings expert David Dollar, who cites a growing number of academic efforts to collect and analyze data on BRI, with a consistent set of findings. Developing countries have various funding sources already, he adds:

They prefer to use Chinese financing for big projects in transport and power for specific reasons. Private funding is too expensive and short-term (usually max five years). Western donors and their multilateral banks give grants or lend on extraordinarily generous terms. But these traditional donors prefer to finance social services, administration, democracy-promotion – they have gotten out of hard infrastructure almost completely.

Nail in the coffin?

In June this year, the Chinese Foreign Ministry announced that about 20 percent of the projects under its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) had been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, notes analyst Lee Ying Hui. But even before COVID-19, the BRI was facing increasing criticism in host countries for its lack of transparency, displacement of local communities, adverse environmental impacts and fears of “debt-trap diplomacy,” among many other issues, he writes for The Diplomat. With the pandemic inevitably delaying many of BRI’s physical infrastructure projects, will COVID-19 be a nail in the coffin or a turning point for the BRI?

CNAS

The Belt and Road Initiative is an excellent example of how Beijing weaves economic, political/diplomatic, and technological elements together to achieve its strategic aims, according to Heritage analysts Walter Lohman and Riley Walters. These efforts are facilitated by the reality that China is not a market economy: Many of them are undertaken by state-owned enterprises that are insulated from the full impact of their business decisions, they wrote in a recent analysis. The Chinese Communist Party hopes that economic investments of this sort will generate not only economic, but also strategic political, and perhaps even military benefits.

Chinese authorities employ the BRI primarily as a “multidimensional strategy that advances China’s notion of itself as an uncontested leading power,” argues Rolland, a senior fellow for political and security affairs at the National Bureau of Asian Research.

Chinese authorities employ the BRI primarily as a “multidimensional strategy that advances China’s notion of itself as an uncontested leading power,” argues Rolland, a senior fellow for political and security affairs at the National Bureau of Asian Research.

In an episode of the Power 3.0 podcast, she traces The Evolution of China’s Belt and Road Initiative since its launch in 2013, with a particular emphasis on understanding Beijing’s priorities and the underlying strategic objectives accompanying its marketed emphasis on overseas infrastructure development. Christopher Walker, National Endowment for Democracy vice president for studies and analysis, and Shanthi Kalathil, senior director of the NED’s International Forum for Democratic Studies, cohost the conversation.

*November 18, 2020: “The Battle of Ideas-The Role of the BRI in China’s Political Warfare” 1:00 PM – 2:30 PM EDT

The U.S. is ramping up efforts to secure minerals critical to modern technology but whose supply is dominated by China—a stranglehold that miners warn could take years to break https://t.co/DVn46pDmuJ via @WSJ

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 5, 2020