Credit: Princeton UP

What is the danger to an autocratic regime if it loses control over civil society?

In the latest confirmation of the Russian authorities’ disregard for a vibrant and independent civil society, the European Union condemned recent decisions taken by the Prosecutor General’s Office to list several non-governmental organizations, including the Prague-based Společnost Svobody Informace (Freedom of Information Society) as “undesirable organizations.”

But the EU should go further an develop a multilayered strategy to engage and support civil society, argues Maria Domańska, a senior fellow at the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW) in Warsaw, Poland. Not least in case a narrow window of opportunity for democratic change opens in Russia, she writes for Carnegie Europe.

Putin’s Lasting State?

In an authoritarian state, civil society is often perceived as an adversary rather than as a partner as it is in a democratic state. Controlling internal and external challenges from civil society has been a primary concern of Russia’s rulers over the centuries, notes Robert E. Berls, NTI’s Senior Advisor for Russia and Eurasia.

Wikipedia

“The character of the Russian state has been central in shaping Russian strategic thinking,” Kremlin ideologue Vladislav Surkov (right), framer of the term “sovereign democracy,” wrote in an important article, ‘Putin’s Lasting State‘. “It has never been conceived as an emanation of society, instituted to protect the rights of citizens, temper the consequences of conflicts among them and advance the public weal,” adding, with characteristic cynicism:

The multilayered political institutions which Russia had adopted from the West are sometimes seen as partly ritualistic and established for the sake of looking “like everyone else,” so that the peculiarities of our political culture wouldn’t draw too much attention from our neighbors, didn’t irritate or frighten them. They are like a Sunday suit, put on when visiting others, while at home we dress as we do at home.

Over the past week, Russia’s political parties have been submitting nomination papers for their candidates in September’s parliamentary election. In some cases, gathering the documents has proved more difficult than in others, notes Free Russia’s Vladimir Kara-Murza. One such case involves Yabloko, the last (genuine) opposition party that still retains ballot access — a relic of Russia’s brief stint with democracy in the 1990s, he writes for the Post:

Over the past week, Russia’s political parties have been submitting nomination papers for their candidates in September’s parliamentary election. In some cases, gathering the documents has proved more difficult than in others, notes Free Russia’s Vladimir Kara-Murza. One such case involves Yabloko, the last (genuine) opposition party that still retains ballot access — a relic of Russia’s brief stint with democracy in the 1990s, he writes for the Post:

Its list of candidates for the State Duma, the lower house of parliament, includes Andrei Pivovarov, an opposition activist held in pretrial detention and facing up to six years in prison on a charge of belonging to an “undesirable organization” (in his case, the now-defunct Open Russia, founded by exiled Putin critic Mikhail Khodorkovsky). Arrested in May onboard a Polish passenger plane (a tactic echoing Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko), Pivovarov is among the nearly 400 individuals in Russia recognized by human rights groups as political prisoners — and the only one to run in this year’s election.

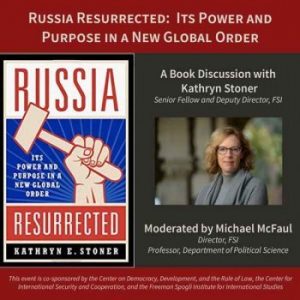

Credit: Stanford CREEES

Taken together, two recently published books – Kathryn E. Stoner’s Russia Resurrected: Its Power and Purpose in a New Global Order and Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin’s Russia by Timothy Frye – are a welcome contribution to scholarship and policy, notes Celeste A. Wallander, president and CEO of the U.S. Russia Foundation.

Russia is explicable, they both assert, and not, as Winston Churchill quipped, “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma,” she writes for the Journal of Democracy. An understanding of both Russia’s strengths and its weaknesses should enable democracies to develop policies to manage its disruptive and destructive actions, while leaving room for cooperation where interests align. Armed with knowledge of the idiosyncrasies of Putin—the weak strongman—and the personalist autocracy that he heads, free governments can counter Russia’s asymmetric influence operations. RTWT

With the weakening of the Kremlin’s ideological message and the state’s growing reliance on repressive measures, it is becoming increasingly apparent that the state is losing control over the social agenda and is no longer able to respond to the needs of society, Berls adds. As Tatyana Stanovaya of Carnegie Moscow Center states, “In its twentieth year, the Putin system is closing in on itself and self-isolating from society.”

In Moscow, according to the independent Levada polling center, Putin’s party is at 15 percent, Kara-Murza adds. Yet the Kremlin is signaling plans to keep its two-thirds majority in the next parliament — a mathematically impossible feat given the poll numbers. Perhaps the only remaining way to make this happen would be outright, old-school fraud. The last time the Kremlin resorted to this, in 2011, Russia saw the largest street protests of Putin’s rule. RTWT

“This aging and decaying political system is rejected by society,” Pivovarov wrote in a letter from jail last week. “The only thing supporters of change are getting from the authorities are [police] batons and criminal cases — but this strategy is unworkable even in the medium term. If society’s demands are not met, protests will find unexpected avenues. … I am certain that this cannot continue for long.”

Lyudmila Alekseyeva (right), a founding member of the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group and recipient of the NED’s 2004 Democracy Award, blamed society for its aloofness from political life that has facilitated the authorities arbitrary rule, Berls notes:

(right), a founding member of the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group and recipient of the NED’s 2004 Democracy Award, blamed society for its aloofness from political life that has facilitated the authorities arbitrary rule, Berls notes:

Fortunately, there are bold and courageous individuals brave enough to carry on the civic activism of Alekseyeva and her contemporaries. These individuals are today’s leaders at the forefront of civil society who are willing to risk their private lives and personal freedom for a better life for the Russian people. Ironically, the political activism being waged by a small cadre of civil society leaders is helping the non-activists, the apolitical masses to begin, as Yevgeny Gontmakher of the Institute of Contemporary Development points out, to “slowly but surely, to rise up off [their] knees…and recognize [themselves] no longer as part of the faceless mass of people but as individual[s] with dignity and personal interests.”

And yet, Berls adds, as analyst Mark Galeotti has observed: “…. even Russians are aware of the impermanence of power and are not willing to indulge any leader forever.” Read the rest.