Russia isn’t the only authoritarian state to exploit new technologies for the purpose of undermining democracy and advancing illiberal values, analysts suggest.

Russia isn’t the only authoritarian state to exploit new technologies for the purpose of undermining democracy and advancing illiberal values, analysts suggest.

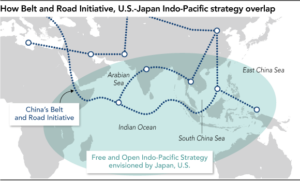

China’s planned development of a “new digital Silk Road” threatens to enhance the regime’s political leverage and expand what a National Endowment for Democracy report describes as Beijing’s ’sharp power’, according to former State Department official Richard Fontaine and former Department of Defense official Daniel Kliman.

“China’s digital blueprint seeks to promote information technology connectivity across the Indian Ocean rim and Eurasia through new fiber optic lines, undersea cables, cloud computing capacity, and even artificial intelligence research centers. If realized, this ambitious vision will serve to export elements of Beijing’s surveillance regime,” they write for Foreign Policy.

Democracies need to respond to ensure that “the illiberal values China is exporting under the guise of the Belt and Road Initiative do not take root across the globe,” by bolstering international support for democracy, civil society, and rule of law.

Democracies need to respond to ensure that “the illiberal values China is exporting under the guise of the Belt and Road Initiative do not take root across the globe,” by bolstering international support for democracy, civil society, and rule of law.

“Transparency, domestic checks and balances, and a free press can function as powerful impediments to the sort of corrupt backroom deals that leave China with enduring financial leverage and receiving governments with a long-term debt hangover,” note Fontaine and Kliman, adding that even modest efforts to train investigative journalists or to strengthen the capacity of civil society groups would help counter China.

“Undertaken in concert with U.S. allies and partners, these kinds of moves will not demand massive new resources. But absent steps like them, Belt and Road-fueled illiberalism will spread across the globe unchecked,” they conclude.

“Undertaken in concert with U.S. allies and partners, these kinds of moves will not demand massive new resources. But absent steps like them, Belt and Road-fueled illiberalism will spread across the globe unchecked,” they conclude.

China’s foreign influence operations and the challenge of reducing Russian soft power are evidence that democracies are in strategic competition with revisionist authoritarian powers, observers suggest.

What is most striking about both the new National Defense Strategy (NDS) and the new National Security Strategy (NSS) is the dominant theme of strategic competition with Russia and China evident in each. Iran, North Korea, and transnational terrorism are described and assessed as threats, but they are clearly seen as less important than—certainly not as existential as—the challenges posed by Russia and China, notes Dr. John R. Deni.

There may be good reasons why the new NSS and NDS do not provide greater insights into what policies may underpin a more competitive approach toward Russia. But before outlining those policy elements, some important caveats are necessary, he writes for the Strategic Studies Institute’s Parameters:

There may be good reasons why the new NSS and NDS do not provide greater insights into what policies may underpin a more competitive approach toward Russia. But before outlining those policy elements, some important caveats are necessary, he writes for the Strategic Studies Institute’s Parameters:

- First, it’s vital to recognize that a competitive strategy must employ all elements of American power, not simply the military, which it seems is increasingly the tool of first resort on the part of the White House and Congress.

- Second, in designing a set of competitive policies, it is necessary to remain focused on the objective. That is, in crafting and choosing specific policies, decision-makers must ask themselves whether a given policy will ultimately reduce Russia’s power—broadly defined—to threaten the United States and its allies or hold Western interests at risk. Competition for its own sake is pointless, and a collapsed Russia is in no state’s interests. However, a less powerful Russia may be less likely to invade a neighbor, prop up a weapon of mass destruction (WMD)-wielding dictatorship, stage massive no-notice military exercises, use energy as a weapon, or sabotage the critical infrastructure of the United States or an ally.

Third, a competitive set of policies does not necessarily amount to containment, isolation, or confrontation. Pursuing any of these would only fulfill Russia’s false narrative, allowing it to continue demonizing the West. Of course, Moscow is likely to attempt to do so in any case, but by avoiding direct containment, isolation, and confrontation, the United States can more effectively avoid playing into the Kremlin’s hands, while also keeping fiscal and other costs manageable.

Third, a competitive set of policies does not necessarily amount to containment, isolation, or confrontation. Pursuing any of these would only fulfill Russia’s false narrative, allowing it to continue demonizing the West. Of course, Moscow is likely to attempt to do so in any case, but by avoiding direct containment, isolation, and confrontation, the United States can more effectively avoid playing into the Kremlin’s hands, while also keeping fiscal and other costs manageable.

Reducing Russian soft power

With these important factors in mind, what might a more competitive set of policies look like? Deni asks:

- For example, in terms of diplomatic efforts, the United States should end bilateral summits and state visits with Russia. Russia’s President Putin clearly savors opportunities to appear on the world stage next to American presidents. … Moreover, most engagement with Russian counterparts should occur at the many levels below that of head of state. Ending high-visibility summits and state visits would help to diminish Russia’s soft power—domestically and internationally—without unduly affecting the ability of governments to talk with

each other.

each other. - Additionally, the United States should seek to keep Russia permanently out of the Group of Seven advanced industrial economies. Permanently excluding Russia from the group would have the effect of further reducing Russian soft power, both domestically and internationally….

- Finally, when considering how to use posture and force structure to compete with Russia, U.S. military decision-makers need to think beyond institutional biases. …An American armored brigade stationed in Poland has great deterrent and operational value vis-à-vis an overt Russian military incursion in Northeastern Europe, but it has very little utility against far more likely—and, to date, more prevalent—Russian efforts to conduct so-called gray zone activities in the electromagnetic spectrum, in the cyber realm, in the information space, and elsewhere. RTWT