Georgia’s status as a post-Soviet democratic leader is under challenge, according to analysts Denis Corboy, William Courtney, Kenneth Yalowitz. A flawed presidential election, use of force against protesters, and political manipulations by the secretive billionaire who heads the ruling Georgian Dream Party have strained public confidence and brought mounting public protests. Domestic calm may hinge on improving political dialogue and conducting free and fair parliamentary elections in fall, 2020.

Independent Georgia has made substantial democratic progress, aided by multiparty elections, robust civil society organizations, and media freedoms. In 2003 the Rose Revolution—a peaceful uprising against political stagnation—accelerated democratic momentum. Now Georgians may again be tiring of poor governance and lack of transparency. A National Democratic Institute poll last July found that 60 percent of respondents evaluate the performance of the current government as “bad,” they write for The National Interest:

Democratic momentum persisted until last year’s presidential election. National Democratic Institute observers cited aggressive, personalized, and unprecedented attacks by senior state officials against the country’s most respected civil society organizations, “abuse of administrative resources,” and the lack of a level playing field, even though “fundamental freedoms of expression, assembly, and association” were largely respected.

Georgian democracy ‘crumbling’?

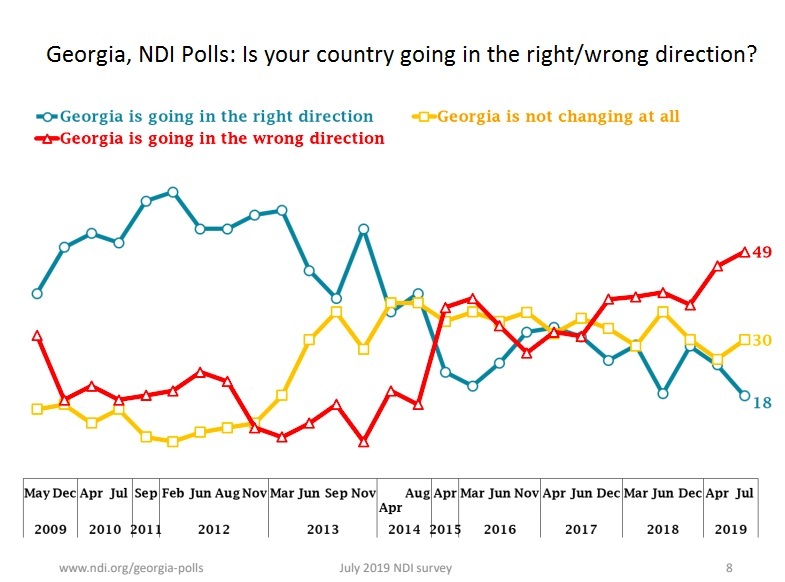

Trapped by oligarchic interests, the country remains politically divided, according to Professor Kornely Kakachia, director of the Georgian Institute of Politics, and Dr Bidzina Lebanidze, a senior fellow at the institute. Perceptions of the country’s direction have hit their lowest levels since 2010. According to a recent public opinion poll by the International Republican Institute (IRI), 68 percent of respondents say the country is moving in the wrong direction. With Georgian democracy crumbling, the only way to stabilize the country is to support a sustainable multi-party political system and to institutionalize consensus-based democratic processes.

Trapped by oligarchic interests, the country remains politically divided, according to Professor Kornely Kakachia, director of the Georgian Institute of Politics, and Dr Bidzina Lebanidze, a senior fellow at the institute. Perceptions of the country’s direction have hit their lowest levels since 2010. According to a recent public opinion poll by the International Republican Institute (IRI), 68 percent of respondents say the country is moving in the wrong direction. With Georgian democracy crumbling, the only way to stabilize the country is to support a sustainable multi-party political system and to institutionalize consensus-based democratic processes.

Georgia’s democratic success matters for the EU for three reasons, Kakachia and Lebanidze contend:

Georgia’s democratic success matters for the EU for three reasons, Kakachia and Lebanidze contend:

- First, Georgia is considered one of the few success stories of the otherwise moderately successful European Neighborhood Policy and Eastern Partnership initiative, the two key instruments of EU external governance in the Eastern neighborhood. With Moldova and Ukraine—the other two associated states with decent democratic credentials—not in good shape , Georgia’s slide toward authoritarian democracy would undermine the last remaining poster child of the EU’s soft power in the region.

- Second, the possible autocratic consolidation also undermines the EU’s key goal in its neighborhood: political stability and peaceful development. Unlike some of the other neighborhood states, the societies in countries like Georgia and Ukraine have grown pluralist by default and, therefore, any attempt at imposing autocratic governance produces more political turmoil and a public backlash.

- Third, if the backsliding continues, Georgian democracy will more likely drift toward illiberal actors such as Russia and China. This is not the aspirations of Georgian society, they write for the Carnegie Endowment.

Georgia’s civil society has long been a good example of an engaged and informed citizenry, with the protests in June 2019 having largely secured a promise from the government that it would seek a change in the election system from a mixed system to a fully proportional one, notes analyst Mariam Uberi. The dropping of those proposed constitutional amendments in November 2019, however, triggered the biggest anti-government protest in years, she writes for the London-based Foreign Policy Centre:

On a political level, the backtracking on promised constitutional change is largely seen as fear by the ruling party of losing power. The authorities’ response to that fear seems to be the flagrant ignorance of the rule of law and the safeguards on freedom of expression and the right to peaceful assembly as they attempt to flatten the increased mistrust and heightened tensions between the ruling party, opposition and civil society.

An orchestrated campaign against U.S. democracy assistance NGOs “is being run out of the Kremlin,” says Dr. Daniel Twining, IRI President. “When we hear foreign politicians, foreign governments, attacking American NGO’s it is usually in cases like Russia and China, where there is no political freedom, where there is no democratic practice. So It is surprising to hear it in a democracy,” he said in an interview with the Voice of America, responding to accusations by Georgian Dream leader, Bidzina Ivanishvili.

The National Democratic Institute (NDI) and the International Republican Institute (IRI) – core institutes of the National Endowment for Democracy – work closely with partners across the political spectrum, including the ruling Georgian Dream party and opposition parties, said Representative Eliot L. Engel, Chairman of the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee. They do not choose sides or support particular political outcomes.