Jordan Kyle & Limor Gultchin, Populists in Power Around the World, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

There is a specter haunting not just Europe, but the whole globe, quaking the boots of established political parties, legacy media outlets, and transnational institutions of government and civil society. Arguably five times as many people live under populist governments at the end of 2019 than at the end of 2009, notes analyst Matt Welch.

This creeping dread is gathered under the catch-all label of “populism.” Cosmopolitan elites are on alert for its “dangerous rise.” Unelected bureaucracies are being hollowed out in its wake, including this week at the World Trade Organization. It certainly feels like one of the biggest global upheavals of this waning decade, with each new week coughing up headlines like “Inauguration Marks Return of Peronism.” But are there measurable facts to back up this feeling? he asks in Reason magazine:

The short answer is yes: But the longer answer requires some more precise definitions. Start with a working model of the ism under question.

Jordan Kyle and Limor Gultchin, in Populists in Power Around the World, a very useful survey from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, synthesize the political science literature into two fundamental assertions underlying every governing populist movement: 1) “A country’s ‘true people’ are locked into conflict with outsiders, including establishment elites,” and 2) “Nothing should constrain the will of the true people.” Leaders then govern in an atmosphere of near-constant existential urgency. From there, the authors differentiate three main populist variants:

Jordan Kyle and Limor Gultchin, in Populists in Power Around the World, a very useful survey from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, synthesize the political science literature into two fundamental assertions underlying every governing populist movement: 1) “A country’s ‘true people’ are locked into conflict with outsiders, including establishment elites,” and 2) “Nothing should constrain the will of the true people.” Leaders then govern in an atmosphere of near-constant existential urgency. From there, the authors differentiate three main populist variants:

1) Socio-economic populism (think: Venezuela), which claims that “the true people are honest, hard-working members of the working class,” fighting against “big business, capital owners and actors perceived as propping up an international capitalist system.”

2) Anti-establishment populism (think: Silvio Berlusconi’s Italy), which “paints the true people as hard-working victims of a state run by special interests and outsiders as political elites.”

3) Cultural populism, which claims that “the true people are the native members of the nation-state” battling over national sovereignty and cultural identity with the likes of “immigrants, criminals, ethnic and religious minorities, and cosmopolitan elites.”

3) Cultural populism, which claims that “the true people are the native members of the nation-state” battling over national sovereignty and cultural identity with the likes of “immigrants, criminals, ethnic and religious minorities, and cosmopolitan elites.”

But populists lack the skills, temperament and support to construct a new world order, other analysts suggest.

Enemies of democracy have, of course, always manipulated feelings. Yet we believe that there’s a key lesson from 1989 that liberalism can learn, say Karolina Wigura, a political editor of the Polish weekly Kultural Liberalna, and Jarosław Kuisz, editor-in-chief of the Polish weekly Kultura Liberalna – both fellows at Berlin’s Institute of Advanced Studies.

We need a passionate defence of liberal democracy and the liberal order. We also need to embrace the feeling of loss and translate it into something positive and enriching, into a feeling about political community, they write for the Guardian:

How could this be done? The collective sense of loss we have been describing is akin to the grief that follows the death of a loved one. In bereavement our first reaction is to look back, to dwell on the loss. Reactionary populism’s concentration on the negative aspects of transformation might be compared with bereavement. As humans we know that after bereavement comes the recovery phase. And this means looking to the future and building networks of friends. It requires courage, hope and compassion – especially for those who think so differently that they vote for populists.

“This is what the liberalism of the future could mean. It could retell the story of 1989, while doing justice to this great and complex moment,” they add. “Central and eastern Europe still has an important message for the world. It is the knowledge that the greatest successes of liberal democracy, including 1989, were enabled by passionate hope.”

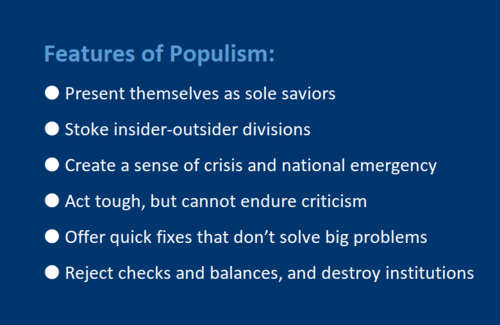

Populist regimes exhibit four defining features, as Takis S. Pappas contends in his April 2019 article on “Populists in Power,” in the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy), analyst Naomi Chazan observes:

Populist regimes exhibit four defining features, as Takis S. Pappas contends in his April 2019 article on “Populists in Power,” in the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy), analyst Naomi Chazan observes:

- The first is charismatic leadership. Non-liberal democracies with strong populist overtones are closely associated with attractive, articulate, mobilizing leaders who have the capacity to control their political movements (often by eradicating liberal voices from within their parties) and building up broad popular support for themselves and their goals….

- The second characteristic of non-liberal democracies is polarization. Studiously cultivating divisions between different groups and perspectives is not, in these instances, merely a matter of ideological differences of opinion. It is seen as a strategy that defines the people (in contrast to the previously dominant elites) and links them inextricably to the leader….

- The third element of non-liberal democracy focuses on the takeover of the state apparatus. It has come to mean the systematic dispensation of jobs to administration loyalists…. It also involves the undercutting of what remains of the institutional checks and balances in the system (most notably attacks on the independence of the judiciary, the freedom of the media, civil society organizations and critical elements of the educational system). Inevitably, this process also entails efforts to tamper with the constitutional foundations of the state….

- From here, it is but a short step to the fourth feature of non-liberal democratic governments: the widespread dispersion of state resources as patronage to supporters…..

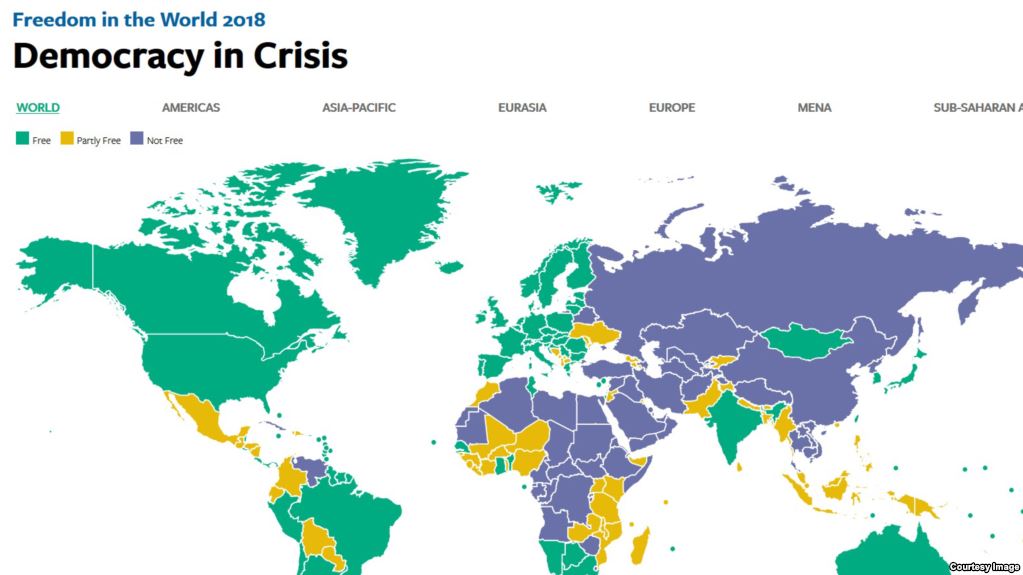

Freedom House

Those who compile global indices of democratic health are in a glum mood these days, Reason’s Welch adds:

- Freedom House’s annual “Freedom in the World” survey for 2019 was headlined “Democracy in Retreat,” lamenting a “13th consecutive year of decline in global freedom.” (Surely, we will soon read about a 14th.) Conclusion: “The reversal has spanned a variety of countries in every region, from long-standing democracies like the United States to consolidated authoritarian regimes like China and Russia. The overall losses are still shallow compared with the gains of the late 20th century, but the pattern is consistent and ominous.”

- A newer index introduced by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project at the University of Gothenburg finds that “the number of liberal democracies has declined from 44 in 2008 to 39 in 2018,” and that “almost one-third of the world’s population lives in countries undergoing autocratization, surging from 415 million in 2016 to 2.3 billion in 2018.” These include India, Brazil, and the United States.