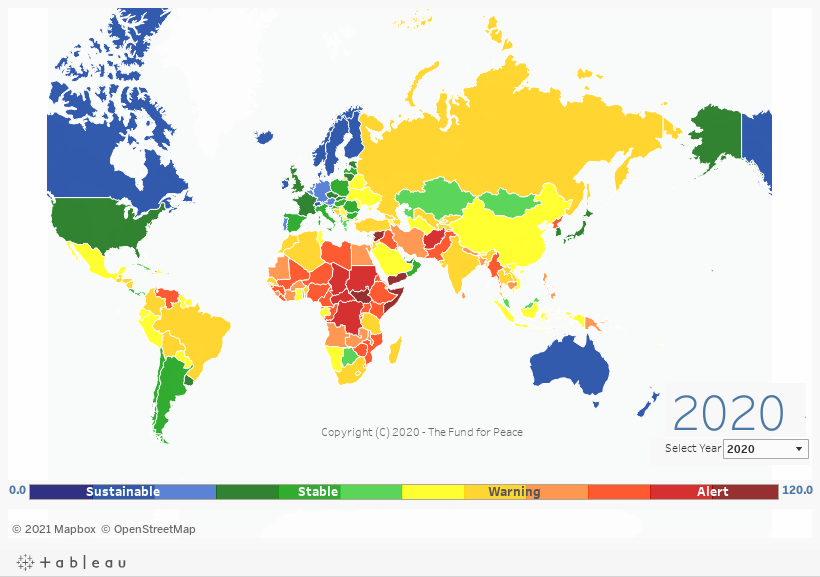

Fragile States Index

The Summit for Democracy’s Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal dedicates $424.4 million to defend and strengthen democracy. Nowhere is this more pressing than in the 57 countries considered fragile by the OECD, which are characterized by breakdowns in state legitimacy and public service delivery, notes Lauren Mooney, the Senior Specialist for Conflict Prevention and Stabilization at the International Republican Institute (IRI), a core partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

But complex challenges impede the provision of effective support to places riven by or trending toward conflict. Experience and research show that the United States must account for three critical issues as it tries to advance its democracy agenda in places wracked by conflict and fragility, she writes for Just Security:

- First, policymakers and practitioners should carefully consider the interaction between state and non-state governance institutions—and which have legitimacy in the eyes of the population. Democracy and governance assistance often relies on Western models of political institutions and groups. Yet formal political institutions are often predatory or widely perceived as illegitimate in fragile settings. ….

Second, the U.S. government should integrate anti-corruption practices across foreign assistance in fragile contexts. The U.S. government has rightly established anti-corruption as a national security priority. …. The top 10 most corrupt countries in the world also rank high on the Fragile States Index (above) – Somalia, South Sudan, and Syria among them. … [Anti-corruption] programs must not only assess vulnerabilities to corruption and promote transparency, but also incorporate safeguards against corruption, identify trusted, sometimes nontraditional partners, and evaluate the footprint of an intervention to identify its impact on corruption—including whether it reinforces corrupt incentives.

Second, the U.S. government should integrate anti-corruption practices across foreign assistance in fragile contexts. The U.S. government has rightly established anti-corruption as a national security priority. …. The top 10 most corrupt countries in the world also rank high on the Fragile States Index (above) – Somalia, South Sudan, and Syria among them. … [Anti-corruption] programs must not only assess vulnerabilities to corruption and promote transparency, but also incorporate safeguards against corruption, identify trusted, sometimes nontraditional partners, and evaluate the footprint of an intervention to identify its impact on corruption—including whether it reinforces corrupt incentives.- Third, policymakers and practitioners should take a politically informed approach in order to mitigate against potential backlash from interventions. …. For example, participants in countering violent extremism (CVE) projects or research may be stigmatized because their involvement may be interpreted to imply they are vulnerable to violent extremism….Similarly, efforts to promote social cohesion can easily backfire, especially if assistance is provided to one group and excludes another. If such initiatives are not implemented carefully, they can increase mistrust within communal groups, reinforce prejudice, and introduce new divisions. RTWT

In many so-called fragile states, government institutions are weak, according to Saferworld’s Jason S. Calder and Lauren Van Metre, a senior advisor at the National Democratic Institute (NDI). However, in A Savage Order: How the World’s Deadliest Countries Can Forge a Path to Security, author Rachel Kleinfeld [a new board member of the National Endowment for Democracy – NED] cautions that we must be careful regarding our assumptions about state fragility.

In many so-called fragile states, government institutions are weak, according to Saferworld’s Jason S. Calder and Lauren Van Metre, a senior advisor at the National Democratic Institute (NDI). However, in A Savage Order: How the World’s Deadliest Countries Can Forge a Path to Security, author Rachel Kleinfeld [a new board member of the National Endowment for Democracy – NED] cautions that we must be careful regarding our assumptions about state fragility.

Some countries do suffer from weak institutions despite efforts to strengthen them. In other countries, however, elites intentionally keep state institutions weak so they can maintain their political and economic privileges. Kleinfeld discusses the impact of “intentional fragility” on security forces and the exercise of violence, but it extends to democratic institutions as well, they write for Foreign Policy.