Pandemic geopolitics are intensifying investments in pro-democracy civic capacities and democracies’ societal resilience, according to a new report from the Carnegie Endowment. Developments are beginning to condition many states’ domestic politics, pushing and pulling global civic activism in contrasting directions, say the authors of Civil Society and the Global Pandemic: Building Back Different?

The fundamentals of liberal democracy – “a mixture of civic norms, guaranteed rights, market freedom, social spending and judicious regulation” – are essentially sound, argues Harvard’s Steven Pinker. But insofar as they’re wanting, the balance of these elements should be cautiously tweaked and twiddled through experimentation and empirical feedback, he tells the Guardian.

“Whatever happened to good old liberalism?” asks Pinker, the author of several books, including Enlightenment Now and Rationality, which inspired a current BBC series. “Who’s going to actually step in and defend the idea that incremental improvements fed by knowledge, fed by expanding equality, fed by liberal democracy, are a good thing? Where are the demonstrations, where are the people pumping their fists for liberal democracy? Who’s going to actually say something good about it?”

“Whatever happened to good old liberalism?” asks Pinker, the author of several books, including Enlightenment Now and Rationality, which inspired a current BBC series. “Who’s going to actually step in and defend the idea that incremental improvements fed by knowledge, fed by expanding equality, fed by liberal democracy, are a good thing? Where are the demonstrations, where are the people pumping their fists for liberal democracy? Who’s going to actually say something good about it?”

China presents a threat to the liberal global order, but the bigger danger lies in the discrediting of democracy. It remains hard to see how the world can work without liberal democracy and a rules-based international system, but the West is the author of its own weakness, writes FT analyst Philip Stephens.

In terms of discrediting democracy, a foreign policy failure like Iraq or Afghanistan “pales into insignificance against the damage inflicted by the 2008 global financial crash. Historians will record the crash as a momentous geopolitical as much as an economic event — the moment western democracies suffered a potentially lethal blow,” he asserts:

The excesses of the financial services industry and the decision of governments to heap the costs of the crisis on to the working and lower middle classes have struck at the very heart of democratic legitimacy. …Public faith in democracy — in the rule of law and the institutions of the state — rests on a perception that the system at least nods towards fairness. There have been reforms to that end since the crash, but little to suggest they are enough.

The pandemic has highlighted longstanding shortcomings and challenges facing Latin America, says a new report from International IDEA. But now may be the most propitious moment for democratic renewal in decades due to the electoral supercycle that Latin America is experiencing from late 2020 until 2024, a period in which all presidential positions in the region are up for re-election, together with numerous legislative and subnational authorities. It is a unique opportunity that the region cannot afford to miss.

The pandemic has highlighted longstanding shortcomings and challenges facing Latin America, says a new report from International IDEA. But now may be the most propitious moment for democratic renewal in decades due to the electoral supercycle that Latin America is experiencing from late 2020 until 2024, a period in which all presidential positions in the region are up for re-election, together with numerous legislative and subnational authorities. It is a unique opportunity that the region cannot afford to miss.

If they are to generate resilience, representative democracies everywhere need to rebuild broad solidarities that once undergirded prosperity and stable politics, according to Yale University’s Frances McCall Rosenbluth and Brown University’s Margaret Weir, editors of Who Gets What? The New Politics of Insecurity, part of the SSRC Anxieties of Democracy series.

Although rates of inequality in the United States have soared far above those in Europe, a troubling sense of insecurity pervades European democracies as well, they write for the LSE’s EUROPP blog:

As confidence erodes in the capacity of representative government and political parties to alleviate this new insecurity, the field has opened to a new kind of politics. Politicians who openly embrace racism, nationalism, and unilateral executive action now present themselves as the alternative to the failures of liberal representative democracy and global connection.

Intermediary organizations like labor unions and churches are vital elements of a robust democratic culture, not least in countering polarization, a National Endowment for Democracy (NED) forum heard last week. They provide a venue or political space in which citizens encounter those with a different political or ideological commitment, fostering tolerance and pluralism, especially at a time of growing residential segregation along political and ethnic lines, at least in the United States.

Which is why the role of labor unions, a key bulwark of postwar democracy in Europe and North America, is a curious omission from Jan Werner Müller’s Democracy Rules: Liberty, Equality, and Uncertainty, notes Harvard University’s Daniel Ziblatt. Labor unions before and after WWII were essential preconditions of both expanding and stabilizing democracy, and their role in political education was critical, he writes for Democracy.

Which is why the role of labor unions, a key bulwark of postwar democracy in Europe and North America, is a curious omission from Jan Werner Müller’s Democracy Rules: Liberty, Equality, and Uncertainty, notes Harvard University’s Daniel Ziblatt. Labor unions before and after WWII were essential preconditions of both expanding and stabilizing democracy, and their role in political education was critical, he writes for Democracy.

Proving democracy works

Given the threats posed by economic inequality to democracy, labor unions’ role in reducing wage disparities made democracy more stable. And finally, the linkage between unions and parties of the center-left in Europe and North America were critical in forging a broad coalition that pushed for political inclusion of African Americans in the United States and more inclusive democracies in Western Europe, adds Ziblatt, director of the Transformations of Democracy research unit at the WZB Social Science Center Berlin (Germany), the co-author, with Steve Levitsky, of How Democracies Die, and a contributor to the NED’s Journal of Democracy.

And as for churches……..

Robert Wuthnow, a professor emeritus of sociology at Princeton, explains in “Why Religion Is Good for American Democracy,” that churches play a role of “agonistic pluralism” – in short, beneficial conflict, the Wall Street Journal’s Barton Swaim observes.

Robert Wuthnow, a professor emeritus of sociology at Princeton, explains in “Why Religion Is Good for American Democracy,” that churches play a role of “agonistic pluralism” – in short, beneficial conflict, the Wall Street Journal’s Barton Swaim observes.

“Democracy does not necessitate everyone believing the same thing,” Wuthnow writes. “Democracy is strengthened more by citizens acknowledging and accepting diversity—and willingly contending for different beliefs.”

Can we predict autocratic trajectories before they become irreversible?

This week saw the launch of a new Democratic Resilience Index, drawing on state-of-the-art social science concerning democratic transitions, democratic backsliding and ‘autocratization‘.

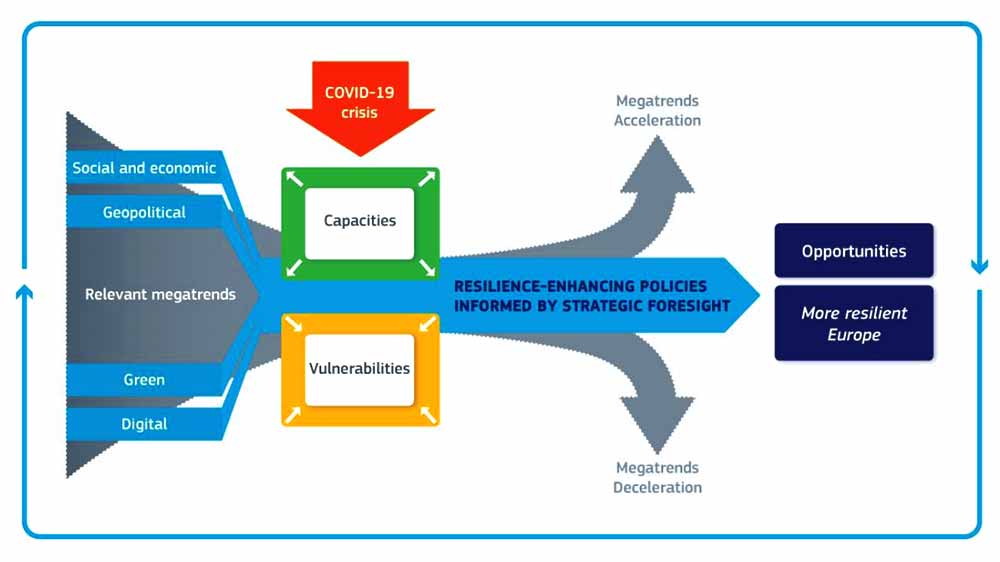

The first quantitative instrument specifically designed to measure democratic resilience was developed for the European Commission and The German Marshall Fund of the United States, drawing on pilot research in Romania, Hungary and Moldova, the Global Focus Center reports.

The index proposes a new approach and methodology, grounded in academic literature and institutional practice, to identify triggers of resilience in emerging and consolidated democracies, through a multi-dimensional matrix including Politics & Governance, Media & Civil Society, Economy & Foreign Affairs. It identifies institutional/ structural resilience drivers in each country, elite agency, key buffers against democratic backsliding, potential crisis triggers, and provides recommendations for policy interventions to build more resilient democracies.

Credit: European Commission

Analysts Hager Ali and Ameni Mehrez insist that recent developments in Tunisia are more a testament to democratic resilience than failure.

To make democracies more resilient to domestic and foreign challenges, the Biden administration can do four things, according to Brookings and IRI analyst Patrick Quirk:

- First, the U.S. should make protecting and supporting democracy abroad a central U.S. interest that directly influences policy and strategy for other functional issues — from combatting global fragility and forging regional trade policy to collaborating with allies to devise a more open and transparent digital domain…..

- Second, the administration should continue the U.S. focus on strengthening the core institutions, practices, and norms that enable a society to respond and adapt to the spectrum of domestic and foreign threats. Strong democratic institutions with established accountability mechanisms are the most formidable line of defense against threats both domestic and foreign, whether from elite attempts to erode civic freedoms or foreign countries exerting malign influence…..

- Third, the U.S. should dedicate greater effort to helping governments and civil society better detect, expose, and counter foreign authoritarian influence, whether from China or Russia. In many vulnerable countries there is limited understanding of the often-covert tactics the CCP or Kremlin employ to coerce, corrupt, and manipulate a range of actors to advance their strategic interests. …

- Finally, the Biden administration must focus on creating and implementing a positive vision of the future of democracy, one that embraces digital technology to advance democratic principles and global cooperation. …

The European Union this week announced five initiatives worth €119.5 million to enhance support to democracy and human rights, specifically:

The European Union this week announced five initiatives worth €119.5 million to enhance support to democracy and human rights, specifically:

- €5 million for the Democracy Support Alliance will foster data collection and analysis, and strengthen cooperation between the EU and its Member States in the area of democracy and human rights.

- The EU will support the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the human rights pillar of the United Nations, with €4.8 million for its 2021 budget.

- Around €100.8 million will be used to support local civil society organisations, democracy activists and human rights defenders in 116 partner countries.

- The €4 million from the EU’s Human Rights Crises Facility will continue to provide rapid and confidential support to civil society organisations in some of the world’s most difficult, dangerous and unpredictable political situations.

- The Global Campus of Human Rights, a unique network of one hundred universities, will receive €4.9 million for the academic year 2021-2022.

Democracy and Resilience was the rubric under which the Community of Democracies convened government official and civil society activists on the fringe of this year’s UN General Assembly (see below).

On September 22, 2021, foreign ministers and high-level officials from democratic states, representatives of civil society and youth gathered at #CoD10Ministerial hosted by FM @BogdanAurescu @MAERomania on the margins of #UNGA

Press release https://t.co/T2i6gsJ7GS pic.twitter.com/JaksR5aUfX

— CoD (@CommunityofDem) September 23, 2021

Former National Endowment for Democracy President Carl Gershman sits down with CEPA President and CEO Alina Polyakova (below) to discuss his 30-year career, the current situation for democracy advocates in Russia, China, and around the world, and what the future holds for the next generation of activists.