Authoritarian regimes such as Russia and China see two main uses for international organizations: protecting their regimes and undermining Western values. That’s why they try to control and then corrupt them as much as possible. The story of the Russian diplomat Vladimir Kuznetsov is a perfect case in point, the Washington Post’s Josh Rogin writes.

“For too long, Western democracies have taken a laissez – faire approach to defending the rules of rules-based institutions, while authoritarian regimes work to shape them to do their bidding,” he adds. “Solving that problem is crucial to winning the grand strategic competition and preserving our security, prosperity and freedom.”

DNI.GOV

Moscow and Beijing “are expanding cooperation with each other and through international bodies to shape global rules and standards to their benefit and present a counterweight to the United States and other Western countries,” said the U.S. intelligence community’s Worldwide Threat Assessment released this week.

Former national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski warned in 1997 that the greatest long-term threat to U.S. interests would be a “grand coalition” of China and Russia, “united not by ideology but by complementary grievances.” This coalition “would be reminiscent in scale and scope of the challenge once posed by the Sino-Soviet bloc, though this time China would likely be the leader and Russia the follower,” note analysts Graham Allison and Dimitri K. Simes.

ECFR

A sound U.S. global strategy would combine greater realism in recognizing the threat of a Beijing-Moscow alliance, and greater imagination in creating a coalition of nations to meet it, they write for the Wall Street Journal.

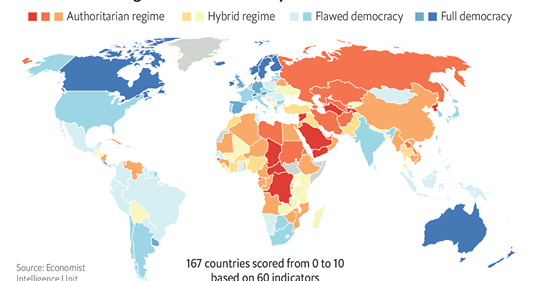

Democracy is making a resurgence, according to the National Democratic Institute’s Adam George, who draws on the recent EIU Democracy Index (above). but there are no grounds for complacency.

Commitment to defending democracy and rule of law in the face of authoritarian resurgence underpins a bipartisan consensus on foreign policy and national security, says a leading expert.

Recently, the Texas National Security Review published two roundtables on the future of conservative and progressive foreign policy, featuring essays by some of the leading figures on both sides of the debate, notes James Goldgeier, professor of international relations at American University.

“Both progressives and conservatives support maintaining America’s democratic alliances in the face of authoritarian challenges from countries like China and Russia,” he writes for War On The Rocks.

“Both progressives and conservatives support maintaining America’s democratic alliances in the face of authoritarian challenges from countries like China and Russia,” he writes for War On The Rocks.

“The greatest point of convergence across these two roundtables is the centrality of democracy and the rule of law,” Goldgeier adds. But….

It is disappointing that the authors do not write more on the specifics about interventions and trade agreements. After all, these are two of the central issues around which any future bipartisan foreign policy would have to be built. For example, for internationalists who support democracy promotion and human rights, what form should those efforts take? It’s easy to argue for more money for the U.S. Agency for International Development (on the progressive side anyway), but where do folks come down on the interventions of the past 25 years?

‘Russia Is a Rogue. China Is a Peer.’

Both Russia and China seek to alter the status quo of the international order, but they pose different challenges for U.S. national security, argues a new paper from RAND. Russia is a “well-armed rogue state” that represents an immediate military threat, albeit one the United States can contain. China, on the other hand, is a peer competitor. It presents a regional military challenge—and a global economic one.

Both Russia and China seek to alter the status quo of the international order, but they pose different challenges for U.S. national security, argues a new paper from RAND. Russia is a “well-armed rogue state” that represents an immediate military threat, albeit one the United States can contain. China, on the other hand, is a peer competitor. It presents a regional military challenge—and a global economic one.

The 2018 National Defense Strategy asserts “that China and Russia want to shape a world consistent with their authoritarian model.” Yet neither has an exportable ideology, RAND suggests:

- Russia backs political movements on the far right and the far left with a view to disrupting the politics of adversarial societies and, if possible, installing friendlier regimes of whatever stripe.

- China, in contrast, seems basically indifferent to the types of government of the states with which it interacts. Indeed, for many governments, one of the chief attractions of accepting Chinese aid and investment is that it comes largely free of the political conditionality that ties much Western assistance. Read more »

But does strategic competition amount to a new Cold War?

But does strategic competition amount to a new Cold War?

Perhaps, says Robert Service, the author of several major books on Russian history, including The Last of the Tsars:

Although Russia is wedded to the capitalist system, it claims to have a better idea than America about how to organise a democracy. Yet Russia and America are some way short of being locked in a comprehensive struggle for world supremacy, and the recent dip in prices for oil and gas makes Russia a less than impressive contender. Not yet a Cold War, then, but a situation of acute danger. Fingers crossed…

No, argues Vladislav Zubok, professor of international history at the LSE.

“This is a totally new ballgame…..it would be a travesty of history to regard Putin’s Russia – a regional, authoritarian and corrupt power – as waging the same battles as the Soviet Union,” he contends:

In the new situation, when global liberalism in the US and Europe is checked by internal contradictions, a major realignment may be afoot. Attempts by liberal-centrist media to portray Russia as the main enemy of the international community have failed to ignite a new Cold War because they stretch reality too far. Ironically, rightwing populists in the west now tend to see Russia as a potential ally against other challenges, from radical Islamism to powerful China.

In the new situation, when global liberalism in the US and Europe is checked by internal contradictions, a major realignment may be afoot. Attempts by liberal-centrist media to portray Russia as the main enemy of the international community have failed to ignite a new Cold War because they stretch reality too far. Ironically, rightwing populists in the west now tend to see Russia as a potential ally against other challenges, from radical Islamism to powerful China.

“Common themes from the past, such as support for democracy and alliances, remain important building blocks for bipartisan foreign policy, especially in the face of challenges from China and Russia,” adds Goldgeier, the 2018-19 Library of Congress Chair in U.S.-Russia Relations at the John W. Kluge Center. “But it is also clear that the humility induced by failed military interventions provides a huge opening to those who seek to build a more restrained American attitude toward the use of force than existed at the height of American power two decades ago.” RTWT