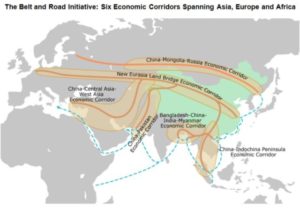

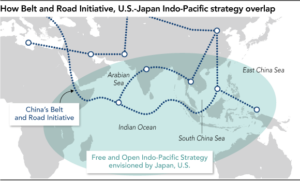

India and China are jostling for influence in Iran and Central Asia, Nikkei reports, as New Delhi’s 7,000km transport corridor cuts across Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “Neighborhood First” policy aims to counter growing Chinese influence among its South Asian neighbors, Stratfor reports. As China makes inroads into India’s closest land neighbors and charts a course to countries off its southern coast, New Delhi will have little choice but to spread its largesse around the region even more, it adds.

India and China are jostling for influence in Iran and Central Asia, Nikkei reports, as New Delhi’s 7,000km transport corridor cuts across Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “Neighborhood First” policy aims to counter growing Chinese influence among its South Asian neighbors, Stratfor reports. As China makes inroads into India’s closest land neighbors and charts a course to countries off its southern coast, New Delhi will have little choice but to spread its largesse around the region even more, it adds.

China is one of four states described as “morally reprehensible forces of instability” in the U.S. State Department’s yearly human rights report.

The U.S. fears that Beijing is showing worrying signs of regressing on reforms, Reuters reports. “Some thought leaders in China are even championing the narrative that a non-transparent, state-dominated approach to running an economy is a legitimate alternative to free and fair markets where everyone can participate,” said Kurt Tong, U.S. consul general.

The U.S. fears that Beijing is showing worrying signs of regressing on reforms, Reuters reports. “Some thought leaders in China are even championing the narrative that a non-transparent, state-dominated approach to running an economy is a legitimate alternative to free and fair markets where everyone can participate,” said Kurt Tong, U.S. consul general.

Many observers fear that China’s growing economic leverage is being translated into authoritarian political influence – what a recent National Endowment for Democracy report called ‘sharp power.’

The authoritarian influence of the Chinese Communist Party is going global, provoking concerns over its use of sharp power in the tradition of political warfare, including united front and international liaison work activities which can have a corrosive impact on democracies, argues Elsa B. Kania, an Adjunct Fellow with the Center for a New American Security.

The challenge of countering the long time horizons and whole-of-nation strategy of an authoritarian competitor is daunting, particularly at a time when faith in democracy is eroding precipitously, she adds. Yet the U.S. must not fear but rather should embrace a new era of competition and search for new paradigms that return to core values and leverage enduring advantages.

China’s push to shape other countries’ political systems underscores the need to support U.S. institutions that promote political liberalization abroad, such as the National Endowment for Democracy, the International Republican Institute, the National Democratic Institute, and the Asia Foundation, argues Elizabeth C. Economy, Senior Fellow and Director for Asia Studies at the  Council on Foreign Relations and the author of The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State.

Council on Foreign Relations and the author of The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State.

These institutions can partner with Australia, Japan, and South Korea, along with European allies, to help build the rule of law in quasi-authoritarian states and buttress nascent democracies. Legal, educational, and structural reform programs can provide a critical bulwark against Chinese efforts to project authoritarian values abroad, she writes for Foreign Affairs.

If we are talking of psychological wars, China seems to be winning without doing much, according to Kerry Brown, Director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College, London, and the author of The New Emperors, a book on the leadership of modern China. Understanding t three principle features of China’s often shadowy power allows for a better understanding of China’s influence and its likely future trajectory, he writes for the Diplomat:

If we are talking of psychological wars, China seems to be winning without doing much, according to Kerry Brown, Director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College, London, and the author of The New Emperors, a book on the leadership of modern China. Understanding t three principle features of China’s often shadowy power allows for a better understanding of China’s influence and its likely future trajectory, he writes for the Diplomat:

- First, … …no one seriously claims in modern China that the ideology of the Communist Party – Marxism-Leninism – is really believed in by anyone beyond the confines of the inner elite. China is at best a marketplace of belief systems now, with Buddhists and Christians, Daoists and Confucianists all vying with each other. …. Nowhere do we see as complete a disconnect between the belief systems of the leaders and those they lead as exists in contemporary China. …

- Second, for all the excitement and speculation about China’s military prowess and newfound hard power, we have to remember this: it might have the world’s second best funded army, and one of the largest in terms of assets and personnel, but this is a force that has not seen a single day’s proper combat since 1979 (when it fought, highly unsuccessfully, with Vietnam). …..

And finally there is the greatest illusion of all, the amorphous, grand, abstract idea of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – an idea with no common grounds for dispute resolution, no normative power, no common values beyond pragmatic engagement focused on China, and no cultural, security, or political commonality. ….The BRI could be anything, but might well be nothing. It is without boundaries, structure, or unifying content. This might be its great strength, but if so that is a spectral strength, not a real one.

And finally there is the greatest illusion of all, the amorphous, grand, abstract idea of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – an idea with no common grounds for dispute resolution, no normative power, no common values beyond pragmatic engagement focused on China, and no cultural, security, or political commonality. ….The BRI could be anything, but might well be nothing. It is without boundaries, structure, or unifying content. This might be its great strength, but if so that is a spectral strength, not a real one.

Meanwhile, for intellectuals, activists, and national minorities, Xi’s China dream increasingly resembles a twenty-first-century, high-tech, less bloody version of Mao’s China, notes Columbia University’s Andrew J. Nathan (left).

Meanwhile, for intellectuals, activists, and national minorities, Xi’s China dream increasingly resembles a twenty-first-century, high-tech, less bloody version of Mao’s China, notes Columbia University’s Andrew J. Nathan (left).

Overall, Xi is making the institutional system he inherited from Mao and Deng more responsive and efficient, But he has reversed the attempt of the period between Mao and himself to do this through rule of law, he writes for the New York Review of Books:

As Carl Minzner notes in his recent book End of an Era: How China’s Authoritarian Revival Is Undermining Its Rise, “Law is becoming less  and less relevant to China’s future.”2 Instead, Xi is creating a twenty-first-century “organizational weapon” of the kind described seventy years ago by the sociologist Philip Selznick—one that works through “disciplined and deployable political agents.”3 The agents are accountable not downward to their constituents or horizontally to legal institutions, but upward, to their superiors. The system pushes problems to the top, until they reach someone who is willing to take responsibility. Xi has emerged to shoulder this burden, and he has the personality to do so. That is why many in the party have welcomed the reversal of the Deng system, which they believe led to stagnation. RTWT

and less relevant to China’s future.”2 Instead, Xi is creating a twenty-first-century “organizational weapon” of the kind described seventy years ago by the sociologist Philip Selznick—one that works through “disciplined and deployable political agents.”3 The agents are accountable not downward to their constituents or horizontally to legal institutions, but upward, to their superiors. The system pushes problems to the top, until they reach someone who is willing to take responsibility. Xi has emerged to shoulder this burden, and he has the personality to do so. That is why many in the party have welcomed the reversal of the Deng system, which they believe led to stagnation. RTWT

China’s expanding foreign influence is an attempt to spread the illiberal norms and repressive practices that prevail domestically, observers suggest.

Hundreds of foreign not-for-profit groups in China who suspended activities after a law placing them under close state supervision went into effect last year are now returning to work as normal. But others who worked on human rights advocacy have been less successful, the FT reports:

The Economist

About 350 groups have registered offices in mainland China since the country’s international non-governmental organisation (NGO) management law became effective in January 2017……The legislation, which would in effect expel such organisations, was in line with a crackdown on human rights lawyers and feminist and labour rights activists overseen by China’s President Xi Jinping in recent years…Beijing argues the law is necessary to regulate organisations that for years have operated in a legal grey area, with many registering as businesses. Ahead of the law’s passing, state media said some groups sought to foment revolution in the country

“There was “a group of rights and advocacy organisations . . . for whom registration will be difficult or impossible”, said Mark Sidel, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, an expert on NGOs in China.

By giving Beijing the ability to block groups’ activities without explicitly banning them, the law’s registration requirement “allows plausible deniability about which groups will have to leave”, said Jessica Batke, a researcher at the Asia Society.